The next NephJC is August 9th and August 10th.

We will be discussing:

A sustained quality improvement program reduces nephrotoxic medication-associated acute kidney injury.

Goldstein SL, Mottes T, Simpson K, Barclay C, Muething S, Haslam DB, Kirkendall ES

PMID: 27217196

But don't be confused by that stodgy name, this article is really called NINJA: Nephrotoxic Injury Negated by Just-in-time Action

It was published in Kidney International and will be able for free from August 5-12 at this link.

NephJC work group member, Michelle Rheault, wrote the summary.

Introduction

Exposure to nephrotoxic medications in hospitalized children is very common. In one recent study, 86% of non-critically ill, hospitalized children were exposed to at least one nephrotoxic drug and almost a third developed acute kidney injury (AKI). AKI in turn increases the risk of mortality, length of stay, hospital costs, and long term risk of developing chronic kidney disease. All things we desperately want to avoid in children. Dr. Stuart Goldstein (@WePaki1964) and colleagues at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center developed a novel way to screen patients for nephrotoxic exposure and avoid AKI: the NINJA project (Nephrotoxic Injury Negated by Just-in-time Action). In case anyone was keeping score, I think the pediatricians just won Best Study Acronym Ever (Take that AKIKI).

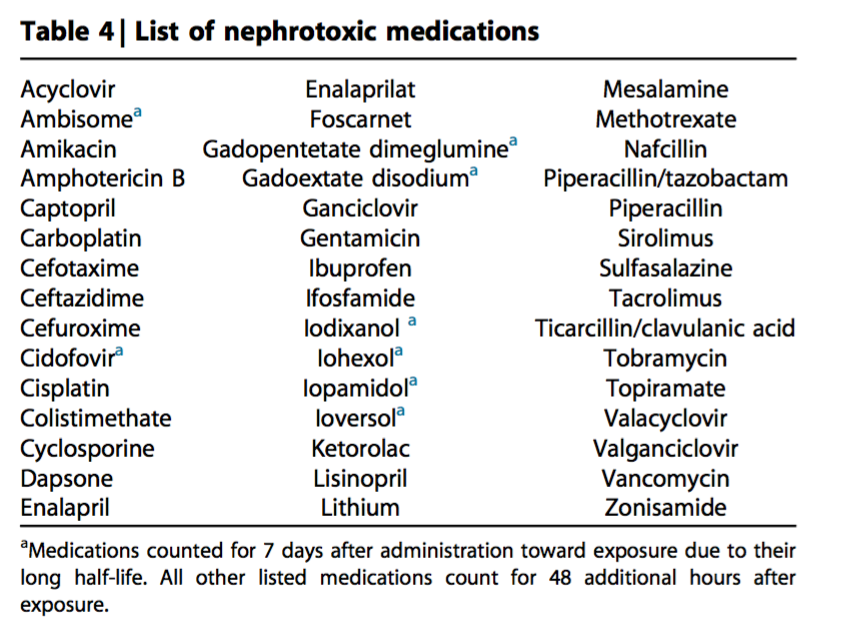

NINJA is a quality improvement (QI) project implemented in 2011 at a single quaternary pediatric hospital. The concept was simple: Identify hospitalized children who are at risk for AKI based on their nephrotoxic medication exposure and encourage providers to order a daily creatinine. If a child received 3 or more days of an aminoglycoside or 3 nephrotoxic medications (Table 4) simultaneously, they were included in a daily email report to the pharmacist who rounded with each inpatient team.

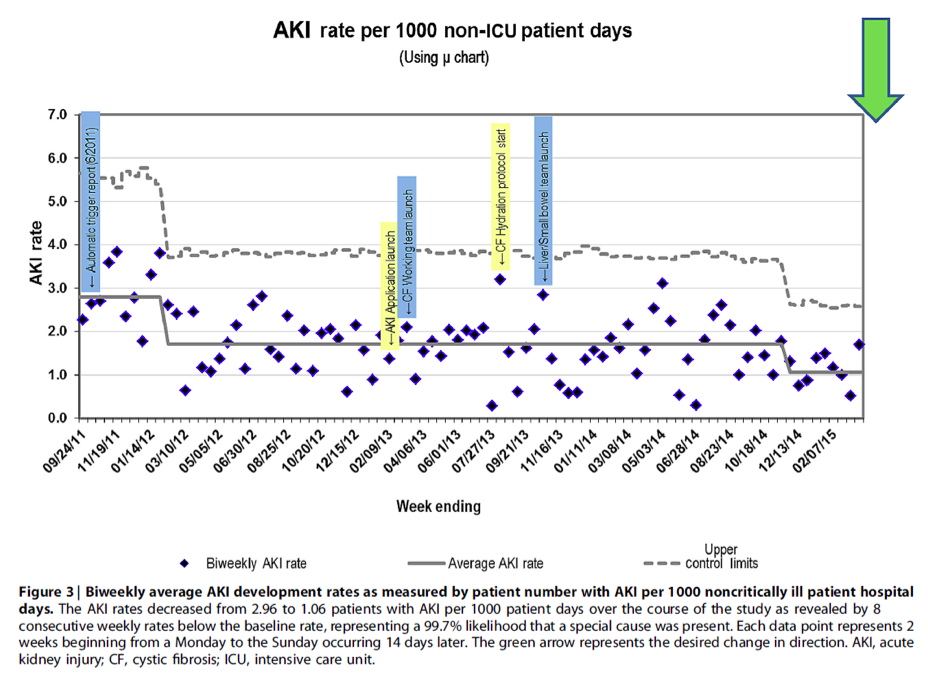

The pharmacist would then make sure creatinines were checked and drug monitoring was implemented. Pharmacists could also make suggestions about changing the drug but this was not required. For the first 3 months of the project, the nephrotoxic medication exposure was determined manually by the pharmacists. But aft that the EPIC electronic health record was configured to give an automated readout. The NINJA team got enormous buy-in from their inpatient teams with >99% of requested creatinine values obtained. Of course, attending physicians who declined to order a creatinine got a friendly call from Ninja Goldstein to discuss their rationale. The initial results showed a 42% reduction in AKI intensity over 1 year (defined as # of days patients have AKI divided by the # of susceptible patient days). This week's #NephJC is on the three year follow up to determine if improvements in AKI rates were sustained.

Methods

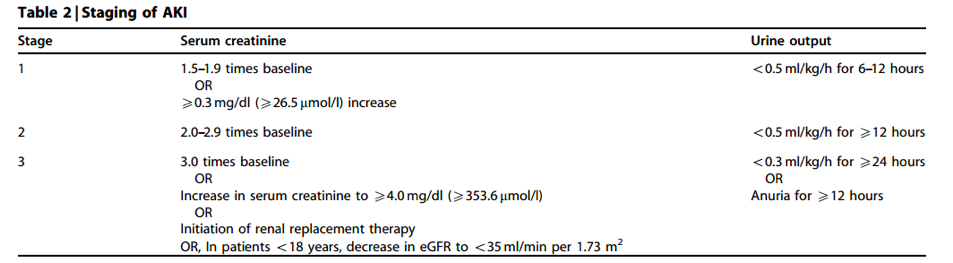

All non-critically ill children admitted to Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Sept 2011 to March 2015 were included. NINJA emailed pharmacists with all the children exposed to nephrotoxins. This list was generated automatically by EPIC. The list was reviewed on rounds with the inpatient team. Pharmacists recommended a creatinine for exposed children. AKI was defined per KDIGO:

If a baseline creatinine was unavailable (as is often the case in a child on an inpatient ward), a presumed estimated creatinine clearance of 120 ml/min/1.73m2 was used.

Four main outcome measures were included:

Results

1,749 patients with 2,358 admissions were included. 575 individual AKI episodes were observed (47% stage 1, 33% stage 2, and 20% stage 3).

Nephrotoxic medication exposure rate decreased by 38% (from 11.63 to 7.24 patients/1000 patient days)

AKI rates decreased by 64% (from 2.96 to 1.06 patients with AKI/1000 patient days) during the study period.

There was no difference in the medication classes used or the admitting service distribution during the study period to explain the improvements. (No, the BMT unit didn’t close down, nor did the hospital have a shortage of vancomycin).

Summary and archive of the chat on NINJA