#NephJC Chat

Tuesday Nov 29th 2022 9 pm EDT

Wednesday Nov 30th 2022 9 pm IST

N Engl J Med 2022 Nov 3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2210639. Online ahead of print.

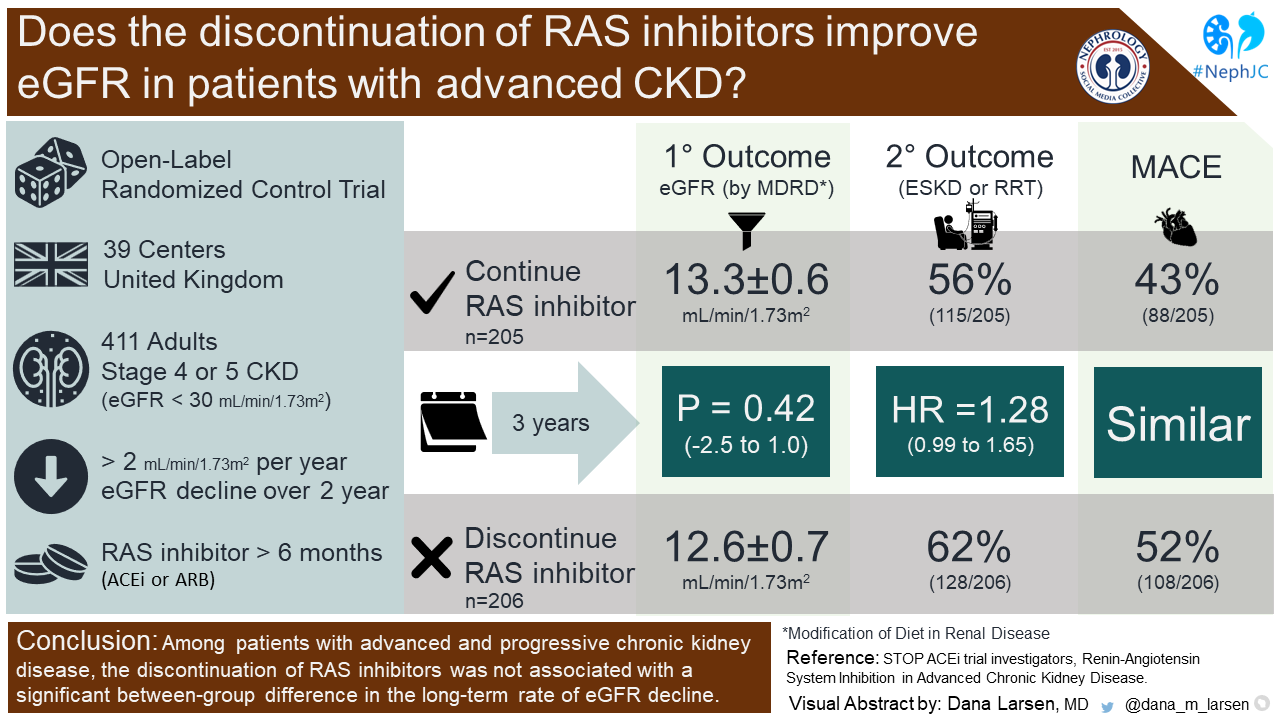

Renin-Angiotensin System Inhibition in Advanced Chronic Kidney Disease

Sunil Bhandari , Samir Mehta , Arif Khwaja , John G F Cleland , Natalie Ives , Elizabeth Brettell , Marie Chadburn , Paul Cockwell , STOP ACEi Trial Investigators

PMID:36326117

Introduction

It may sound like a cliche, but renin-angiotensin system (RAS) inhibitors, including angiotensin-converting–enzyme inhibitors (ACEi) and angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARB), are a cornerstone of chronic kidney disease (CKD) management since the 1990s. Several trials have demonstrated that use of RAS inhibitors slows CKD progression and reduces proteinuria in patients with proteinuric CKD (Lewis et al, NEJM 1993; GISEN, Lancet 1997; Jafar et al, Ann Intern Med 2001; Brenner et al, NEJM 2001; Lewis et al, NEJM 2001). So why should we ever stop them?

The concerns around RAS inhibitor use in advanced CKD are well summarized in the infographic below. Indeed, it is not unusual that RAS inhibitors are stopped (or withheld) when there is trouble with hyperkalemia or out of desperation to buy some time when the dreaded dialysis looms near. A theoretical benefit of discontinuing these agents in this population would be buying time to allow for vascular access maturation or transplant work-up. But RAS inhibitors are drugs with benefits - lowering blood pressure and proteinuria, as well as decreasing adverse CV outcomes. Hence, conversely, bravely continuing RAS inhibitors in advanced CKD may help with improved cardiovascular outcomes, decreased incidence of stroke, lower mortality rates, and potentially, slower progression to end stage kidney disease (ESKD). Continuing these first-line antihypertensive agents may also enable better blood pressure control, which may help limit the use of other agents that do not confer any clinical benefit, such as hydralazine and alpha blockers.

While RAS inhibitor-mediated slowing of CKD progression has been demonstrated time and again in earlier stages of CKD, whether this benefit of RAS inhibitors persists in the setting of advanced CKD is not well known. The existing data came from a small single-center, 52-patient cohort in the UK. In this study RAS inhibitors (ACEi or ARB) were discontinued by patients followed in the advanced kidney care clinic. After discontinuation, they had systematic modification of their anti-hypertensive regimen, with different protocols based on whether the patients had concomitant, symptomatic congestive heart failure (CHF) (n=7). The authors demonstrated a significant rise in eGFR of approximately 10 ml/min/1.73m2 12 months after discontinuation of RAS inhibitors, which reportedly delayed the onset of renal replacement therapy (RRT) in this cohort. Based on these data, they encouraged caution in using these agents in the setting of advanced CKD approaching RRT (Ahmed et al, NDT 2010).

Though this approach seems plausible, the proof lies in the metaphorical RCT pudding. To this end, the STOP ACEi investigators sought to assess whether discontinuing RAS inhibitors in patients with stage 4-5 CKD would slow down CKD progression.

The Study

Methods

STOP ACEi was a multi-center, randomized, open-label trial that examined the impact of continuation of RAS inhibitors on the eGFR in advanced CKD. Patients were enrolled at 39 centers in the United Kingdom. RAS inhibitors were defined as ACEi or ARB.

Study Population

Inclusion criteria

1. Adults >18 years old

2. CKD Stage 4-5 (eGFR < 30 ml/min/1.73m2)

3. Decrease in eGFR >2 ml/min/1.73m2 per year in the previous 2 years

4. Receiving treatment with an ACEi, ARB or both for > 6 months

Exclusion criteria

1. Receiving dialysis

2. Having had a kidney transplant

3. Uncontrolled hypertension (BP > 160/90 mmHg)

4. Immune mediated kidney disease requiring specific therapy

5. MI or stroke within the previous 3 months

It is important to note that patients with uncontrolled hypertension and recent MI or stroke, who were more likely to benefit from ongoing RAS inhibition, were excluded from the present study.

Intervention

Study participants were randomized in a 1:1 fashion to continue RAS inhibitors or to discontinue them. In the group that continued RAS inhibitors, the dose and specific agent were at the discretion of the care provider. Both groups were allowed to have any guideline-recommended antihypertensive added to their regimens to meet the study blood pressure target of <140/85 mmHg, including MRAs (which also inhibit RAS via mineralocorticoid receptor antagonism). Patients in the discontinuation group were not to resume ACEi or ARB unless all other options were ineffective or associated with intolerable side effects. Participants were followed every 3 months after randomization for a total period of 3 years.

Trial endpoints

Primary endpoint

The eGFR at 3-years follow-up calculated using the 4-variable MDRD175 equation was the primary end-point. This was censored when someone started dialysis or received a kidney transplant.

They also repeated the primary analysis using the CKD-EPI 2009 equation and the MDRD186 equation. The MDRD186 equation was developed in 1999 in a predominantly Caucasian non-diabetic population. As it tends to underestimate measured GFR at higher values of eGFR, values greater than >60 ml/min/1.73m2 cannot be reported numerically. The equation was adjusted in 2005 to account for standardized serum creatinine assays, giving us the MDRD175 equation. The CKD-EPI 2009 equation was developed in a more diverse cohort, with respect to age, kidney disease, kidney function and ethnicity. The CKD-EPI equation is as accurate as the MDRD equation at lower GFRs, but outperforms the MDRD equation in people with higher levels of GFR.

Secondary endpoints

1. Time to development of ESKD (defined by the local investigator, with criteria including palliative care and RRT)

2. Composite including decrease in eGFR > 50%, development of ESKD and initiation of KRT

3. Any cause hospitalization

4. Blood pressure measures

5. Quality of life (Kidney Disease Quality of Life 36-Item Short Form Survey, version 1.3)

6. Exercise capacity (6-minute walk test)

7. CVD events

8. Death

9. Hemoglobin

10. Urinary Protein-to-creatinine Ratio (uPCR)

Statistical Analysis

The study used intention-to-treat analysis. The difference in eGFR between the two groups at 3-years was estimated using a repeated-measures, mixed-effects, linear regression model. eGFR data after starting dialysis or getting transplanted were censored.

Sub-groups examined included:

T1DM, T2DM, no diabetes

MAP < 100 mmHg vs > 100 mmHg

Age <65 years vs >65 years

uPCR <885 vs >885 mg/g

eGFR < 15 vs >15 ml/min/1.73m2

Continuously distributed secondary outcomes (i.e. blood pressure) were also analyzed using a repeated-measures, mixed-effects, linear regression model. Categorical secondary outcomes (i.e. CVD events) were analyzed using a Poisson regression model. Time-to-event outcomes were examined using a Cox proportional-hazards model to calculate hazard ratios and 95% CIs.

Funding

There was no industry funding for this study. The project was funded by the National Institute for Health Research and the Medical Research Council.

Results

Study Population

There were 17,290 patients screened between July 11, 2014, and June 19, 2018. Of these, 1,210 patients were invited to participate, and 411 patients (from 37 centers) were randomized. Patients were followed until June 19, 2021. Participant flow through the study is summarized in Figure 1 from the paper.

Figure 1 from Bhandari et al, NEJM 2022

The median age of the study population was 63 years, with a median eGFR at baseline of 18 ml/min/1.73m2 (29% had a baseline eGFR <15). There were 281 (68%) male participants, and only 60 (15%) patients were non-White. Median uPCR was 1018 mg/g. A minority (17%) of participants had a history of MACE at baseline. Diabetes (T1DM or T2DM) was present in 153 (37%) patients and 87 of them were thought to have (21%) diabetic nephropathy. Only 4% of patients were thought to have heart failure at baseline, and their baseline ejection fraction was not reported. Most participants (58%) were on three or more anti-hypertensive agents at the time of enrollment. It would have been interesting to see the baseline KFRE-risk scores of both cohorts reported to help contextualize risk profiles for CKD progression.

Table 1 from Bhandari et al, NEJM 2022

Primary outcome

At 3-years, the least-squares mean eGFR in the continuation group was 12.6 ± 0.7 and was 13.3 ± 0.6 in the discontinuation group (p = 0.42) (Figure 2A). The analyses using the MDRD186 and CKD-EPI 2009 equations performed similarly to the MDRD175 equation.

Figure 2A from Bhandari et al, NEJM 2022

There was no significant difference in the primary outcome of eGFR at 3-years in the subgroup analyses (summarized in Figure 2B below).

Figure 2B from Bhandari et al, NEJM 2022

Secondary outcomes

ESKD or RRT at 3-years occurred in 128 (62%) patients in the discontinuation group and 115 (56%) patients in the continuation group (HR 1.28, 95% CI 0.99-1.65).

The composite outcome of ESKD, KRT or decrease in eGFR > 50% happened in 140 (68%) participants in the discontinuation group and 127 (63%) participants in the continuation group (adjusted RR 1.07, 95% CI 0.94-1.22). There were similar numbers of all-cause hospitalizations and death between the two groups. CVD events were also reported to be similar, although we note there were relatively fewer events in the continuation arm (n=88) than the discontinuation arm (n=108). There were also no between group differences with respect to distance covered during the 6-minute walk test and the quality-of-life measures.

Although blood pressure control was poorer in the discontinuation group during the first 15 months of the trial, blood pressure values were similar between the two groups thereafter. The authors report that this was because of the addition of different antihypertensives, but did not report specifically which classes of medications were added.

Figure S19A and B from Bhandari et al, NEJM 2022

Similarly, proteinuria was higher in the discontinuation group in the first year of the trial but was not significantly different thereafter.

Of the 490 serious adverse events, 21 were reported to have been potentially related to the trial-group assignment, with no significant between group differences reported. These 21 events were not explicitly identified in the study. Of note, there were a total of 6 hyperkalemia events reported, of which 2 occurred in the discontinuation arm and 4 occurred in the continuation arm. It is unknown whether patients enrolled in this study were concurrently on potassium binding therapies. There was no difference in heart failure, cardiovascular, and vascular events between the two arms.

Table 2 from Bhandari et al, NEJM 2022

Discussion

The STOP-ACEi trial did not find any benefit by stopping ACEi (or ARBs) in advanced CKD. Indeed, the discontinuation arm had a 6% numerically higher risk of needing KRT, and numerically higher risk of CV events as well. Thus, the findings of the STOP ACEi trial clearly overturn the results of the previously 2010 study by Ahmed et al. in the 52-patient UK cohort. This is why, as plausible they might be, we need to confirm observations with experiments, wherever possible.

After STOP ACEi was designed, a nation-wide observational study using a target trial approach from a Swedish cohort was published (see the NephJC on a different study using similar methodology for more on this approach). Contrary to the findings in the present study, discontinuation of RAS inhibitors was associated with decreased risk of starting KRT. However, there was also a notably higher risk of mortality and MACE, leading the authors to suggest against routine discontinuation in advanced CKD (Fu et al, JASN 2020). Another observational study conducted in the United States similarly reported that discontinuation of ACEi or ARB was associated with a higher risk of both mortality and MACE, but found no statistically significant difference in the risk of ESKD (Qiao et al, JAMA Intern Med 2020). These studies are consistent with the 2012 KDIGO CKD guidelines which recommend against routine discontinuation in patients with eGFR <30.

Going back to our “to continue or not to continue” infographic, it does seem that discontinuation of RAS blockade in patients with advanced CKD due to concerns around tolerability, hyperkalemia or polypharmacy with concurrent diuretics or potassium binders, or to buy time for access creation or transplant work-up, would not be terribly unsafe as long as other agents are introduced to maintain blood pressure control. However, it is important to note that the STOP ACEi trial was not adequately powered to examine the effect on mortality or cardiovascular outcomes. The cardioprotective benefits of RAS inhibitors in advanced CKD have been previously demonstrated in the aforementioned large observational studies (Qiao et al, JAMA Intern Med 2020; Fu et al, JASN 2020), which does further support against routine discontinuation of RAS inhibitors in stage 4-5 CKD.

Strengths

This was a well-designed, randomized controlled trial, with even representation of patients with diverse etiologies of CKD (including ADPKD).

Limitations

The study cohort was primarily White participants, limiting the generalizability of these findings to other ethnicities. Additionally, the authors did not include dosing information for the RAS inhibitors or the other guideline recommended anti-hypertensive agents used in the study. These details, particularly what proportion of the participants in the continuation arm were using maximally tolerated doses compared to lower doses, would be important to contextualize the findings to readers’ clinical practices and to allow for comparisons with the existing literature. The open-label nature of this study may have contributed to bias, particularly with respect to subjective endpoints (e.g. quality-of-life). Additionally, in open-label trials such as this one, care providers are more aggressive with adding back anti-hypertensive agents to meet blood pressure targets, compared to the real-world setting wherein patients who have stopped RAS blockade may simply have ended up with worse blood pressure control.

What questions remain?

There was a relatively low proportion of patients included who had a history of congestive heart failure despite the considerable burden of CHF in this patient population. This may be related to reluctance to include these patients who are on ACEi or ARB as part of goal-directed medical therapy for CHF knowing they may be randomized to stop them. It would be interesting to determine whether continuation or discontinuation of angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitors among patients with both advanced CKD and CHF would perform similarly to ACEi or ARB in the present study.

Conclusions

The results of this trial confirm that discontinuation of ACEi or ARB in patients with advanced CKD does not provide meaningful improvement of kidney function. The decision to continue or discontinue RAS inhibitors should be made in the context of the individual patient’s level of proteinuria, blood pressure control, tolerability and cardiovascular risk profile. A knee jerk response of stopping RAS inhibitors in advanced CKD at an arbitrary GFR threshold is incorrect. Keep Calm and Carry on Inhibiting the RAS.