#NephJC Chat

Tuesday July 11 9 pm Eastern

Wednesday July 12 8 pm BST, 12 noon Pacific

Perit Dial Int. 2017 Jul-Aug;37(4):362-374. doi: 10.3747/pdi.2017.00018.

Length of Time on Peritoneal Dialysis and Encapsulating Peritoneal Sclerosis - Position Paper for ISPD: 2017 Update.

Brown EA, Bargman J, van Biesen W, Chang MY, Finkelstein FO, Hurst H, Johnson DW, Kawanishi H, Lambie M, de Moraes TP, Morelle J, Woodrow G.

PMID: 28676507 Full Text at PDI

Introduction

Encapsulating Peritoneal Sclerosis (EPS), aka the cocoon, is one of the most feared complications of PD. Thankfully it is quite rare. It has very high mortality and morbidity and nephrologists may sometimes be leery to let someone continue on peritoneal dialysis beyond 5 years in an attempt to avoid this complication. But is this the correct way to do things? Most programs have patients on PD for more than 5 years and some are on PD for more than a decade! The question is whether it is justified in pulling the plug on these patients at a defined moment in time on PD (eg 5 years) to prevent EPS?

This week, NephJC collaborates with ISPD to discuss the recently released (#openaccess) guidelines which attempts to answer this precise question. Joint Host for this chat will be the ISPD 2018 team, lead by Daniel Schwartz.

Before I jump in to write about the guidelines, I will very briefly review the entity itself. There are several excellent reviews published in the last few years and these are linked here and here.

EPS is a clinical syndrome characterized by recurrent small bowel obstruction with nausea, vomiting, abdominal distension, decreased appetite, and weight loss. Occasionally blood stained ascites with fever is seen and there may be increased inflammatory markers. Morphologically there is peritoneal membrane thickening (sclerosis) and calcification with bowel adhesions and/or encapsulation. Historically this is associated with very high morbidity and mortality at nearly 50% within a year of diagnosis. This has prompted some to advocate a time limit on duration of PD to prevent this complication.

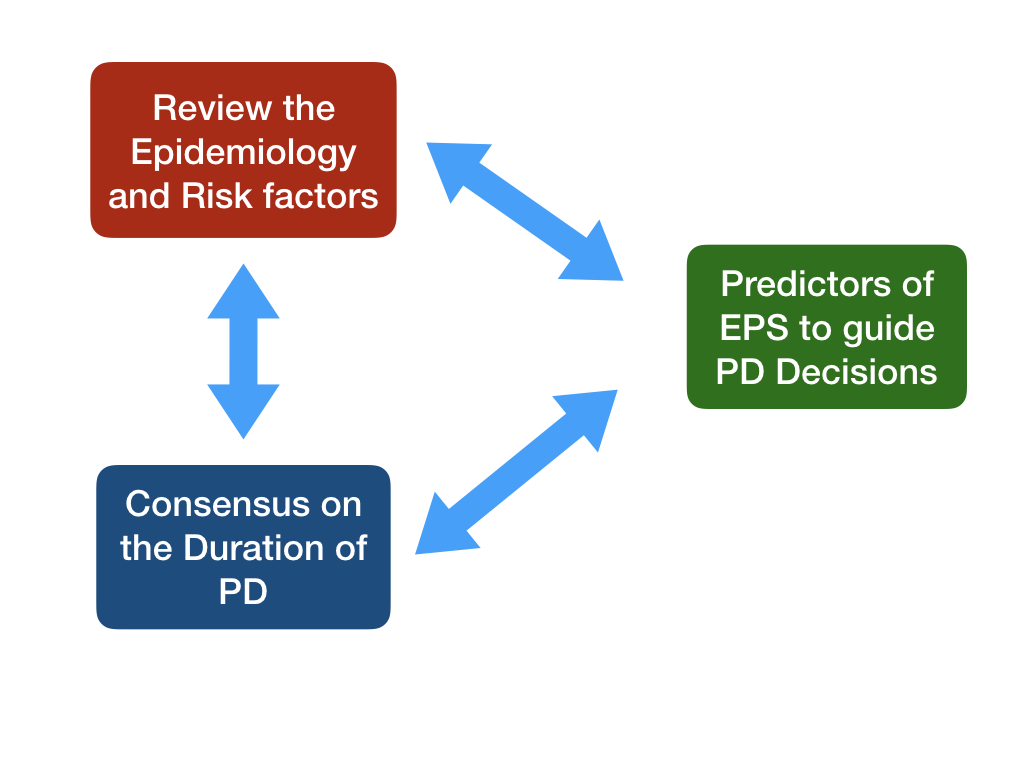

Principal Aims of the Position Paper

There have been guidelines published previously (Japanese, UK, Dutch and previous ISPD statement) which have attempted to explore this question however these were felt to have the following problems by the ISPD work group:

Epidemiology of EPS

Apart from the fact that EPS is very uncommon across all centers, there is a marked variability in the reported incidence and prevalence rates of EPS (see table 1 from paper for details of the literature). The prevalence varies from 0.4% - 8.9% and its incidence is 0.7 – 13.6 per 1000 patient-years. EPS occurs very rarely before 3 years and its incidence even after 5 years on PD is 0.6% to 6.6%. This variability cannot be ignored and can be due to many factors:

Risk Factors

While most reports and studies were consistent in identifying length of time on PD as a risk factor for EPS – there were several other risk factors proposed – including the following – (Caveat : All these data are too imprecise/inconsistent to be considered reliable markers)

Higher dialysate glucose

Conventional PD solutions

Young age

Abdominal surgery

Beta blocker use

Icodextrin use

Kidney Transplant

UF Failure

High peritoneal solute transport rate (PSTR)

Balance: One fact is very elegantly illustrated in the paper - that there must be a very realistic risk assessment before switching “asymptomatic” patients on PD to Hemo to prevent EPS – the alternative risks of HD complications are NOT TRIVIAL! - see figure.

The paper then goes on to review the problems in the clinical aspects of EPS.

Diagnosis

EPS can be diagnosed using a combination of imaging techniques and clinical symptoms of small bowel obstruction. Only a fibrous cocoon encasing the bowels is diagnostic. There are several caveats in the diagnosis of EPS

In majority of patients EPS presents AFTER withdrawing or stopping PD.

EPS may appear up to 5 years after stopping PD , even post Transplant

Long term PD related changes in peritoneum must be differentiated from EPS.

High peritoneal solute transport rate (PSTR) is not exclusive to EPS and can be present in long standing PD patients without EPS.

Management of EPS

Modality switch – Generally PD is stopped and patients transferred to HD, however for mild cases the balance of risks of HD vs continuing PD need to be weighed carefully.

PD Catheter – Is usually removed, while some patients in Japan keep the catheter in situ for regular peritoneal lavage. Again there is not enough data to suggest benefit or risk of this intervention.

Nutrition Support – This is crucial, and many patients may even require parenteral nutrition

Anti-inflammatory therapy: medications like Tamoxifen, steroids and immunosuppression have been reported to be of benefit in case series. Evidence for any of these is not strong and is sometimes contradictory.

Surgical treatment – Expert surgical care in hands of centres and surgeons experienced in EPS surgery has brought down the mortality rate to about 30%.

Renal Tx and EPS – Being on PD is obviously not a contraindication, however it is useful to remember that EPS can occur post Tx especially for those who were on PD for a long time. Early transplant remains a key intervention for improved outcomes irrespective of the dialysis modality.

Screening and predicting EPS

It would be best if there were tests which could predict EPS or detect EPS at an early enough stage for modality switch and early interventions to be administered. However there are no reliable screening tools.

Change in peritoneal solute transport rate is proposed by some, however this change can occur without EPS in long standing PD patients as well. Also PSTR in EPS patients appears in a fairly later stages limiting its application as a screening test/risk factor.

Uncoupling of solute and ultrafiltration – a reduction in osmotically driven water flow (sodium sieving, free water transport or osmotic conductance) has been verified in EPS patients. A 3.86% based modified PET may be useful as this uncoupling suggests development of fibrosis.

CT Scan – Periodic CT scans are also proposed as a measure to identify EPS – however there are reports of EPS developing in a year of a normal CT scan.

Biomarkers – The most consistent biomarkers are inflammatory markers – IL-6, TNF-alpha, MCP-1, Chemokine ligand15, PAI-1 are slightly elevated up to several years before EPS. However the data is not robust to use these as predictive tests.

Individually these screening tests have not been able to reliably predict EPS, however there may be potential in combining these tests to attempt a more reliable risk prediction model.

Prevention of EPS

There is no prospective data on measures which could successfully prevent EPS. The classic situation would be a patient typically failing PD (rising membrane permeability, low UF capacity, difficulty in fluid balance) who would be transitioned to HD – it is not known if this results in increased EPS or modality switch changes the risk of EPS.

Using biocompatible PD fluids has been shown to have less peritoneal membrane fibrosis and vascular sclerosis. Some prospective observational studies have actually shown less EPS with biocompatible solutions and that could be an option.

Competing Risks

It is not possible to ignore the competing risk of death when considering a rare entity like EPS. Several studies have shown that in competing risk prediction model the variability of EPS was explained – “Real World” risk of EPS is almost entirely due to risk of death and the duration of PD.

Conclusion

At the end of this position statement – the authors reiterate that EPS is rare. There is NO evidence to hold PD only to “prevent” EPS. There is NO “optimal time” for PD duration to avoid EPS. Long term patients should be counselled regarding risks and the benefits of remaining on PD or attempting in-center hemodialysis and a shared decision should be made.