Preamble

This page discusses the common questions transplant professionals as well as transplant patients may have with respect to Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19). We have few facts and little evidence, and those are laid out below. Hence the other points discussed below are mostly based on biological plausibility, common sense, and expert opinions. Individual patient decisions depend on local resources, logistics and other factors, and hence practice will vary appropriately from location to location. For more on the topic of COVID-19 in general, visit the main NephJC page.

A few words about the state of SARS-CoV2 science

Before we start reviewing the literature it is important to recognize the current landscape of peer review (or lack thereof). Especially in the fast moving world of COVID19 research. Brian Byrd provides a nice overview here. He describes the differences between preprints, letters to the editor, rapid response, and other publication types in detail.

Last Update: July 22, 13:56 Eastern

What was updated: List of contributors

Contributors

Bea Concepcion, MD, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN Mona Doshi, MD, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor MI Samira Farouk, MD, MS, FASN, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York NY Swapnil Hiremath, MD, MPH, University of Ottawa, Canada

Syed Husain, MD, Columbia University, New York NY Michelle Lim, Dundee, Scotland

Ian Logan, Newcastle Hospitals, Newcastle, UK

Olivia Kates, Infectious Disease Fellow, University of Seattle, Seattle WA Edoardo Melilli, Catalonia, Spain

Paul Phelan, Royal Infirmary, Edinburgh

Cathy Quinlan, Royal Children’s Hospital, Melbourne, Australia

Roger Rodby, MD, Rush University, Chicago IL

Silvi Shah, MD, MS, FASN, University of Cincinnati OH

Laura Slattery BSc BMBS, Cork University Hospital, Ireland

Beje Thomas, MD, MedStar Georgetown Transplant Institute, Washington DC Tiffany Truong, University of Southern California, Los Angeles CA

Curated and Edited by

Swapnil Hiremath, MD, MPH, University of Ottawa, Canada

Joel M. Topf, MD, FACP Oakland University William Beaumont School of Medicine, Rochester, MI

Official Resources

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): How to Prepare and Protect

The American Society of Transplantation (AST) answers FAQ’s for transplant professionals and transplant recipients and candidates, they have compiled a list of online resources for the transplant community, and recently had a Organ Donation and Transplant Town Hall relating to COVID-19.

Advice from The Transplantation Society (TTS)

European Society of Organ Transplantation Resources

The ERA-EDTA resource page, with links to the ERACODA registry reports

British Society of Transplant COVID-19 resource page

The American Society of Transplantation second Town Hall on COVID-19 took place on April 13. A distinguished panel of speakers provide an update from trends in transplantation, registry data, the New York experience, discharge, and resource management to AKI, cardiac/pulmonary/critical care, and therapeutics. This a wonderful comprehensive review of where we are today with the COVID-19 pandemic and transplantation. See the full video below:

Patient FAQs

What is the risk of COVID-19 in kidney transplant recipients?

There is no specific published data on the risk of COVID-19 in transplant recipients. Kidney transplant patients are presumed to be at higher risk, given the suppressed immune state. We will update this as firm data becomes available.

What can kidney transplant recipients do to decrease their risk of COVID-19?

Similar to what the general population is doing to reduce risk, including social distancing and avoiding non-essential travel. Patients should discuss with their transplant team if they can have in person or telemedicine (by computer or phone) clinical visits to reduce exposure and the plans for lab work and receiving medications.

What should we do about outpatient follow up of transplant recipients if we have concerns about COVID-19 prevalence in the community?

Local arrangements will differ around the world but most outpatient visits should transition to telehealth visits using a combination of phone and video conferencing and bloods only visits. Here is a presentation by Daniel Choi et al, why this is beneficial i.e. flatten the curve. For some patients who are stable, the length of time between reviews may be extended. Patients can be followed by general practitioners not only nephrologists. In addition if you are in the evaluation process for a transplant or are on the waitlist and have a check up visit scheduled, check with the transplant center on how to proceed.

If you will be doing these virtual visits make sure you have access to the internet and check with your transplant team to make sure you have an appropriate smartphone.

In the United Kingdom for example, patients taking immunosuppression have been identified as ‘extremely vulnerable’ by Public Health England and the current advice is shielding at home for 12 weeks, and avoiding face-to-face contact when possible.

Should we change anti-rejection medications preemptively if there is ongoing community spread?

The transplant societies are unanimous in urging people not to changing immunosuppression preemptively even with ongoing community spread.

Do not stop or change your medications without discussing with your transplant team.

Reduction of immunosuppression may precipitate rejection; which usually means hospitalization and even greater exposure to immunosuppression and risk.

We advocate tracking your supplies, confirming with your pharmacy that the medications will be delivered, and discussing with your transplant team about a backup supply.

What should I do if I am exposed to someone with COVID-19?

In those transplant recipients with a significant exposure to COVID-19 but who are not yet proven to have COVID-19, any decision to alter immunosuppression should be made on a case-by-case basis and might be influenced by factors including time since transplant, the age of the transplant recipient, and the presence or absence of other health conditions.

Is there a role for prophylaxis for COVID-19, specifically with drugs such as hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine?

There is currently no evidence to support the use of prophylaxis for COVID-19 in transplant patients. This is being discouraged as misuse can lead to toxicities that can be harmful and possibly lethal. For example, hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine can cause GI symptoms, bone marrow suppression, retinopathy and vision issues, and prolongation of the QT interval putting people at risk of fatal heart arrhythmias. Read more about this on the main NephJC page (section on ‘Note on Hydroxychloroquine and Chloroquine).

What should transplant patients do if they develop fever, flu-like or respiratory symptoms?

Patients who develop symptoms should call their transplant center so they can be directed to the appropriate assessment site and guidance can be given if they need COVID-19 testing. If a patient has a medical emergency and requires assessment in an Emergency Department, let the transplant team know in advance so they can coordinate and prepare the department for your arrival.

What changes should be made in immunosuppression for transplant recipients who develop COVID-19?

In confirmed positive cases of COVID-19, immunosuppression will be reviewed and is likely to be reduced by your transplant team. This should be decided on a case by case basis, but might involve withholding mycophenolate or azathioprine in those patients who also take tacrolimus or cyclosporine.

Mental wellbeing during the crisis

The CDC’s statement and a compilation of resources on managing anxiety and stress during the COVID-19 pandemic

FAQs for Transplant Professionals

A compilation of the responses and experiences of transplant centers and professionals throughout the world is compiled here by the Transplantation Journal. This report highlights the immediate responses undertaken in different countries experiencing different phases of the pandemic.

What can a transplant center do to facilitate screening and testing of their patients?

Create appropriate workflows taking into consideration current needs and available resources

Establish a single hotline for transplant patients to call ignorer to provide guidance for symptomatic patients including appropriate triaging

Set up an assessment site dedicated to transplant patients where patients can be screened and tested for COVID-19 while being separated from non-transplant patients

Who can be seen through telemedicine or have a phone consultation instead of an in-person visit?

Telemedicine visits or phone consultations are being encouraged to reduce the risk of exposure for both patients and providers. In general, patients who are doing well without acute or ongoing issues are good candidates for a telemedicine visit. If resources prevent Telehealth visit, a phone consultation should be considered. This will however need to be determined on an individual basis and this may vary depending on transplant center protocol. Similarly, the need for laboratory tests and when these need to be obtained will need to be determined on an individual basis.

Should we continue doing living donor kidney transplants in these troubled times?

Here are online resources:

UNOS member information patient on COVID-19

American Society of Transplant Surgeons

The decision to continue with transplantation is center-specific at this time though there are, or will be formal regional or government mandates soon.

Since continuing with transplant activity is a risk management decision with competing risks that are changing each day, let's examine the pros and cons.

The risk of transplantation in the current environment is increased due to the relatively higher level of immunosuppression in the immediate and early post-transplant period, and the number of clinic visits in the early post-transplant period.

Both donor and recipient will require hospital beds, and operating room spots. The surgeries entail nurses, anesthesiologists and other health care personnel, who may be needed for the COVID-19 response.

On the other hand, transplantation takes a person off dialysis and is associated with better outcomes. So ideally, any such decisions should be made in consultation with the patient, though the fast-moving pace of this pandemic may make this impractical.

Many programs have already suspended their living donor transplant programs although some have taken a case by case approach and only excluded certain procedures (pre-emptive, HLA/ABO incompatible transplantation).

Paediatric transplantation centres may not experience the same resource limitation as adult centres during this pandemic so the transplantation needs of children should be considered separately.

These issues and trade-offs are discussed in this viewpoint (Kumar et al, Am J Transpl, 2020).

Should we continue doing deceased donor transplants?

Deceased donor transplant activity is being severely impacted by the current situation, again with several programs making the decision to cease all activity. Other jurisdictions are limiting certain procedures (pancreas transplantation, incompatible transplantation) and considering limiting procedures which may delay patient recovery and require a prolonged hospital stay (i.e.donation after circulatory death organs, older donors).

Similar to living donor transplantation, concerns about proceeding with deceased donor transplantation include the need for immunosuppression, the need for hospitalization and possibly rehospitalization, and the need for postoperative clinic visits. Other concerns include the need for deceased donor and possibly recipient testing for SARS-CoV2 prior to proceeding with a transplant, which can be limited by the test’s local turnaround time. The decision to test donors and recipients is currently center-specific but is encouraged. The lack of critical care resources will limit deceased donation, and general healthcare capacity will put constraints on post-transplant management in both inpatient and outpatient settings.

Should we have any other concerns with deceased organs during this crisis?

In other words, should we be concerned about transplanting kidneys from deceased donors? The kidney expresses ACE2, which is hijacked by SARS-Cov2 to enter the cells. (See more about this aspect here on the NephJC COVIDACE2 page). An autopsy preprint study (Diao et al, MedRXiv 2020) also could isolate the SARS-Cov2 nucleocapsid antigen in the kidneys. Can’t we just test the potential deceased donor and only accept organs from someone who are negative for SARS-CoV2? This is probably a bad idea due to the potential for false negative results. Deceased donor transplantation in general during a COVID-19 outbreak is probably a bad idea.

Even as the epidemic wanes, concerns about transplantation will persist. The viewpoint paper (Kumar et al, Am J Transpl 2020) also discusses a donor screening tool, and the British Transplantation Society discusses the issues around consent in this setting (BTS guidance, 2020, PDF).

How does COVID-19 present in kidney transplant recipients?

While many clinicians have been concerned that chronic use of immunosuppression would make kidney transplant recipients more vulnerable to severe COVID-19 presentations, others have postulated that these medications may lead to milder initial presentations. Early data was limited to international case reports. A case report from Spain (Guillen et al Am J Transpl, 2020) described the identification of COVID-19 in a patient 4 years after his third kidney transplant who initially presented with only persistent fever before eventually developing cough 5 days later. In contrast, a report from Wuhan, China (Zhu et al, Am J Transpl 2020) described typical initial symptoms, including cough, fatigue, dyspnea, and chest tightness, in a patient with COVID-19 who had previously undergone living related kidney transplantation 12 years earlier.

Larger case series have now begun to be reported. In a case series of 15 inpatient kidney transplant recipients at Columbia University in New York City with COVID-19 (Columbia U Kidney Tx Program, JASN, 2020), presentation was similar to the general population: 87% reported fever, 60% reported cough, and all but 1 patient had either fever or cough.3 While these patients most commonly had multifocal opacities on chest x-ray (47%), 33% had normal radiographs. Additionally, while median white blood cell count was only 4.8 x1000/μl, most patients had elevated inflammatory markers including ESR (median 40 mm/hr), CRP (104 mg/L), and IL-6 (24 pg/mL). These findings are similar to an Italian cohort of 20 kidney transplant recipients admitted for COVID-19 at the University of Brescia, where all patients reported fever, and 50% reported cough (Alberici et al, Kidney Int 2020). The Italian cohort also noted half of their patients had bilateral infiltrates on presentation, with 15% having no infiltrates. Median WBC was 5.4 x1000/μl, with median CRP 49mg/L.

Thus, in summary, data to date suggests kidney transplant recipients with COVID-19 typically present with similar symptoms and signs as the general population, including fever, cough, and bilateral infiltrates on chest x-ray.

How should we treat COVID-19 in a transplant recipient?

An overview of infections in the solid organ transplant recipients is provided in this review by Fishman (Am J Transpl 2017). For COVID-19, we have no clinical trial data but only anecdotal data to guide us at this time. There is no clear answer regarding “if” or “how” immunosuppression should be reduced. The following discussion is mostly based on biology and pharmacology and is written to help think through clinical-decision-making in the face of uncertainty. In the transplant field a viral infection may precipitating acute rejection (which may cause graft failure or create the need for further immunosuppression). One must be aware that COVID-19 treatment regimens have included high dose steroids, IVIG, and other immunomodulating agents. Therefore though typical maintenance transplant immunosuppression might change, the patient is still being exposed to medications that affect the immune system. Remember, in reading the present data one must do their own due diligence and thoughtfully look at the information presented because the usually rigorous peer-reviewed publication process is not be as strict as usual.

With those caveats, we will briefly discuss the reported interventions.

Reduction in existing immunosuppression

You have an infection, why not reduce the immunosuppression? From the usual cyclosporine/tacrolimus (CNI) + mycophenolate/azathioprine + steroid protocol, often the middle one is the first to go. There is no data to guide us on what is the right thing to do in this particular setting of COVID-19.

What we do know is that the risk of rejection is higher when we withdraw even one of these agents. The elective withdrawal of a CNI increases the risk of acute rejection with a summary odds ratio of 2.23 in the systematic review by Moore et al (Transplantation, 2009). For withdrawal of mycophenolate on the background of a tacrolimus-based protocol, the risk of acute rejection was not significantly higher in this review by Su et al ( Annals of Pharmacotherapy, 2011).

Additionally, some intriguing basic science data suggests that CNI agents might inhibit growth of coronaviruses. Carbajo-Lozoya et al, (Virus Research 2012) showed that both cyclosporine and tacrolimus inhibited the replication of coronaviruses SARS-CoV, HCoV-NL63 and HCoV-229E. Similar results have been reported with the HCoV-229E, with elucidation that the CNIs act via inhibition of the cyclophilin A pathway. See Ma-Lauer et al (Antiviral Research, 2020). We don’t know if this effect will occur in vivo, in humans, and at a level beneficial in COVID-19. A longer description of this aspect is described in this recent review (Willicombe et al, JASN 2020). This discussion provides some (weak speculation, at best) support for the continuation of CNIs over the antimetabolite drugs.

What should we do with steroids?

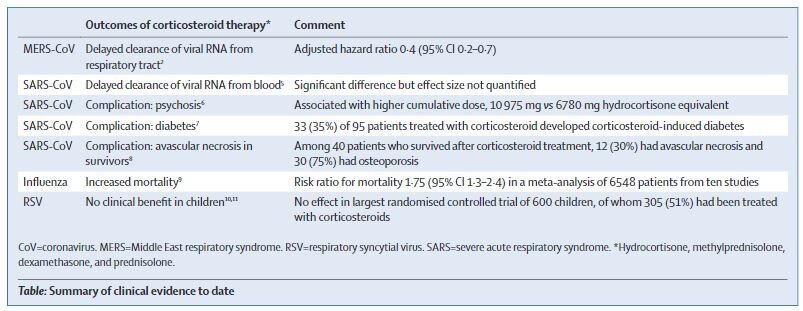

Often when we withdraw one of the three immunosuppressive agents, we increase the dose of steroids, to reduce the risk of acute rejection. What role do steroids play with COVID-19? Unfortunately, higher dose steroids are associated with longer duration of viral shedding (non-SARS human coronaviruses, Ogimi et al J Inf Dis 2017) and higher viral loads (porcine model of classic SARS, Zhang et al, J Virol 2008, human case series in classic SARS, Lee et al, J Virol 2004). A summary of the clinical evidence is provided by this table from a recent correspondence in the Lancet (Russell et al, Lancet 2020).

Table from Russell et al, Lancet 2020

On the other hand, these data are from non-transplant settings, and the need for a higher dose of steroids is also for prevention of acute rejection. Additionally, sometimes steroids are used in the critically ill patients for other reasons, and that is at the discretion of the intensivists along with the nephrology/transplant team.

See below for a simplified algorithm for the British Transplantation Society

Appendix from BTS guidance

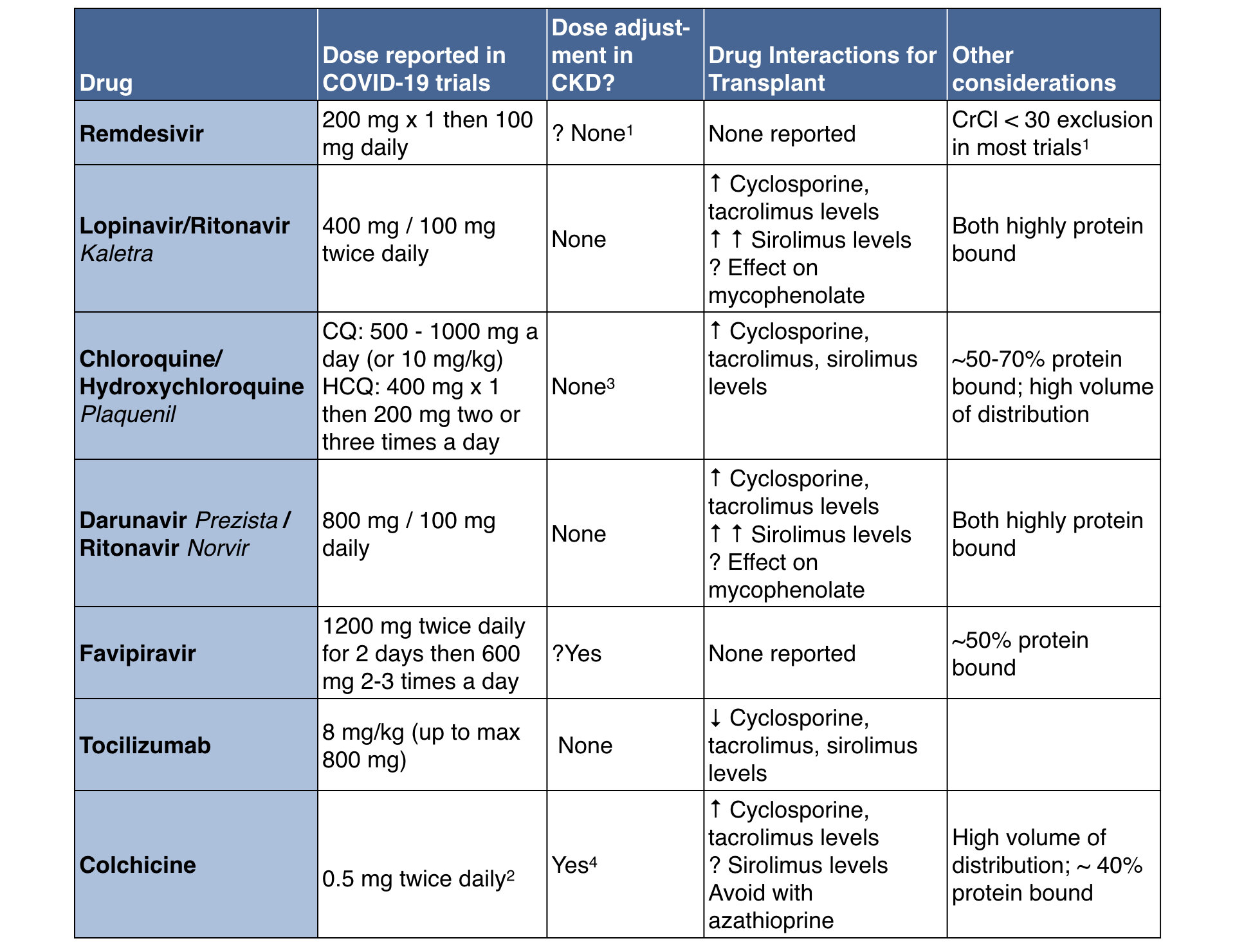

Experimental therapies

Careful consideration of drug dosing and interactions, particularly interactions with immunosuppression will need to be included in treatment plans, for example interactions between clarithromycin, and similar antibiotics, with tacrolimus. Here is a PDF to potential drug interactions from University of Liverpool’s Prescribing Resources to be aware of when considering COVID-19 treatments.

See below for a quick summary. As always, a consultation with a clinical pharmacist will be useful in this setting.

Names in italics refer to brand names.

1: This is a common reported exclusion. We are not sure of the data behind this. See discussion of this in this Twitter thread.

2: Dose in gout is usually 0.6 mg, this dose is reported for the COLCORONA trial 3: These drugs do have some clearance by kidneys, so accumulation with occur with chronic dosing, not relevant in the COVID-19 setting

4: CrCl < 30 an exclusion in the COLCORONA trial

Actual Clinical Evidence

This is currently sparse. Beyond anecdotes, we will add case reports and case series as they accumulate here. Fortunately, some journals such as the Am J Transpl have committed to publishing case reports expeditiously to help guide us in real time.

A case report of 2 heart transplant recipients who developed COVID-19. The team held their immunosuppressants, continued steroids and added IVIG. Both patients recovered (Cai et al, J Heart and Lung Transpl, 2020).

Another case report of a kidney transplant recipient with COVID-19 who had a good outcome after stopping all immunosuppressives initially and then subsequently received IV methylprednisolone, IVIG and other supportive management (Zhu et al, Am J Transpl 2020)

A case report by Guillen et al (Am J Transpl, 2020) describes a kidney transplant patient who presented with gastrointestinal symptoms initially, then with a pneumonia and hyponatremia before the diagnosis was made. They were treated with lopinavir/ritonavir while both the CNI and everolimus were withdrawn. They also received hydroxychloroquine followed by interferons. The patient remains in the ICU, but without further progression.

A case report of 2 patients from Italy (Gandolfini et al, Am J Transpl 2020). Both treated with withdrawal of CNI and MMF and addition of antivirals (lopinavir+ritonavir or darunavir+cobicistat) and hydroxychloroquine. One person worsened suddenly and passed away. The other one received colchicine (the plan was for tocilizumab which was not available) and improved, though remains on non-invasive ventilation.

In addition, the University of Washington Solid Organ Study Group is collecting data as well, and issues weekly reports. As of 3rd April, there are 75 patients accrued, and you can click on the link below for details. It seems that stopping azathioprine and mycophenolate is a common strategy; 66% required hospitalization so far, 28% in the intensive care unit. There doesn’t seem any magic bullet apparent so far (including hydroxychloroquine).

Now we are getting larger case series being published, as described below

In the first published cohort of five COVID-19 positive renal transplant recipients from Wuhan (Zhang et al, European Urology, 2020), four of which were male, all presented with a fever and cough and three reported myalgia or fatigue. All patients developed lymphopenia, and high CRP. Interestingly, four developed new onset proteinuria. Four patients were taking triple immunosuppression consisting of Prednisolone, Calcineurin inhibitors and MMF. The MMF was stopped in four patients, and Calcineurin inhibitor and steroid doses were reduced. All patients received antiviral therapy and although all patients had lung infiltrates on radiological investigation, no patient developed severe COVID-19 infection or required ventilation or intensive care.

In another cohort of seven COVID-19 positive renal transplant patients from London, all patients again presented with fever and all presented with respiratory symptoms of some form (Banerjee et al Kidney Int 2020). Lymphopenia and raised CRP was again common. Two of the reported cases occurred within 3 months of the global pandemic being declared, with a total of 32 kidney transplants being performed over the same time frame, all receiving relatively mild Basiliximab induction at the time of transplantation. The majority were again taking triple immunosuppression at the time of presentation. Five of the 7 cases required hospitalization, with four of these requiring escalation to intensive care. Of these four, 3 patients were notably diabetic. However, two of the original 7 cases, both of which were taking dual rather than triple immunosuppression and maintained normal lymphocyte counts were successfully managed at home, neither reportedly diabetic.

With respect to COVID-19 pneumonia specifically, in the largest published case series of 20 renal transplant patients from Italy, all again presented with a fever, and half had a cough (Alberici et al, Kidney Int 2020). Although only one reported breathing difficulties, half of patients already had bilateral lung infiltrates on initial radiographic imaging. These patients, predominantly male, were again mostly taking Calcineurin inhibitors and MMF at the time of presentation and were admitted a median of 5.5 days after first developing symptoms.

Over a 7 day period, the majority of patients in the Italian cohort above showed progressive lung changes on repeat imaging and despite all patients having their usual immunosuppression withdrawn, the administration of steroids, antivirals, Hydroxychloroquine, and in some cases Tocilizumab, 5 patients ultimately died due to complications of pneumonia. In the London cohort, after 3 weeks of follow-up, 1 patient died.

What is the Risk of AKI in transplanted patients?

Kidney transplant recipients can develop acute kidney injury (AKI) with COVID-19 just as other people. This can be acute rejection or COVID-19-related AKI. There is an excellent review of the topic of AKI at the NephJC AKI resource page. It would be important to recognize in transplanted patients, the timing of AKI with immunosuppression or drug changes not only for rejection but for drug specific toxicities such as AIN. Routine work up of AKI in transplant should be done to exclude other causes of AKI, remember what is common is still common. If no clear diagnosis kidney transplant biopsy should be considered with appropriate precautions and checking donor specific antibodies for a quick and hopefully decisive diagnosis. In the Italian series of 20 kidney transplant recipients who developed COVID-19 pneumonia, six patients developed AKI, with one requiring dialysis. In the London series of 7 kidney transplant recipients, 4 developed AKI.

List of updates

March 28: Page Launched

March 30: Added link to Kumar et al paper; discussion about resuming transplants; case report from Guillen et al

April 1: Added case report from Gandolfini et al

April 4: Contributors updated; Link to UW SOT study group data, April 3rd

April 12: Contributors updated; Link to UW SOT page Apr 10; data from 3 larger case series added to ‘actual clinical evidence’

April 15: Link to the AST townhall and video added

Apr 22: Link to case series from JASN from Columbia, review on CNIs added

July 22: List of contributors