#NephJC Chat

Tuesday May 22 9 pm Eastern

Wednesday May 23 8 pm BST, 12 noon Pacific

Ann Intern Med. 2018 Apr 17. doi: 10.7326/M17-2451. [Epub ahead of print]

The Drug Overdose Epidemic and Deceased-Donor Transplantation in the United States: A National Registry Study.

Durand CM, Bowring MG, Thomas AG, Kucirka LM, Massie AB, Cameron A, Desai NM, Sulkowski M, Segev DL.

PMID: 29710288

Also see related Editorial ‘Every Cloud has a Silver Lining’

Introduction

Newsflash: There is an opioid epidemic in the United States (US). In 2016, drug overdose deaths experienced the largest annual jump in the US. The opioid epidemic is now a public health crisis, with more than 115 people dying of an overdose every day. This surge in young, otherwise healthy people dying has led to an unfortunate increase in organ donors. These overdose-death donors (ODDs) may be Public Health Service (PHS) increased risk donors (IRDs) due to increased behaviors that increase the risk of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B (HBV), and hepatitis C (HCV).

With a seemingly large increase in the IRD donor pool, how should we consent potential recipients for a IRD? How would the same recipient do with a trauma-death donor (TDD) or medical-death donor (MDD) organ? How freely should we be transplanting these ODD organs? How often are they discarded? A 2017 study found that between 2010 and 2013, the PHS IRD label was associated with nonutilization of hundreds of organs, though the risk of disease transmission was low.

At the same time, the number of patients with kidney failure on the wait list is steadily increasing. 13 individuals die while waiting for a kidney transplant every day in the United States alone. At the same time, a new patient is added to the wait list every 14 minutes. Let that sink in. Over the last few years, donation after cardiac death (DCD) and extended criteria donation (ECD) has increased as an attempt to increase the number of transplants. It remains a Sisyphean task. Should the reluctance of using ODD organs be overcome?

This prospective observational study seeks to fill in the missing variables by assessing these donors, measuring posttransplant outcomes, and organ discard rates.

Methods

Who’s In & Where/When Did They Come From?

The Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR) is a database that includes data on all organ donors, waitlisted candidates, and transplant recipients in the United States.

To record the cause of donor death, the authors collected data from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) Multiple Cause of Death database which has data based on death certificates for US residents.

The study included 337,934 adult deceased-donor organ recipients from 297 transplant centers who were transplanted between January 1, 2000 and September 1, 2017:

177,522 kidney recipients

97,670 liver recipients

35,710 heart recipients

27,032 lung recipients

Who’s Out?

Recipients with missing information on donor mechanism of death (n = 36, 0.01%)

Some more details:

The donor mechanism of death was categorized as one of the following:

Overdose (ODD): drug intoxication

Trauma (TDD): blunt injury, drowning, gunshot, stab wound, asphyxiation, seizure, electric shock, sudden infant death syndrome

Medical (MDD): intracranial hemorrhage, stroke, myocardial infraction, natural causes, other

Overdose Death Rates

Annual age-adjusted rates of overdose deaths calculated using CDC cause-of-death codes

Characterization of Donors

138,565 deceased donors with at least 1 organ recovered characterized as ODD, TDD, and MDD

Donor hospital and residential ZIP codes used to determine state and census region

The Statistical Plan

Outcome: 5 year death-censored graft survival and patient survival

Analysis: Crude and adjusted patient & graft survival by donor type. Adjustment was done using regression to estimate probability of receipt of ODD, and then using propensity score matching with the inverse probability weighting method.

Funding Source: Various NIH grants, via NCI, NIAID and NIDDK.

Results

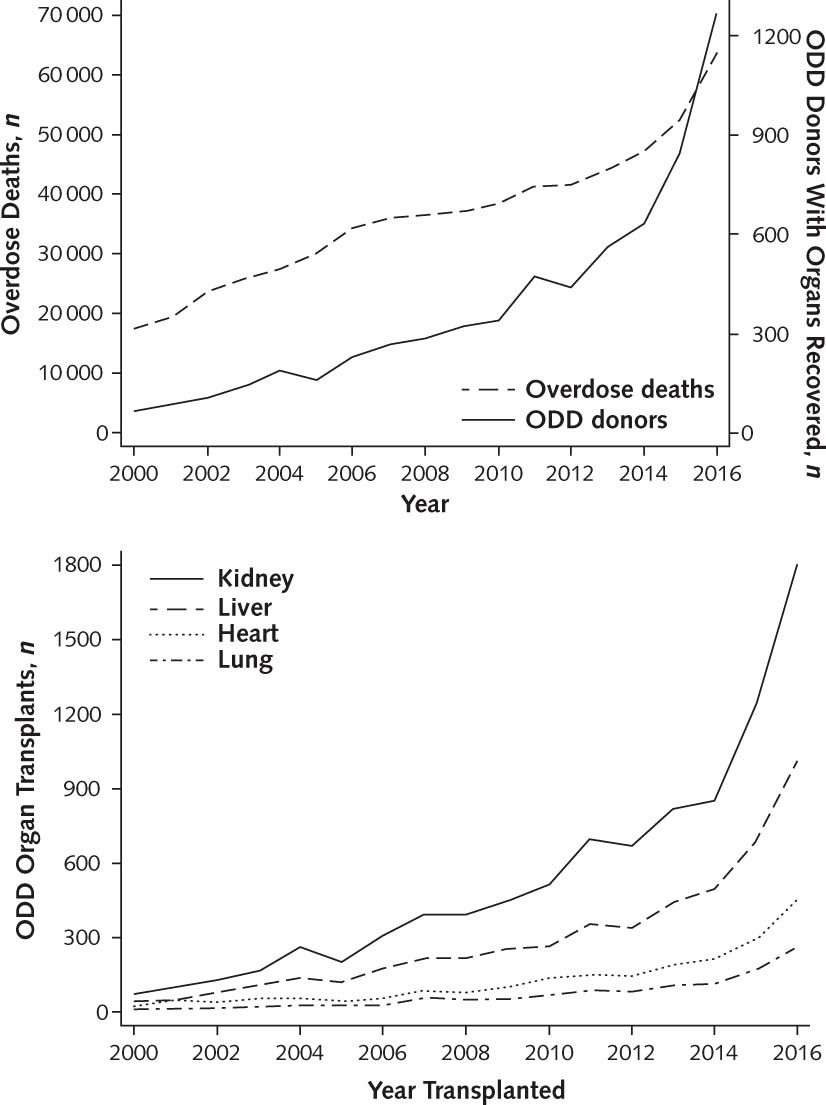

The authors found 7313 ODDs between 2000 and 2017, with the number increasing 17% per year. 149 ODD organs were transplanted in 2000 compared with 3533 in 2016. 19,897 ODD organs were transplanted during the study period. Of these organs, 52% were kidneys, 29% livers, 12% hearts, and 7% lungs.

Figure 1. Durand C, et al. Ann Intern Med 2018

From 2000 to 2016, the percentages of ODDs increased. While 15 states had 0 ODDs in 2000, ODDs accounted for at least 10% of donors in 29 states in 2016. The age-adjusted overdose death rate (per 10,000 persons) similarly increased, with the highest rate by state increasing from 15 to 52, in 2000 and 2016, respectively.

Figure 2. Durand C, et al. Ann Intern Med 2018

ODDs were more likely to be/have:

From the Northeast or Midwest

White, age 21-40y

Positive for HCV antibodies

Labeled as IRDs

Donated after cardiac death

History of previous hypertension, diabetes, or previous myocardial infarction (compared to TDD)

Higher serum creatinine levels

Biopsy of kidney (compared to TDD)

ODDs were less likely to have:

History of hypertension, diabetes, or previous myocardial infarction (compared to MDD)

Table 1. Durand C, et al. Ann Intern Med 2018

The prevalence of HCV infection did not change significantly over time among TDDs and MDDs, but did increase among ODDS (7.8% in 2000 vs 30% in 2017). Though the percentage of IRDs increased among ODDs, TDDs, and MDDs, this increase was highest among ODDs (31.4% in 2005 vs 71.8% in 2017).

Figure 3. Durand C, et al. Ann Intern Med 2018

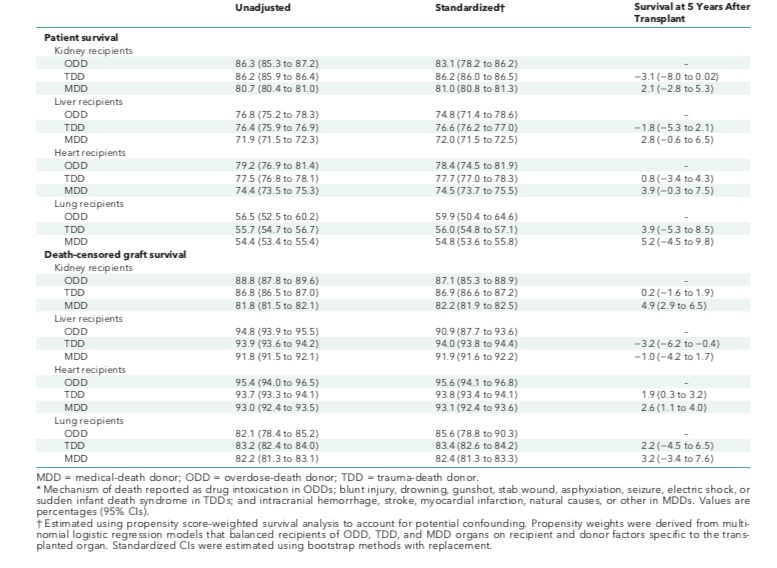

ODD recipients of any organ type had a standardized absolute risk difference in overall survival and death-censored graft survival at 5 years after transplant within 5% of TDD and MDD recipients.

Table 2. Durand C, et al. Ann Intern Med 2018

The discard rates for ODD kidneys and livers was significantly higher after standardization for donor factors (age, sex, race, BMI, HTN, diabetes, DCD, creatinine, and year of donation). After additional standardization for HCV and IRD status, only the liver discard rate remained significantly higher for ODD organs.

Table 3. Durand C, et al. Ann Intern Med 2018

Discussion

Take home message: The dramatic increase of overdoses over the past decade has led to an increase in ODDs in the donor pool, and recipients of these organs have noninferior 5-year graft and overall survival compared to those who receive TDD or MDD organs.

Some limitations of the study: “ODD” included both opioid and nonopioid overdoses, and the authors were not able to document reason for labeling of ODD organs as IRDs.

As the organ waitlist continues to grow, we must strive to safely and optimally utilize available organs. Does this study change your views on overdose-donor organs? Will this change your conversations with potential transplant recipients?

Join us for #NephJC on Tuesday May 22nd or Wednesday May 23rd! All are welcome, looking forward to seeing you there.