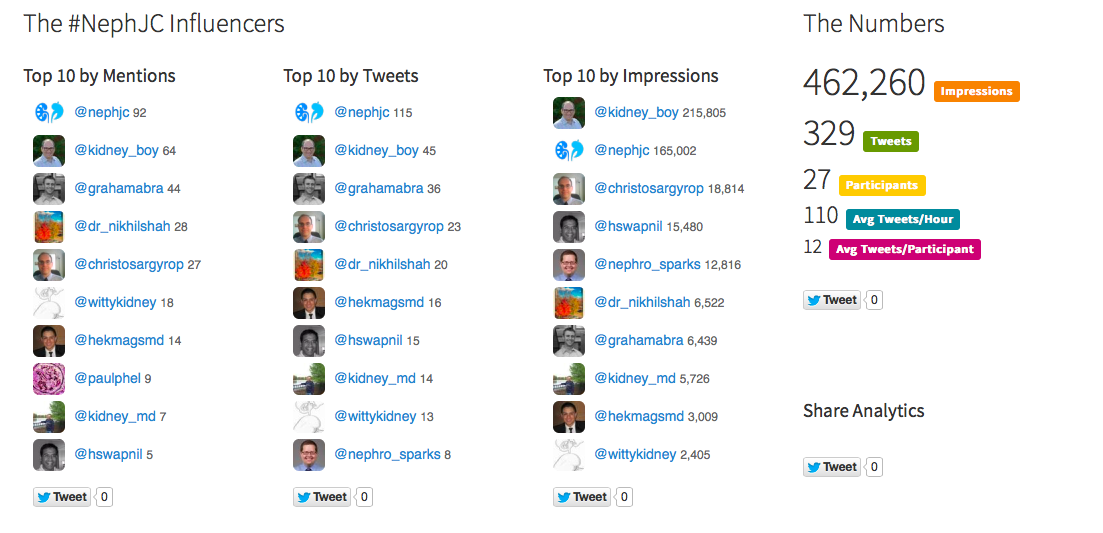

Last week, NPR ran a story on their Shots Blog based on a paper from JAMA Surgery, Quality Improvement Targets for Regional Variation in Surgical End-Stage Renal Disease Care. The story was one sided, and without balance. The truth is that irresponsible nephrologists are not the primary reason patients don't start dialysis with a fistula. Swapnil saw the post and went on a bit of a Twitter rant discussing the limitations of both the post and the article on which it was based. As is typical for our Twitter renal community, a number of other nephrologists chipped in with poignent observations and tweets. It quickly became a great academic discussion on the difficulties with fistulas.

I collected the relevant tweets and published a Storify of the entire event.

A few hours after I published the Storify I received an e-mail from Nadia Whitehead, the author of the NPR post. We did a 15 minute phone interview where I was able to provide some balance to the original article and I urged her to call Swapnil for some more feedback. She did that and posted a follow-up article a few days later.

I think this is a pretty good example of why doctors need to participate in social media in open networks like Twitter rather than behind the locked doors of private physician networks like Doximity and Sermo. We need to be engaged in the same media and networks that the public is immersed in so we can be heard and reman relevant. I think it also shows the value of curating these discussions with a tool like Storify. I played a minimal role in the discussion but she reached out to me, primarily, I imagine, because I was the author of the Storify. The Storify is what triggered the action on her part.