#NephJC chat

Tuesday May 23rd 9 pm Eastern

Wednesday May 24th 8 pm BST

Am J Kidney Dis. 2017 Mar 24. pii: S0272-6386(17)30536-X. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2017.01.045. [Epub ahead of print]

Kidney Injury and Repair Biomarkers in Marathon Runners.

Mansour SG, Verma G, Pata RW, Martin TG, Perazella MA, Parikh CR.

PMID: 28363731 (Free Access from AJKD with this link)

Introduction

From Pheidippides in 490 BC, to the present day, there has been a huge increase in running with more than 800 marathons worldwide, with around 500K participants in the United States alone. I have been preparing for one too! Exercise is good for you, right? But could there be some negative consequences of running?

A couple of months back a patient asked me, "Doctor, my 25 year old daughter is running a marathon. She is otherwise healthy. Does she need any additional tests for her kidney function?" Indeed, marathon running is associated with intense physical exertion due to the 26 mile run and heat stress involved. Although blood flow increases significantly to the skeletal muscles and skin during the marathon, renal blood flow may decrease to 25% of rest levels and this may potentially cause ischemic injury to the kidneys. In addition, running long distances increases core body temperature and induces heat stress that may cause kidney damage. The relationship between marathon running and actual kidney injury remains unclear. In the paper from Mansour and colleagues the authors look at the risk of acute kidney injury in marathon runners by using both conventional and novel biomarkers of injury and repair.

Study Design

This is a prospective observational study. Marathon runners participating in the 2015 Hartford Marathon were enrolled via a survey posted on their registration website.

Inclusion criteria:

Runners aged 22 to 63 years and consented for research

BMI of 18.5-24.9 kg/m^2

At least 3 years of training experience

Minimum of 15 miles of training per week for the last 3 years

Completed at least 4 races that were > 20 km in distance

Completed a previous marathon within the last 5 years within 50% to 70% of their World Association of Veterans Athletes performance limit

The criteria were designed to enrich the study with experienced runners, who would be less likely to get rhabdomyolysis, from unaccustomed exercise. Participants were excluded if they had any of the following:

Any major running injuries in last 4 months

Participated in another marathon within 4 weeks prior to the race

Used non steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID’s) within 48 hours prior or 24 hours after the marathon (past usage was acceptable)

Used statins or anabolic steroids

Donated blood within 8 weeks prior to the race

History of hypothyroidism, kidney disorders, coronary artery disease, or convulsive seizure

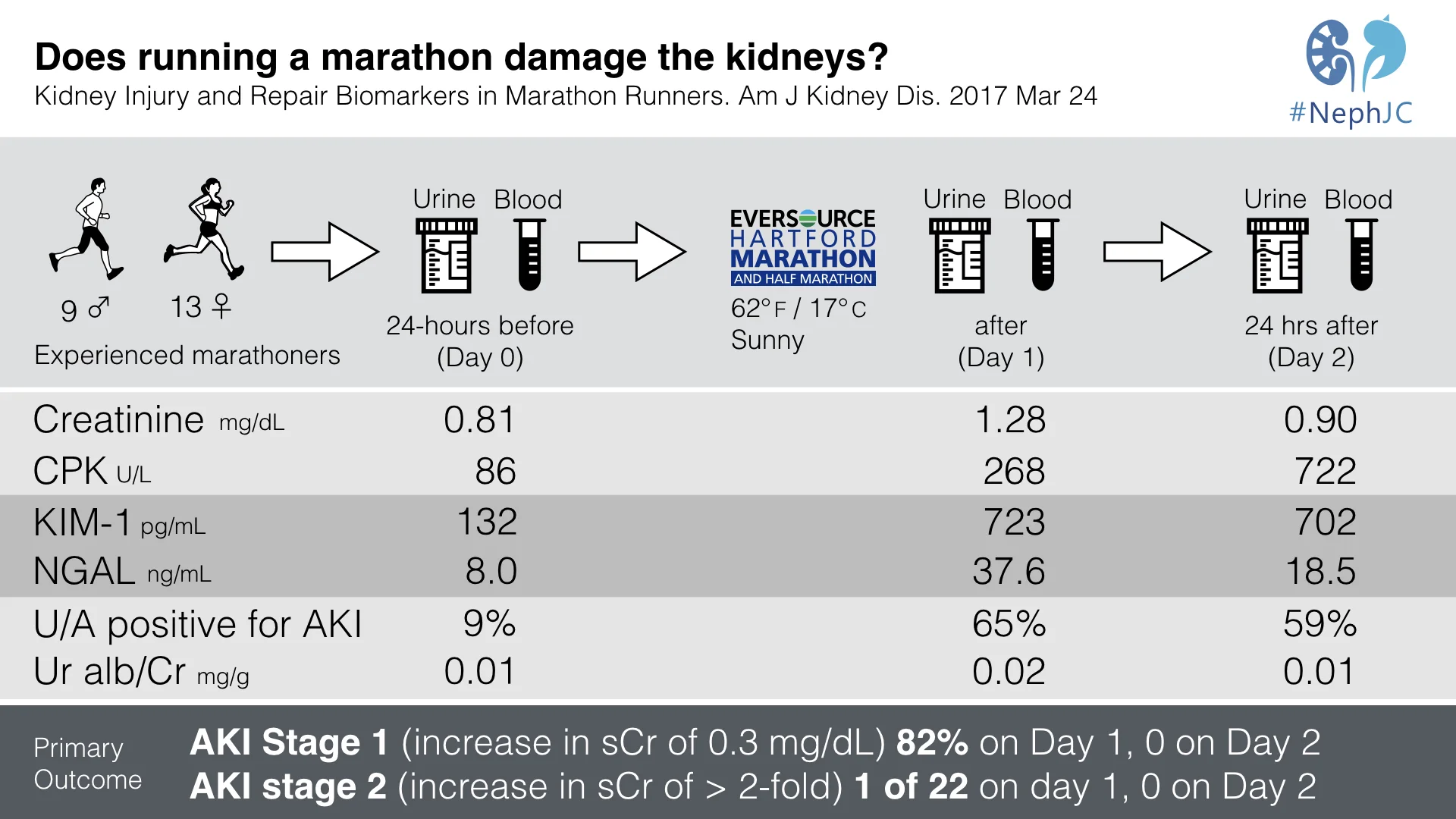

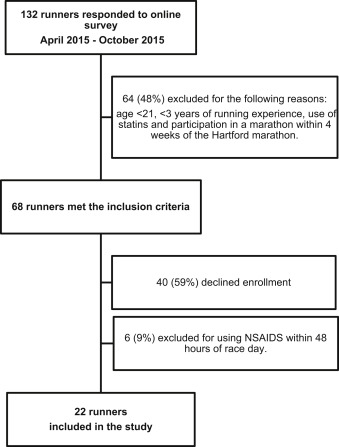

Figure 1 shows the enrollment details of the marathon study cohort.

Figure 1 from Mansour et al, AJKD 2017

Urinary and blood samples were collected at 3 different times:

Day 0 (24 hours pre-marathon, ie actually day -1)

Day 1 immediate post marathon, within 30 minutes

Day 2 post marathon within 24 hours

Serum creatinine and creatine kinase, urine albumin, and urine microscopy were evaluated at these times.

Blood pressure, heart rate, pulse oximetry, and respiratory rate were measured on days 0 and 2. However, due to unclear reasons, on day 1, only heart rate and pulse oximetry were measured.

The biomarkers that were measured at each timepoint were:

Outcomes

There were 3 outcomes of interest, assessed at 3 different time points of day 0, day 1 and day 2.

Acute kidney injury defined by AKIN criteria

Urine microscopy score

Level of kidney injury and repair markers

Stage 1 AKI was defined as 1.5 to 2-fold or 0.3-mg/dL increase in serum creatinine level within 48 hours of day 0. Stage 2 AKI was defined as a 2 to 3-fold increase in serum creatinine. Urine microscopy score was defined by the number of granular casts and renal tubular epithelial cells. Positive urine microscopy findings was defined as a score ≥ 2 on day 1 or 2.

Results

A total of 22 runners were included in the final study cohort. The following significant results were noted:

Mean age was 44 years.

41% were men and 59% were women.

6 (27%) reported NSAID use (within 2 weeks of the race, but not within 48 hours of race day)

50% reported use of herbal supplements.

Cohort characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1 from Mansour et al, AJKD 2017

Vital signs of marathon runners are shown in Table 2.

Table 2 from Mansour et al, AJKD 2017

Serum creatinine concentration peaked on day 1 in all runners (Figure 2). Median creatinine values(Table 3):

Days 0: 0.81 (IQR, 0.76-0.95) mg/dL

Day 1: 1.28 (IQR, 1.09-1.54) mg/dL

Day 2: 0.90 (IQR, 0.80-0.90) mg/dL

Figure 2 from Mansour et al, AJKD 2017

Table 3 from Mansour et al, AJKD 2017

82% developed AKI stage 1, and one runner developed AKI stage 2.

73% had a microscopic diagnosis of AKI on day 1 or day 2.

Serum creatine kinase increased significantly from day 0 to day 2 .

Urine albumin levels significantly increased on day 1.

Biomarker Results

Both urinary injury and repair markers peaked at day 1, immediately post marathon. IL-6, IL-8 and KIM-1 had the highest fold increase on day 1.

Table 4, from Mansour et al, AJKD 2017

Figure 4 from Mansour et al, AJKD 2017

Y-axis shows magnitude of how many times increase in biomarker levels compared to baseline on day 0.

Discussion

The study is one of the first prospective studies that aims to look at the risk of kidney injury with use of conventional and novel kidney biomarkers in marathon runners. Even though the majority of patients developed AKI stage 1, it was transient with kidney function nearing baseline on day 2. The same was true for kidney injury and repair biomarkers, that showed a transient increase on day 1, but started trending towards normal on day 2. Blood work was not done on subsequent days, which could have helped to determine the level of recovery of kidney function following marathon running. Interestingly, there was an increase in the levels of creatine kinase on subsequent days likely due to muscle breakdown during running. However, the increase in creatine kinase did not show any correlation with conventional or novel markers of kidney injury/repair.

Limitations

The small sample size of 22 runners and a short follow up of only 48 hours are the major limitations, with unclear implications of these injury markers in this population. What is reassuring is that the 22 marathon runners in this cohort did not have any evidence of any chronic kidney disease in spite of having a median 12 years of running experience. More long term studies are required to test the hypothesis. Till that time, I will continue to run and recommend the same.

Points for discussion

There is a large body of literature showing small changes in creatinine to be associated with long term adverse outcomes. How does this study fit into that literature?

If this evidence of kidney injury is significant, can anything be done to ameliorate it, short of not running marathons? Should there be a minimum period between two marathons, or should we check for recovery in between?

Summary prepared by Silvi Shah

The chats were quite something. We sprinted through a lot of tweets in one hour each. Authors Chirag Parikh and Sherry Mansour joined us for first chat, and Sherry returned for the second chat too! Storifies below curated by Hector and Ben.