#NephJC Chat

Tuesday, May, 21st, 2024 at 9 pm Eastern (AEST = May 21st, 11am)

Wednesday, May 22nd, 2024, at 9 pm Indian Standard by Time and 3:30 pm GMT (AEST = May 22nd, 2am)

Kidney Int.2024 Apr;105(4S):S117-S314. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2023.10.018.

KDIGO 2024 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease

The KDIGO CKD 2024 Guidelines Part 2: CKD modification, complications and consultation initiation

Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group

PMID: 38490803

KDIGO CKD webpage

Introduction

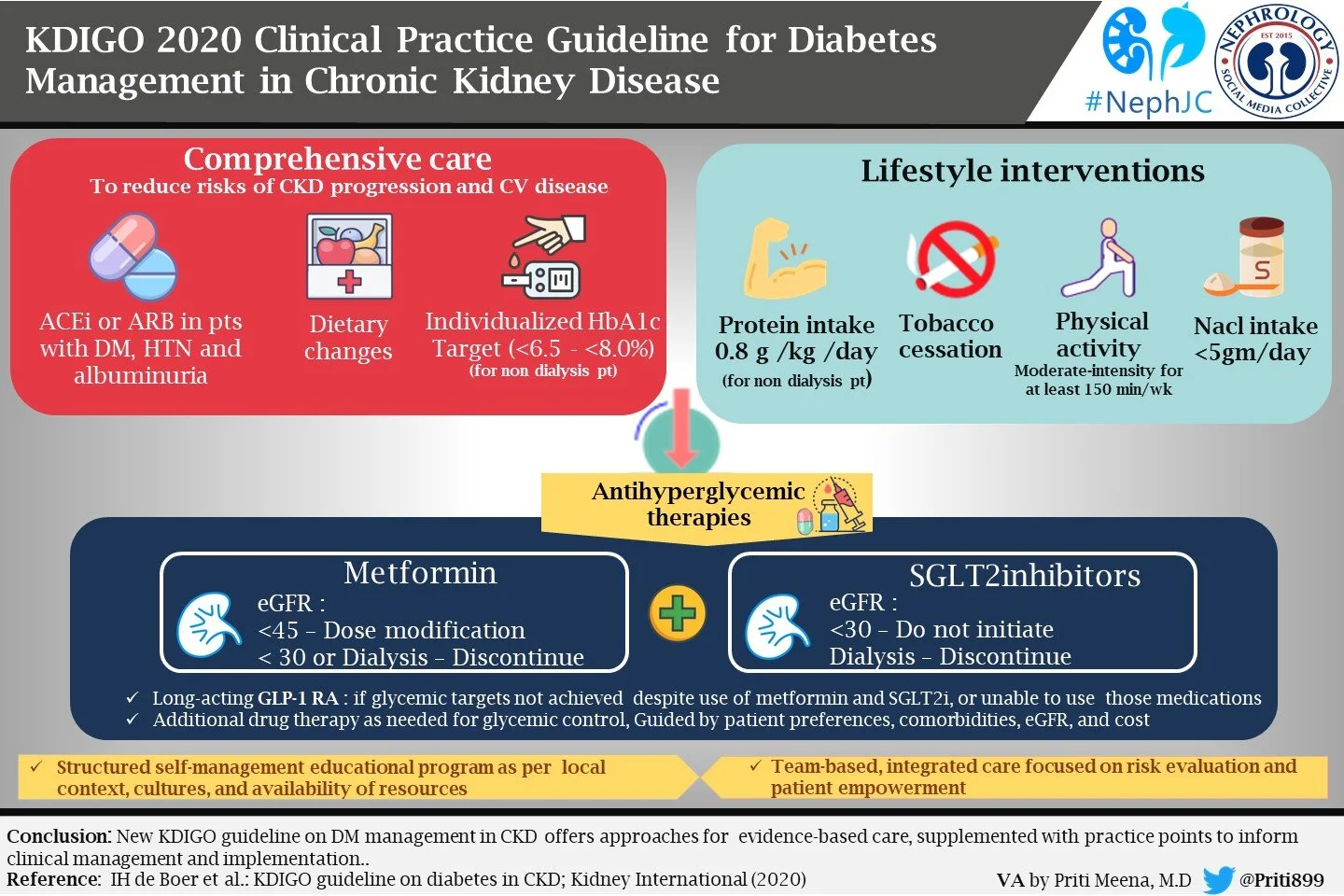

We bring to you part two of our NephJC in-depth review of the 2024 KDIGO clinical practice guideline for evaluation and management of CKD. A fortnight ago we discussed the chronic kidney disease (CKD) guidelines about the evaluation, risk management of CKD, and discussed a few research recommendations. Today we bring to you Chapter 3 on how to delay CKD progression and manage its complications. In this part we will also talk about newer therapies that have evolved over this past decade and are now considered standard. Chapter 4 focuses on medication management and drug stewardship in CKD, Chapter 5 elaborates on the optimal models of care and Chapter 6 focuses on research recommendations. Interestingly enough, for certain areas (Anemia 2012, Diabetes 2022|NephJC summary, CKD-MBD 2017) the guidelines skip by suggesting one should refer to the respective KDIGO CKD guidelines, whereas for other areas (notably BP in CKD 2021|NephJC summary) they do have some guidelines despite the recency of the comprehensive KDIGO BP guidelines.

As always the KDIGO guidelines loosely follow the GRADE framework

In addition there are several practice points, which should be interpreted as ‘consensus-based statements representing the expert judgment of the Work Group’ and are not graded. They are issued when a clinical question did not have a systematic review performed, to help readers implement the guidance from graded recommendation or for issuing “good practice statements” when the alternative is considered to be absurd. Users should consider the practice point as expert guidance and use it as they see fit to inform the care of patients. Although these statements are developed based on a different methodology, they should not be seen as “less important” or a “downgrade” from graded recommendations.

Overall the chapters include 42 recommendations and 141 practice points.

Chapter 3: Delaying CKD Progression and managing its complications

Comprehensive treatment strategy

“An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure!”

Goal (as outlined in the first practice point of this section): Treat people with CKD in order to reduce the risks of progression of CKD and its associated complications with a comprehensive treatment strategy

What lifestyle modifications are recommended for patients with CKD?

1. Lifestyle

Practice points emphasize the importance of apparently simple yet possibly effective lifestyle interventions like physical activity, an optimal BMI and saying no to tobacco.

2. Physical activity and optimum weight

KDIGO says that while endorsing physical activity, one must consider age, ethnicity, comorbidities and access to resources. In people with increased risk of falls, practitioners should provide guidance about the intensity and type of exercise. Obese people with CKD should be encouraged to lose weight (easier said than done, until the advent of GLP1RAs). The recommendations extend to children with CKD, who should perform physical activity aiming for WHO advised levels (i.e.≥60 minutes daily for 5-17 year olds and ≥180 min for 1-5 year olds). There is an emphasis on limiting screen time and encouraging moderate to vigorous physical activity in kids. Except for the recommendation regarding physical activity (1D), the rest of all lifestyle modifications are given as practice points.

3. Diet

In a Practice Point, the authors emphasize healthy, diverse diets, with avoidance of ultra-processed foods and preference for plant-based proteins over animal-based proteins. The lack of high quality data to support plant-based diets allows KDIGO to slip this in as a practice point. Involvement of renal dietitians is encouraged for individualized management of sodium, phosphorus, potassium, and protein intake

Addressing the age-old question, KDIGO sticks to 0.8 mg/kg/day protein intake in adults with CKD G3–G5 (2C) which is similar to the recommended daily allowance of protein in the general population. Whether high-protein intake causes or accelerates preexisting kidney disease is a long-standing debate in nephrology (Obied W et al, Kidney360, 2022). The data supporting a low protein diet were largely collected before widespread adoption of RASi and entirely before the data on flozination and glipination, all of which are actually effective (with RCT data), unlike dietary protein restriction. The guideline asks us to not exceed protein intake >1.3 g/kg/d in CKD at risk of progression (PP 3.3.2). Despite the poor quality data, the KDIGO workgroup slips in another practice point to consider a very low–protein diet (0.3 - 0.4 g/kg body weight/d) with ketoacid analogs (up to 0.6 g/kg body weight/d) in adults at risk of kidney failure, but not in metabolically unstable people with CKD. Indeed, in older adults with frailty and sarcopenia, one should consider higher protein and calorie dietary targets. Also, it emphasizes not restricting protein intake in children with CKD, targeting protein and energy intake at the upper end of the normal range for healthy children, to sustain optimal growth.

4. Sodium intake

KDIGO calls for stringent salt restriction with <2 g of sodium per day in people with CKD (2C). It asks us to follow age-based Recommended Daily Intake when counseling about sodium intake for children with CKD who have systolic and/or diastolic blood pressure >90th percentile for age, sex, and height. It is prudent to identify salt-losing nephropathy and not restrict salt there. In the SSaSS trial (Neal et al, NEJM 2022|NephJC summary) we learned about the benefits of systematically replacing sodium with potassium on decreasing stroke, MACE and death in an older, rural Chinese cohort. It will likely take changes at the industrialized food processing level to significantly impact people’s daily salt consumption in the western world (Shimamura et al, Kidney Med 2022).

What are the targets for blood pressure in adults and children?

Which drugs can be used for delaying CKD progression? (RASi, SGLT2i, MRA, GLP-1 RA? ..hooray!)

1. Renin-angiotensin system inhibitors

This recommendation, specifically in non-diabetic but albuminuric CKD, is strong according to grade 1B, based on 3 moderate-quality RCTs which showed tremendous benefit in terms of renoprotection and CV benefits in CKD patients (REIN trial, stratum 2 & 1 The GISEN group, Lancet 1997; Ruggenenti et al, Lancet 1999; AIPRI trial Maschio et al, NEJM 1996; Hou et al, NEJM 2006).

Figure 6 from KDIGO BP guidelines

Conversely, in patients without diabetes or moderate albuminuria (A2, 3-29 mg/mmol or 30-299 mg/g) the recommendation is weak (2C), as we have limited evidence from RCTs of sufficient duration to look at renoprotection. The basis of this recommendation was the HOPE study, in which a subgroup analysis of those with CKD and normal-to-moderately increased albuminuria (creatinine clearance <65 ml/min; n=3394; mean follow-up 4.5 years) showed that ACEi, versus placebo, reduced the risk for all-cause mortality by 20%, MI by 26% and stroke by 31% (Slight P et al, J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst 2000).

Finally, in patients with diabetes and moderate to severe albuminuria (A2-A3), there is a strong recommendation to start RASi (1B). This recommendation is based on evidence from RCTs of sufficient duration on renoprotection in diabetes and CKD such as IDNT (Lewis et al, NEJM 2001) & RENAAL (Brenner et al, NEJM 2001). It places a relatively higher value on preventing long-term progression of CKD and a relatively lower value on the risks of AKI or hyperkalemia.

This recommendation places a higher value on preventing harm from hyperkalemia and AKI than on lowering proteinuria. As we know, dual RAS blockade with an ACEi, ARB, or DRI does not provide any long-term CV or kidney benefit despite lowering proteinuria but does confer an increased risk of hyperkalemia and AKI as evidenced by the ONTARGET (Yusuf et al, NEJM 2008) and VA-NEPHRON-D (Fried et al, NEJM 2013) trials.

Practice Point 3.6.1: RASi (ACEi or ARB) should be administered using the highest approved dose that is tolerated to achieve the benefits described because the proven benefits were achieved in trials using these doses.

The only problem is that there is no consensus on the highest approved dose of RASi. Dosing varies across nations and their regulatory bodies. The table provided by KDIGO on dosing, especially in renal impairment, seems very outdated and would result in underdosing RASi. Fortunately, patients not tolerating a high dose can still be put on a smaller dose for renoprotection!

Figure 3. Dosage recommendations for RAS inhibitors. KDIGO Diabetes in CKD guidelines 2022

Practice Point 3.6.6: Consider starting people with CKD with normal to mildly increased albuminuria (A1) on RASi for specific indications (e.g. to treat hypertension or HFrEF).

This practice point allows one to sneak in RASi even in the absence of DM or albuminuria, and is otherwise quite reasonable. One wonders why it is only a practice point in the presence of RCT data supporting RASi in reducing CV outcomes?

Practice Point 3.6.3: Hyperkalemia associated with use of RASi can often be managed by measures to reduce the serum potassium levels rather than decreasing the dose or stopping RASi.

This can be done in practice by using diuretics or using potassium binders, or trying dietary potassium restriction. Newer potassium-lowering agents appear to be better tolerated for long-term use with RASi.

Practice Point 3.6.5: Consider reducing the dose or discontinuing ACEi or ARB in the setting of either symptomatic hypotension or uncontrolled hyperkalemia despite medical treatment, or to reduce uremic symptoms while treating kidney failure (eGFR < 15 ml/min/1.73m2).

Practice Point 3.6.7: Continue ACEi or ARB in people with CKD even when eGFR falls below 30 ml/min/1.73m2.

The advice on reducing or stopping RASi (described above) seems like common sense (except the one on reducing uremic symptoms which seems of doubtful provenance). On the other hand, curiously, the continuing RASi advice below eGFR< 30 ml/min/1.73m2 comes across only as a practice point despite strong RCT evidence showing futility of discontinuation in terms of GFR decline (the STOP-ACEi trial Bhandari S, et al. NEJM 2022, NEJM Summary) as well as epidemiological data supporting cardiovascular benefit of continuation (Fu E et al, JASN 2021).

Practice Point: Continue ACEi or ARB therapy unless serum creatinine rises by more than 30% within 4 weeks following initiation of treatment or an increase in dose.

Why not 20% or 40%, what is the basis for this sacrosanct value of 30 percent, do we have any good data? Obviously, this recommendation is not written in stone and is left to the physician to individualize a plan. See this study (Schmidt et al, BMJ 2017, NephJC summary) for more details around this topic.

2. Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT2i)

Flozins are a breakthrough therapy for CKD as these have remarkable ability to retard kidney disease progression, CV mortality, and heart failure ( no surprise for NephJC readers!). The KDIGO recommendation for flozination in CKD is consistent with, but expands on, Recommendation 1.3.1 from the KDIGO 2022 Diabetes guidelines to include non-diabetic CKD because of the gigantic trial data that has been amassed. These started with the CV safety trials in DM (EMPAREG, followed by CANVAS, DECLARE, VERTISCV and SCORED) which suggested a renal benefit. This was confirmed in the renal specific trials initially in Diabetes (CREDENCE) quickly followed by expansion by trials including DM and proteinuric CKD as well (DAPACKD) and lastly DM and proteinuric as well as non-proteinuric CKD (EMPAKIDNEY). In parallel, there have been several heart failure trials (typically having a mix of DM and non-DM patients) which also have included renal secondary endpoints. The consistent benefit of flozination in CKD has been summarized nicely in the SMART-C (Staplin et al, Lancet 2022) (collaborative meta-analysis of 13 trials with just over 90,000 randomized participants and showed that in comparison with placebo, participants in SGLT2i experienced a 37% reduction in the risk of kidney disease progression and a 23% reduction in the risk of AKI irrespective of diabetes status. It also reported that compared with placebo, allocation to an SGLT2i reduced the risk of the composite of cardiovascular death or hospitalization for heart failure by 23% irrespective of diabetes status.

Figure 22. KDIGO CKD 2024 guidelines

On this basis, the non-DM flozination recommendations are

A 1A recommendation if there is albuminuria (ACR > 200 mg/g or 20 mg/mmol) OR heart failure irrespective of albuminuria

A 1B recommendation if eGFR 20 - 45 ml/min/1.73 m2 AND albuminuria < 200 mg/g or 20 mg/mmol

This latter, slightly weaker recommendation, is reasonable as only EMPAKIDNEY included non-albuminuric patients, and the outcome that reported benefit in that subgroup was on the basis of GFR slope analysis.

The practice points suggest that once we start SGLT2i, it is reasonable to continue an SGLT2i even if the eGFR falls below 20 ml/min per 1.73 m2, unless it is not tolerated or KRT is initiated. Also, it is reasonable to withhold SGLT2i during times of prolonged fasting, surgery, or critical medical illness (greater risk for ketosis). SGLT2i initiation or use does not necessitate alteration of frequency of CKD monitoring and the reversible decrease in eGFR on initiation is generally not an indication to discontinue therapy.

3. Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRA)

The recommendation is based upon the results of the FIDELIO-DKD (Bakris et al, NEJM 2020, NephJC summary), FIGARO-DKD (Pitt et al, NEJM 2021) trials and their pooled analysis FIDELITY (Agarwal et al, EHJ 2022) which reported the efficacy of the nsMRA (finerenone) in decreasing CV risk in people with CKD and T2D (HR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.78–0.95) as well as the composite kidney outcome (HR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.67-0.88; P = 0.0002). This is one of those curious 2A guidelines, the A reflecting that the certainty of the evidence base is pretty good (in this case from two RCTs) but the 2 reflecting that not all patients would opt for this and that a policy recommendation around this will require substantial debate. Hence this recommendation is accompanied by several practice points to help provide more context.

Practice Point 3.8.1: Nonsteroidal MRA are most appropriate for adults with T2D who are at high risk of CKD progression and cardiovascular events, as demonstrated by persistent albuminuria despite other standard-of-care therapies.

Practice Point 3.8.2: A nonsteroidal MRA may be added to a RASi and an SGLT2i for treatment of T2D and CKD in adults.

Practice Point 3.8.3: To mitigate risk of hyperkalemia, select people with consistently normal serum potassium concentration and monitor serum potassium regularly after initiation of a nonsteroidal MRA

These three points emphasize the ‘2’ aspect of which patients are appropriate for nsMRA and how nsMRAs could be deployed.

Practice Point 3.8.4: The choice of a nonsteroidal MRA should prioritize agents with documented kidney or cardiovascular benefits.

This is interesting, and seems to suggest that the guideline only applies to finerenone, without spelling that out explicitly.

Practice Point 3.8.5: A steroidal MRA may be used for treatment of heart failure, hyperaldosteronism, or refractory hypertension, but may cause hyperkalemia or a reversible decline in glomerular filtration, particularly among people with a low GFR.

This last PP gives some wiggle room to those who would want to use cheap old spironolactone (or eplerenone) given that we do have RCT data to suggest its use in heart failure (e.g. RALES, Pitt et al, NEJM 1999), and resistant hypertension (PATHWAY-2 Williams et al Lancet 2015 |NephJC summary).

Figure 27. Finerenone vs placebo on kidney and CV outcomes. KDIGO CKD guidelines

4. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RA) - currently recommended for glycemic control, but we know what’s coming up,right?

Practice Point: Prioritize agents with documented cardiovascular benefits

This is what the workgroup calls as a ‘highlight; from the DM guideline (see NephJC summary) they wish to point out. Again, the CV benefit PP seems to point in the direction of semaglutide. This recommendation will likely need to move up a notch once the FLOW trial (Protocol paper at Rossing et al, NDT 2023) results are published later this week.

What are the recommendations for the treatment of CKD complications?

“The good physician treats the disease; the great physician treats the patient who has the disease.”— William Osler

1. Metabolic acidosis

Practice Point 3.10.1: In people with CKD, consider use of pharmacological treatment with or without dietary intervention to prevent development of acidosis with potential clinical implications (e.g., serum bicarbonate <18 mmol/l in adults).

Practice Point 3.10.2: Monitor treatment for metabolic acidosis to ensure it does not result in serum bicarbonate concentrations exceeding the upper limit of normal and does not adversely affect BP control, serum potassium, or fluid status.

This is a big pivot from the 2B recommendation in the 2012 (Oral bicarbonate supplementation in those with levels < 22 mmol/L to maintain serum bicarbonate within the normal range). That one was based on some implausible effect sizes from initial studies (e.g. de Brito-Ashurst et al, JASN 2009 and Biagio R. di lorio et al, Journal of Nephrology 2019). Subsequent trials (eg BICARB study, BMC Medicine 2020; VALOR-CKD, Tangri et al, JASN 2024) and some sober meta-analysis (Hultin et al, KI Reports 2021) have cast a sufficient shadow of doubt on the data to degrade this to a practice point of suggesting bicarb treatment only when it’s lower than 18, with warnings about possible harm. In the transplant setting as well, we have RCT data to show the futility of this approach (Mohebbi N et al, Lancet 2023|NephJC summary).

2. Hyperkalemia

Interestingly for a topic that we care about so much, there are no recommendations, but a bunch of practice points. Firstly, the workgroup tells you not to take a serum potassium number at face value, as discussed below.

For management, we have had trials and new molecules, but they don’t make it to a recommendation (perhaps because the trial outcomes are lowering the K number, and not a clinical outcome; though one could argue lowering the K number is often a relevant outcome!). The practice point however stresses the value of being aware of local availability and formulary restrictions for these agents.

3. CKD-Mineral Bone Disorder (CKD-MBD)

The Work Group merely highlights the KDIGO 2017 Clinical Practice Guideline Update for the Diagnosis, Evaluation, Prevention, and Treatment of Chronic Kidney Disease–Mineral and Bone Disorder (CKD-MBD).

But there is much to disagree with in the 2017 guidelines, which are sadly not discussed/revamped by the workgroup. In 2017, the workgroup still recommended pushing PO4 towards normal range (2C) and a preference for non-calcium based phosphate binders (2B). We have discussed on NephJC before about the poor evidence base behind these recommendations (e.g. LANDMARK trial, Ogata et al, JAMA 2021, NephJC summary, NephJC rant, AJKD blog post, NephTrials blog). Meanwhile, the FDA keeps approving newer phosphate binders (e.g. sucroferric hydroxide, tenapanor) despite evidence of clinical benefit beyond lowering the phosphate number. The lack of KDIGO leadership in making some sensible recommendations here is a travesty.

4.Hyperuricemia

The goal here is to avoid acute gout symptoms and prevent long-term complications of recurrent gout, and not for retarding disease progression or modifying the cardiovascular outcomes or all cause mortality in patients with CKD. The overall evidence of treating hyperuricemia for delaying CKD progression is very low as evidenced by the CKD FIX (Badve SV et al, NEJM 2020) and PERL (Afkarian M et al, Diabetes Care 2019) studies (also see NephJC summary). The major criticism of these studies was that they did not specifically address hyperuricemia (the majority of the subjects had normal uric acid levels hence the 2D level of this recommendation).

Table 30 RCTs in treatment of asymptomatic hyperuricemia in CKD. KDIGO CKD guidelines 2024.

What treatment can be given for Cardiovascular disease (CVD) and what specific interventions may be given to modify CVD risk?

In CKD, the same principles should be used to manage atherosclerotic risk as in the general population. Also, the level of care for CVD offered to people with CKD should not be prejudiced by their GFR. Prevention of ASCVD should include pharmaceutical, dietary, and lifestyle intervention, targeting traditional factors like BP, dyslipidemias and CKD-MBD.

1. Management of hyperlipidemia

Almost everyone with CKD deserves a statin - with differing grades based on the underlying evidence. In the associated practice points, the workgroup suggests using validated risk tools (they mention SCORE and AHA PREVENT as the only validated ones) to assess CV risk while initiating statins and to consider other means of targeting lipids such as PCSK-9 inhibitors. We again see the workgroup’s soft spot for plant based diets creep in here.

2. Use of antiplatelet therapy

Aspirin has fallen out of favor as primary prevention due to higher risk of GI bleeding particularly in an elderly population. Patients with CKD, and especially ESKD have risk factors for both bleeding and thrombosis. Again, similar to lipid lowering, this recommendation stands for patients both with CKD and without CKD.

3. CKD and atrial fibrillation

There remains a high prevalence of AF in CKD (16%-21% in non-dialysis CKD). As per studies, patients with CKD G3/A1 had an adjusted risk of AF of 1.2–1.5, increasing to an adjusted risk of 4.2 by CKD stages G5/A3. Risk increases with age and AF remains a risk factor for thromboembolic stroke, heart failure, increased risk of death, hospitalization, vascular dementia, depression, and reduced QoL. AF can be asymptomatic and symptoms are not a prerequisite for complications. Opportunistic pulse-based screening followed by a 12 lead ECG, if an irregularly irregular pulse is found, is used to diagnose AF in CKD. If a 12 lead ECG is non-diagnostic, a patient-activated or wearable device or Holter monitoring should be considered. AF carries an annual risk of stroke of nearly 3 times higher in CKD patients and 5 times higher in kidney failure patients versus those with AF without CKD.

Figure 40. Strategies for diagnosis and management of AF in CKD. KDIGO CKD Guidelines 2024

The recommendation places a high value on NOAC not only because of their simpler pharmacokinetic profile, dosing, and lack of need of INR monitoring, but also due to improved efficacy with a similar safety profile. In studies, the risk of stroke or systemic embolic events decreased by 19% with NOACs versus warfarin (RR 0.81; 95% CI, 0.73–0.91). This resulted largely from reduced risk of hemorrhagic strokes (RR 0.49; 95% CI, 0.38–0.64) with consistent advantage in CKD. NOACs are cost-effective for stroke prevention in AF and may even be cost-saving in CKD. We should take into account that data in CKD G5, on dialysis, were limited to observational studies and thus these should be used with caution.

Figure 42. VKA vs NOACs bleeding risk in CKD. KDIGO CKD guidelines 2024

Practice Point 3.16.2: NOAC: Adjust dose for GFR. Use with caution (as these are understudied in these groups of patients)

Figure 44. Discontinuation advice for NOACs in periprocedure period. KDIGO CKD guidelines 2024

Practice Point 3.16.3: How long to discontinue NOAC before elective procedures.Consider procedural bleeding risk, NOAC prescribed & GFR.

Figure 43. Therapeutic anticoagulation dosing in CKD by GFR. KDIGO CKD Guidelines 2024

Chapter 4: Medical Management and Drug Stewardship in CKD

How should medications be monitored and prescribed in patients with CKD?

‘’CKD Medications, Guarded with Precision’’

The KDIGO guidelines provide recommendations for medication dosing in CKD in chapter 4. This chapter discusses key concepts of drug stewardship in people with CKD, and has no recommendations, but 18 practice points.

4.1 Medication choices and monitoring for safety

The practice points here are mostly common sense guidance around nephrotoxicity, GFR monitoring when using potentially nephrotoxic medications, herbal and OTC medications and use of medications in child bearing.

Practice Point 4.1.1: People with CKD may be more susceptible to the nephrotoxic effects of medications. When prescribing such medications to people with CKD, always consider the benefits versus potential harms.

While this may seem like pablum, in table 31, the workgroup makes some interesting suggestions (see linezolid or daptomycin in place of vancomycin, H2RAs in place of PPIs and more)

Practice Point 4.1.2: Monitor eGFR, electrolytes, and therapeutic medication levels, when indicated, in people with CKD receiving medications with narrow therapeutic windows, potential adverse effects, or nephrotoxicity, both in outpatient practice and in hospital settings.

Practice Point 4.1.3: Review and limit the use of over-the-counter medicines and dietary or herbal remedies that may be harmful for people with CKD.

The workgroup avoids a blanket avoidance of herbal supplements, but provides details of commonly used and known harmful supplements in this nice figure.

Figure 45: Selected herbal remedies and dietary supplements with evidence of potential nephrotoxicity, grouped by the continent from from where the reports first came. KDIGO CKD 2024 guidelines

Practice Point 4.1.4: When prescribing medications to people with CKD who are of child-bearing potential, always review teratogenicity potential and provide regular reproductive and contraceptive counseling in accordance with the values and preferences of the person with CKD.

Again these are common sense guidance. Though not a practice point, the workgroup specifically discusses sex differences in medication safety and efficacy as being understudied. For example, sex differences in body weight and composition as well as physiological functions (lower RAAS activity in women) may impact drug metabolism and response. Because drug dosages are often universal, women are more likely to consume higher doses in relation to their body weight. Though evidence is lacking to make even any practice point suggestions, this is definitely an area befitting the ‘more research is needed cliche’.

4.2 Dose adjustment by level of GFR

Practice Point 4.2.1: Consider GFR when dosing medications cleared by the kidneys.

No surprises here.

Practice Point 4.2.2: For most people and clinical settings, validated eGFR equations using SCr are appropriate for drug dosing.

This is a shot against the commonly used Cockroft-Gault creatinine clearance for drug dosing (also see FDA guidance [PDF link] confirming this).

Practice Point 4.2.3: Where more accuracy is required for drug-related decision-making (e.g., dosing due to narrow therapeutic or toxic range), drug toxicity, or clinical situations where eGFRcr estimates may be unreliable, use of equations that combine both creatinine and cystatin C, or measured GFR may be indicated.

See the NephJC coverage of this area for more details.

Practice Point 4.2.4: In people with extremes of body weight, eGFR non indexed for body surface area (BSA) may be indicated, especially for medications with a narrow therapeutic range or requiring a minimum concentration to be effective.

GFR is indexed to 1.73m2 which was apparently the mean BSA of adults in the US in 1920. This is no longer true (it’s closer to 1.9 m2) and in particular is problematic when the actual body size of an individual is quite different from 1.73 where there is a risk of over/underdosing. In these situations, the practice point suggests ‘de-indexing’ or adjusting for a patient's BSA. using the simple formula: eGFR (adjBSA) which will be in ml/min = eGFR *(actual BSA/1.73).

Practice Point 4.2.5: Consider and adapt drug dosing in people where GFR, non-GFR determinants of the filtration markers, or volume of distribution are not in a steady state.

When things are not in a steady state, the workgroup suggests adapting dosing (though sadly does not give a shout out to innovative ways to do this such as kinetic GFR (Chen, JASN 2013) . In cancer patients with CKD, measured GFR may be preferred to guide the drug dosing for some anticancer drugs like carboplatin, cisplatin, and methotrexate.

4.3 Polypharmacy

Practice Point 4.3.1: Perform thorough medication review periodically and at transitions of care to assess adherence, continued indication, and potential drug interactions because people with CKD often have complex medication regimens and are seen by multiple specialists.

No surprises here too. One should discontinue medications that are no longer indicated and may contribute to kidney injury (eg PPIs, NSAIDs). The guidelines also emphasize the importance of rational medication use and minimizing the risk of medication related adverse effects to avoid inadvertently contributing to the ‘’prescribing cascade’’.

Practice Point 4.3.2: If medications are discontinued during an acute illness, communicate a clear plan of when to restart the discontinued medications to the affected person and healthcare providers, and ensure documentation in the medical record.

Sick day rules are popular in the setting of acute, dehydrating illnesses, but the workgroup emphasizes the lack of data to support them (Doerfler et al, CJASN 2019 and Fink et al, Kidney Med 2022). The “SADMANS’’ acronym is a helpful mnemonic to remember the drugs that should be temporarily stopped during sick days (sulfonylureas, ACEi, diuretics/direct renin inhibitors, metformin, ARBs, NSAIDs, and SGLT2i). But the guideline practice point categorically does not endorse sick day rules, and only emphasizes the last step - to make sure the withheld medications are restarted. Steps for sick day rules implementation are illustrated in the infographic.

Practice Point 4.3.3: Consider planned discontinuation of medications (such as metformin, ACEi, ARBs, and SGLT2i) in the 48–72 hours prior to elective surgery or during the acute management of adverse effects as a precautionary measure to prevent complications. However, note that failure to restart these medications after the event or procedure may lead to unintentional harm (see Practice Point 4.3.2).

This is an interesting practice point with little data to support it but expert opinions - and is even somewhat outdated and inaccurate. The SPACE trial (Ackland et al, EHJ 2024 | NephJC summary) clearly demonstrated no benefit from withholding RASi perioperatively - and actual harm from doing so (more hypertensive episodes).

Note that the practice point does NOT endorse sick day rules and only emphasizes the need to restart medications if someone follows sick day rules.

4.4 Imaging Studies

Practice Point 4.4.1: Consider the indication for imaging studies in accordance with general population indications. Risks and benefits of imaging studies should be determined on an individual basis in the context of their CKD.

Kind of a cop-out; this would have been a useful place to say one should not avoid renalism and CKD patients should receive contrast if clinically indicated. Lost opportunity! The risk factor table 33 is a hodge podge (which nephrotoxic medications?) and not very useful.

Practice Point 4.4.1.1: Assess the risk for AKI in people with CKD receiving intra-arterial contrast for cardiac procedures using validated tools.

Which validated tools? The workgroup does not provide any. We recommend the NCDR risk score (Tsai et al, JAHA 2014).

Practice Point 4.4.1.2: The intravenous administration of radiocontrast media can be managed in accordance with consensus statements from the radiology societies in people with AKI or GFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (CKD G3a–G5) undergoing elective investigation.

They do not tell you which ones, presumably the ACR-NKF guidelines (Davenport et al, Kidney Med 2020; or possibly CAR McDonald et al, CanJKDH 2022). The discussion is mostly reasonable. A nice point made is in people with eGFR >30 and without evidence of AKI, metformin need not be stopped and there is no need for testing to evaluate GFR afterward. Bravo, shout it from the rooftops! To counter that, there is a weaselly statement to consider withholding RASi which flies in the face of trial data (e.g. Rosenstock et al, IUN 2008).

Practice Point 4.4.2.1: For people with GFR <30 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (CKD G4–G5) who require gadolinium-containing contrast media, preferentially offer them American College of Radiology group II and III gadolinium-based contrast agents.

Again reasonable. See NephJC discussion of topic here.

Chapter 5: Optimal models of care

This chapter has no recommendations but 23 practice points.

‘’Guiding Care, Empowering Lives’’-Optimal Models of Care

5.1 When should a referral to a kidney specialist and KRT be considered?

The guidelines recommend referral of adults with CKD to specialist kidney care services in several scenarios like advanced CKD, rapidly declining kidney function, presence of significant albuminuria, refractory hypertension and patients requiring renal replacement therapy. For CKD, the workgroup suggests a threshold of 3-5% for a validated risk tool (presumably the KFRE; Tangri et al, JAMA 2011); or an absolute GFR < 30, or a sustained fall of 20-30% or more in GFR in those on ‘hemodynamically active therapies’ (presumably RAASi or flozins?). The guidelines also emphasize the importance of timely early referral to a nephrologist, suggesting that early referral can offer several benefits over late referral.

For children and adolescents, the guidelines have a special practice point to advocate early referral to specialist kidney care services with a broader set of criteria (eg recurrent UTI, persistent hematuria, any hypertension etc) that will ensure optimal management of pediatric complications of CKD (including growth restriction) and promote access to preemptive transplantation.

5.2 How should we manage symptoms in CKD?

Given the lack of evidence, there are no recommendations, but a few useful practice points and discussion. CKD confers a high burden of uremic symptoms that may be under-recognized, underdiagnosed, and undertreated. The KDIGO guidelines highlight fatigue as the most prevalent CKD symptom, while sexual dysfunction as the most severe symptom. Health care providers should be attentive to both physical and psychological aspects when managing patients with CKD and ask patients about uremic symptoms at each consultation using a standardized validated uremic symptoms tool. The guidelines also emphasize a comprehensive approach and evidence-informed (since there are no evidence-based options) management strategies to support people to live well with CKD. The CKD symptoms and management strategies are shown in the infographic.

Malnutrition is a significant concern in patients with CKD and healthcare providers are advised to use validated assessment tools such as 7-Point Subjective Global Assessment (SGA) or the Malnutrition-Inflammation Score (MIS). Nutritional assessment and intervention should be undertaken twice annually for people with CKD who present with frailty, age >65 years, weight loss, poor growth (pediatrics), poor appetite, and all people with CKD G4 and G5. CKD patients with malnutrition should receive Medical Nutrition therapy (MNT) under the supervision of renal dietitians or accredited nutrition providers if not available.

5.3 Team-based integrated care

In the context of CKD, the chronic care model (CCM) emphasizes the importance of a multidisciplinary approach, and integrated care, to effectively manage the disease and improve patient outcomes. The specific components for CKD models of care include a navigation system that leads to timely referral, education programs, surveillance protocols, patient management and lastly three-way communication between people with CKD, their multidisciplinary specialist care team and their primary care providers. KDIGO guidelines stress implementation of education programs that play a crucial role in empowering people with CKD to actively participate in their care and make informed decisions about their health. Educational material should be written and explained clearly with plain language and cover 3 main subject areas- knowledge about CKD, knowledge about treatment to slow progression and complications of CKD, and knowledge about the kidney failure management options. Telehealth can be incorporated to augment patient care in CKD and offers a valuable platform for remote monitoring, providing education and improving delivery of care.

Pediatric considerations

This aspect receives special attention with 3 practice points each for pediatric and adult providers. The transition of adolescents with CKD from pediatric to adult care is an important aspect of their healthcare management and the transition process should start at 11–14 years of age. By implementing a structured transfer process including preparation of adolescents, transition summary and transfer of care, healthcare providers can help adolescents with CKD navigate the complexities of transitioning to adult care successfully.

5.4 When should we initiate dialysis?

Practice Point 5.4.1: Initiate dialysis based on a composite assessment of a person’s symptoms, signs, QoL, preferences, level of GFR, and laboratory abnormalities.

Practice Point 5.4.2: Initiate dialysis if the presence of one or more of the following situations is evident (Table 41). This often but not invariably occurs in the GFR range between 5 and 10 ml/min per 1.73 m2.

The interesting aspect is that the workgroup cites the IDEAL trial (Cooper et al, NEJM 2010) which reported no benefit of starting early, and yet this remains a practice point and not a recommendation? They refer to recent studies with ‘advanced statistical techniques’ (e.g. Fu et al, NEJM 2021|NephJC summary) which may have resulted in downgrading this potential recommendation to a practice point.

Practice Point 5.4.3: Consider planning for preemptive kidney transplantation and/or dialysis access in adults when the GFR is <15–20 ml/min per 1.73 m2 or risk of KRT is >40% over 2 years.

This again seems like sensible guidance.

In children, in addition to the adult indications for dialysis, poor growth refractory to optimized nutrition, growth hormone, and medical management is also an indication for initiating KRT.

5.5 Supportive care and comprehensive conservative management

Informing people with CKD about conservative care and the option to forego dialysis in favor of conservative kidney management is an essential aspect of patient-centered care. Healthcare providers should engage in open and honest discussions with patients about their treatment options. Advanced care planning (ACP) is a process under the comprehensive conservative care umbrella that involves understanding, communication, and discussion between a person with CKD, the family, caregiver, and healthcare providers for the purpose of clarifying preferences for end-of-life care.

Conclusion

Guidelines in general, and guidance from KDIGO specifically, is meant to be a series of points for discussion and debate based upon the currently available best evidence. There are still many areas of nephrology and CKD care that require more evidence and better studies so that we can give patients living with CKD every opportunity to live longer, healthier lives. Newer therapeutics gain a foothold after FDA approval but leave clinicians wondering about the best timing and use of limited resources while increasing pill burden and cost. Ultimately, just like ESKD care, CKD care is moving more toward individualization with integration of the patients’ voices as well. This model can benefit both physicians and patients when clear goals of treatment are defined early in the disease process. The KDIGO workgroups continue to integrate a plethora of information and we can all appreciate their thoughtful guidance.

Summary by

Kavita Vishwakarma,

Consultant Nephrologist,

Bhaktivedanta hospital & research institute,

Mumbai, India

Jasmine Sethi

Assistant Professor Nephrology

PGIMER, Chandigarh, India

Infographics created by

Jasmine Sethi, Elba Medina, Medhavi Gautam, Vamsidhar Veeranki, StephanieTorres, Cristina Popa

Summary reviewed by

Brian Rifkin, Sayali Thakare, Cristina Popa, Swapnil Hiremath

Visual Abstracts reviewed by

Anand Chellappan, PS Vali, Divya Bajpai, Priti Meena, Cristina Popa

Header Image created by AI, based on prompts by Evan Zeitler