#NephJC Chat

Tuesday February 28th, 9 pm EDT

Wednesday March 1st 9 pm IST

Circulation 2022 Dec 6;146(23):1735-1745.

doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.121.054990. Epub 2022 Nov 6.

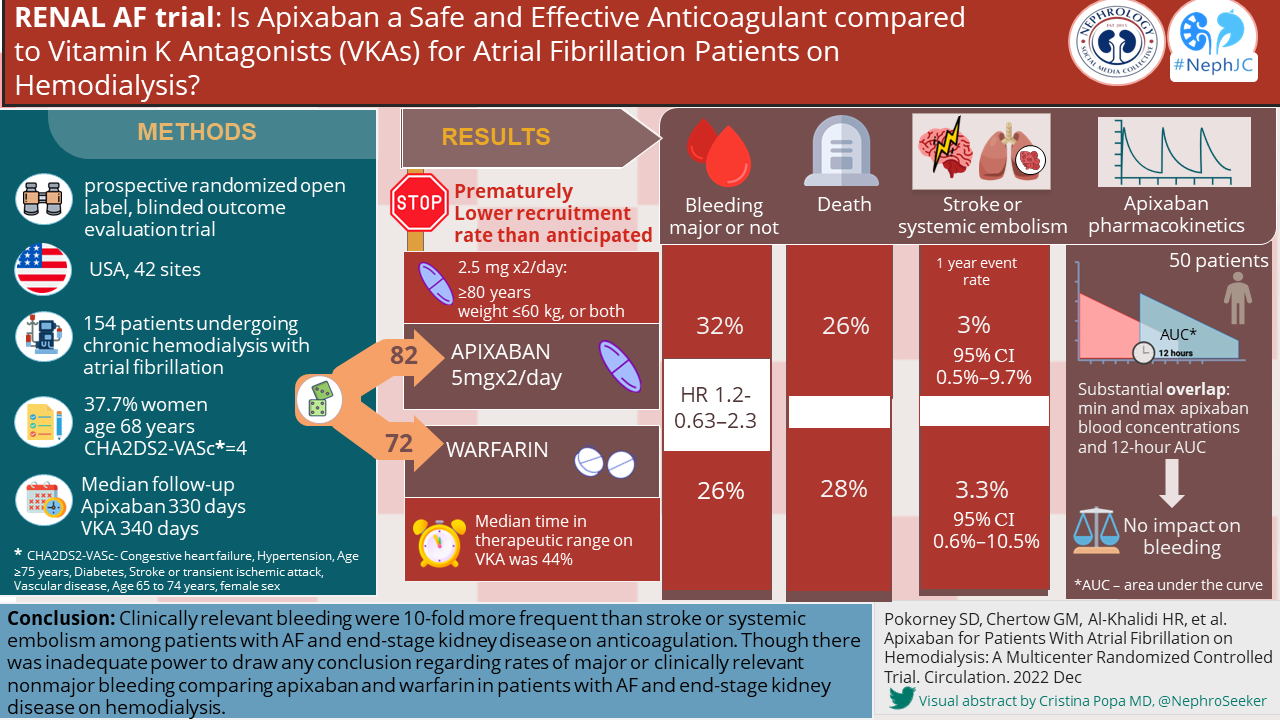

Apixaban for Patients With Atrial Fibrillation on Hemodialysis: A Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial

Sean D Pokorney, Glenn M Chertow, Hussein R Al-Khalidi, Dianne Gallup, Pat Dignacco, Kurt Mussina, Nisha Bansal, Crystal A Gadegbeku, David A Garcia, Samira Garonzik, Renato D Lopes, Kenneth W Mahaffey, Kelly Matsuda, John P Middleton, Jennifer A Rymer, George H Sands, Ravi Thadhani, Kevin L Thomas, Jeffrey B Washam, Wolfgang C Winkelmayer, Christopher B Granger; RENAL-AF Investigators

PMID: 36335914

AND

Circulation 2023 Jan 24;147(4):296-309.

doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.122.062779. Epub 2022 Nov 6.

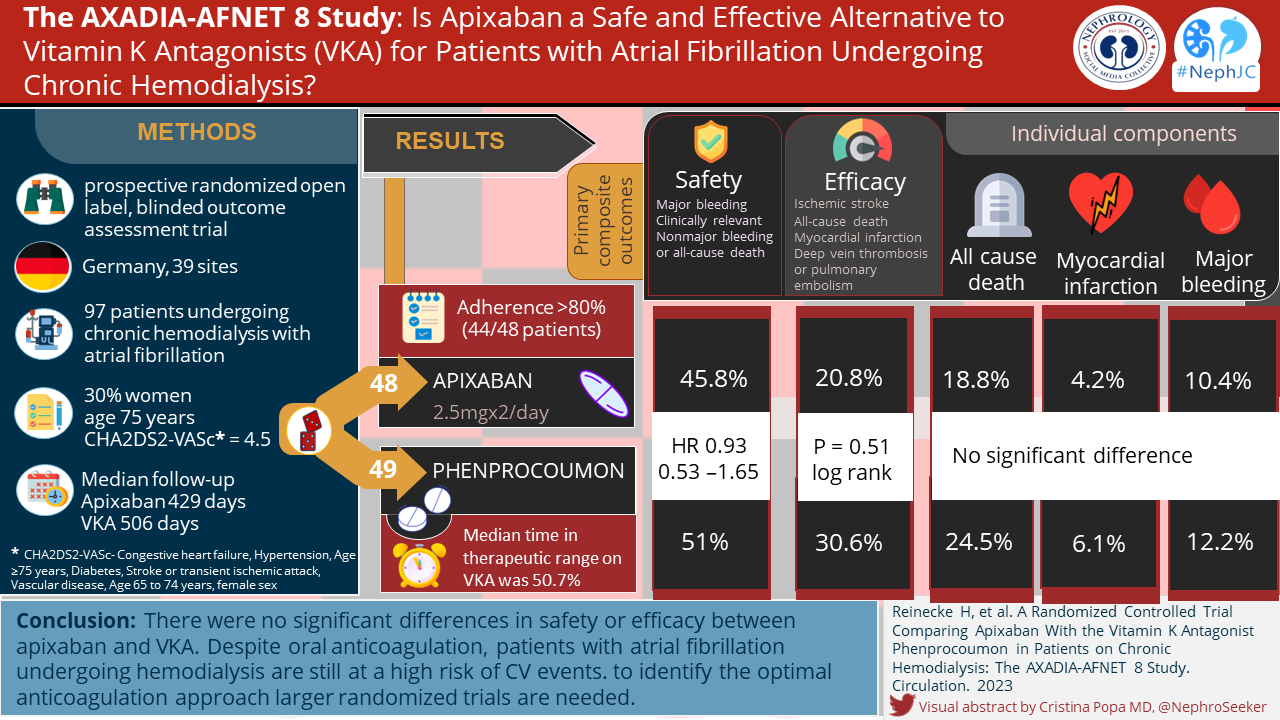

A Randomized Controlled Trial Comparing Apixaban With the Vitamin K Antagonist Phenprocoumon in Patients on Chronic Hemodialysis: The AXADIA-AFNET 8 Study

Holger Reinecke, Christiane Engelbertz, Rupert Bauersachs, Günter Breithardt, Hans-Herbert Echterhoff, Joachim Gerß, Karl Georg Haeusler, Bernd Hewing, Joachim Hoyer, Sabine Juergensmeyer, Thomas Klingenheben, Guido Knapp, Lars Christian Rump, Hans Schmidt-Guertler, Christoph Wanner, Paulus Kirchhof, Dennis Goerlich

PMID: 36335915

Introduction

Bringing out the rat poison for anticoagulation in atrial fibrillation (AF) seems a far cry from the precision medicine we aspire to in 2023. But as usual, the dialysis world is lagging behind the rest of medicine, despite an atrial fibrilation prevalence of ~12% and a 2-3-fold higher risk of stroke and mortality with AF than in those without AF (Zimmerman et al, NDT 2012). The role for anticoagulation in patients at high risk of thromboembolism without advanced kidney disease is very clear. Over recent years, in patients with eGFR >25 ml/min, vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) have been superseded by direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) such as factor Xa inhibitors due to better safety and efficacy profiles and convenience of administration (ARISTOTLE trial, Granger et al,NEJM 2011). Registry data from the US also shows increasing use of apixaban for this indication in patients with end stage kidney disease (ESKD) - we have discussed a study based on these in the past.

Unsurprisingly, patients with ESKD have been routinely excluded from these large practice-changing trials in AF and, unfortunately, ARISTOTLE's philosophy may not extend to this category of patients. Patients with ESKD have different risks of both systemic thromboembolism and bleeding compared to the rest of the population. Differences in the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles of these medications in advanced kidney disease alter their risk-benefit-ratios. For example, many DOACs are renally excreted, and therefore accumulate in ESKD. On the other hand warfarin is associated epidemiologically and mechanistically with vascular calcification and calciphylaxis in ESKD. Therefore, despite FDA approval for the use of apixaban in ESKD based on pharmacokinetic data, the results of clinical outcomes from the trials in patients without ESKD are not generalizable to ESKD.

DOACs are a popular alternative to VKAs for several reasons tabulated below; apixaban has the added advantage, compared to other DOACs, that it is mostly non-renally eliminated and therefore an attractive option in ESKD.

Late 2022 saw the release of not one, but two randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing oral VKAs and apixaban, an oral factor Xa inhibitor, (hence the “xa” in the middle of its name), on safety and efficacy outcomes in patients with atrial fibrillation and ESKD. These were RENAL AF (Pokorney et al, Circulation, 2022) and AXADIA-AFNET 8 (Reinecke et al, Circulation, 2022), reviewed here.

Observational data

In a retrospective cohort study (N= 25,523) (Siontis et al, Circulation 2018), which we discussed before, warfarin and low-dose apixaban (2.5 mg bid) were not beneficial as compared ‘normal’ dose apixaban (5 mg bid). This raises questions regarding the efficacy of the lower dose of apixaban in preventing thromboembolic endpoints, which we will see was used in the AXADIA-AF NET 8 Trial. However, confounding by baseline characteristics and selection bias are potential pitfalls in observational studies.

There have been concerns about increased bleeding in dialysis patients with AF started on DOACs, compared to warfarin. This has been a particular consideration for drugs with primarily renal elimination such as dabigatran and rivaroxaban. (Chan et al, Circulation 2015) Because apixaban is largely cleared by hepatobiliary excretion, it should have a better safety profile than other DOACs in ESKD.

RCTs of DOACs for AF in ESKD

There has been one published multi-arm randomized controlled trial of VKA vs. rivaroxaban vs rivaroxaban plus vitamin K2 in 132 patients on hemodialysis at 3 sites in Belgium (VALKYRIE, De Vriese et al, JASN 2021). The primary end point of fatal or non-fatal cardiovascular events occurred at a rate of 63.8 per 100 person-years in the VKA group, 26.2 per 100 person-years in the rivaroxaban group, and 21.4 per 100 person-years in the rivaroxaban plus vitamin K2 group. After adjustment for competing risk of death, the hazard ratio for life-threatening and major bleeding with rivaroxaban was 0.39 (95% CI, 0.17-0.90; P=0.03), and 0.48 (95% CI, 0.22-1.08; P=0.08) with rivaroxaban plus vitamin K2 and 0.44 (95% CI, 0.23-0.85; P=0.02) in the pooled rivaroxaban groups. Though the results are optimistic, small sample size with 25% premature discontinuation of treatment and subtherapeutic warfarin (<16% had target INR 60% of the time) cast doubt on the results.

There were no RCTs of apixaban in ESKD… until now.

The Studies

A Tale of Two Trials

Two trials came out in Circulation in late 2022. RENAL AF and AXADIA-AFNET 8 Study. (Pokorney et al, Circulation, 2022; Reinecke et al, Circulation, 2022). Both trials were RCTs designed to test non-inferiority of apixaban vs. standard VKAs. A deep discussion into the intricacies of non-inferiority trials can be found here.

The premise behind using a non-inferiority design to assess safety in these two trials is that clinicians and patients may be willing to accept a small increase in bleeding events in return for the other possible advantages of using direct factor Xa inhibitors. While both trials looked into efficacy outcomes as well, they were not adequately powered for these endpoints.

Unfortunately, because RENAL AF recruited way below its target, its results remain exploratory and cannot be considered definitive. The table below compares the study designs of RENAL AF and AXADIA-AFNET 8.

*Exclusion criteria: moderate or severe mitral stenosis, ongoing need for aspirin >100mg daily, aspirin with P2Y12 antagonist therapy, oral anticoagulation for a reason other than AF, life expectancy <3 months, or anticipated kidney transplant within the next 3 months.

#Exclusion criteria: stroke within 3 months of enrollment, hemodialysis for <3 months, moderate or severe aortic or mitral stenosis, conditions other than AF requiring anticoagulation, active endocarditis, planned AF or flutter ablation, serious bleeding <6 months before enrollment, uncontrolled diabetes, history of cancer, or need for chronic aspirin therapy.

Outcome definitions

Major bleeding was defined as per the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (Shulman et al, J Thromb Haemost 2005)

Fatal bleeding, and/or

Symptomatic bleeding in a critical area or organ, such as intracranial, intraspinal, intraocular, retroperitoneal, intra-articular or pericardial, or intramuscular with compartment syndrome, and/or

Bleeding causing a fall in hemoglobin level of 20 g/L (1.24 mmol/L) or more, or leading to transfusion of two or more units of whole blood or red cells.

Clinically relevant non-major bleeding was also defined as per the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis. (Kaatz et al, J Thromb Haemost 2015). Any sign or symptom of hemorrhage (e.g., more bleeding than would be expected for a clinical circumstance, including bleeding found by imaging alone) that does not fit the criteria for the ISTH definition of major bleeding but does meet at least one of the following criteria:

requiring medical intervention by a healthcare professional

leading to hospitalization or increased level of care

prompting a face to face (i.e., not just a telephone or electronic communication) evaluation

Knotted in Nots: Testing a non-inferiority hypothesis

With appreciation of the challenges in recruitment, there are some concerns about the trial design of AXADIA-AFNET 8. While including all-cause mortality may increase the number of events in a trial, unless they are directly related to the intervention they will tend to dilute differences in treatment effect, and the result will trend towards the null, i.e. non-inferiority. In this case, this could naturally lead to a “positive” trial result. Rather oddly, all cause mortality was included in the secondary composite efficacy outcome as well, further blurring the outcome interpretation.

Intention to treat analysis, the standard of the superiority trial, can also fall short in non-inferiority design where non-adherence, subtherapeutic treatment, and patient withdrawal all decrease treatment differences in the two groups and bias towards non-inferiority. In both these trials VKA use was below target therapeutic range more than half the time, rendering the standard of care arm below standard, and perhaps magnifying the therapeutic effect of apixaban. Of course, one may argue that in a trial setting this may actually reflect better therapeutic targets than in general practice, and is one of the challenges of using VKA in the “real world”. Inadequate warfarinisation has been problematic in other VKA trials in ESKD, (De Vriese et al, JASN 2021) and could be one of the reasons for the lack of clarity on efficacy in this group. In AXADIA-AFNET 8 a prespecified per protocol analysis was consistent with the ITT analysis. Here too, per protocol was considered having received a single dose of the treatment, and therefore does not reflect sustained anticoagulation.

In AXADIA-AFNET 8, two primary statistical null hypotheses were planned to be tested hierarchically with respect to the primary safety outcome. The margin for non-inferiority was set at a HR of 1.25, i.e. a HR <1.25 would reject the null hypothesis and be considered proof of non-inferiority of apixaban. Further testing for superiority (HR <1) would be done only if the treatment was proven non-inferior.

In this trial there was an assumption that apixaban would be safer than VKA, with a HR for the primary outcome of 0.61. This allowed them to project that 64 events would give them 80% power to demonstrate non-inferiority at a margin of 1.25.

Unfortunately, both trials had difficulties in recruitment which portends poorly for future RCTs in this area. One issue in RENAL AF was the reluctance of physicians to enroll patients into the trial based on the need to be started on anticoagulation. In RENAL AF the target sample size was reduced from 760 to 230 patients due to concerns of feasibility and funding. Eventually, the investigators and funder terminated enrollment at 154 patients due to further challenges with enrollment. Difficulties in enrollment are also evident when looking at the recruitment of AXADIA-AFNET 8 which used 39 centers, for 97 patients, eventually falling short of their target number of events of 64.

Apixaban dosing

The FDA guidance on apixaban dosing in ESKD is drawn from a single pharmacokinetic study using 8 patients on HD and 8 healthy subjects who demonstrated comparable maximum blood concentrations and antifactor Xa activity on apixaban 5 mg. (Wang et al, Clin Pharmacology 2015). AXADIA-AFNET 8 used a lower dose of apixaban than is currently FDA approved for patients on HD. This would be expected to lead to lower safety outcomes, the primary outcome of the trial, and a more conservative estimate, trending towards non-inferiority. In view of observational data which does not show efficacy over warfarin with half-dose apixaban, one might question the suitability of a trial of low dose apixaban versus warfarin.(Siontis et al, Circulation 2018)

RENAL AF additionally included a pharmacokinetic (PK) sample analysis component. This required PK samples drawn on day 1, between day 3-5 and on day 28 on 50 patients randomized to apixaban, both pre and post dialysis. Apixaban was to have been administered at least two hours prior to the HD session. The aims behind the measurements at each time point were to demonstrate the following:

Day 1- single dose estimation of apixaban clearance

Day 3-5- Accumulation

Day 28- Steady state exposure

Pre HD- Intrinsic clearance

Post HD- clearance with HD

Apixaban exposures in the steady state were estimated using a 12-hour area under-the curve (AUC0-12), calculated on the day prior to HD, on the last day of the long break, (eg. on Sunday, for a patient on dialysis on Monday/Wednesday and Friday). This was to identify maximum blood levels, as a safety assessment. The data was combined with PK data from the ARISTOTLE trial (Granger et al,NEJM 2011) extending their model to dialysis patients. This study did not measure factor Xa activity.

Results

The baseline characteristics of the RENAL AF trial are shown in the following table. Despite stratification by prior OAC use, there seem to be far more treatment naive patients in the apixaban arm. This could suggest a higher risk for bleeding and/or poor tolerance or adherence in this group.

Baseline characteristics Table 1 from Renal AF.

In AXADIA-AFNET 8, baseline characteristics were broadly similar.

Baseline characteristics Table 1 from ADAXIA-AFNET 8

Overall trial outcomes of RENAL AF and AXADIA-AFNET 8 are summarized in the table below. The low time in therapeutic range (TTR) for warfarin in both trials is similar to what has been seen in other studies in ESKD. As the primary outcome in both trials was a safety outcome, it does raise concerns that the reduced drug dosing may have biased the results in favor of warfarin.

As discussed earlier, the RENAL AF data is mostly exploratory and cannot be used to draw conclusions. Interestingly, bleeding episodes were high with 9 (11%) major bleeding events in the apixaban group and 7(10%) in the warfarin group. Hemodialysis access site bleeding events were responsible for the majority of the clinically relevant non-major bleeds in both the apixaban (10 of 14, 71%) and warfarin (6 of 10, 60%) group. It is worth considering that the spectrum and risk of bleeding events could be quite different in patients on peritoneal dialysis.

The secondary outcome data is summarized in the table below. Secondary (efficacy) outcome events were very few, due to limited recruitment, and broadly similar between the two groups, Only only one ischemic stroke was seen in each arm and no episodes of SE. The median entry CHADS2-VA2Scscore of 4.0, is predictive of 4.8% risk of ischemic stroke in the general population (Friberg et al, EHJ 2012), and 6.4% in patient on HD, based on data from Taiwan (Chao et al, Heart Rhythm 2014) Because of the small numbers of events, the number of patients and event in the study no inferences can be drawn regarding efficacy. There was a higher number of deaths in the apixaban group. Death related to major bleeding occurred in 1 in the apixaban arm and 2 in the warfarin arm. Only one case of intracranial hemorrhage occurred in the study.

Secondary outcomes Table 3 from Renal AF.

Primary outcomes of AXADIA-AFNET 8 (Table 2 below) using Kaplan-Meier product-limit estimates are graphically displayed in Figure 1 and were analyzed using a Cox proportional hazards regression model that included treatment group and prior warfarin status (experienced versus naïve) as covariates. The composite primary safety outcome occurred in 22 patients (45.8%) on apixaban and in 25 patients (51.0%) on VKA (hazard ratio, 0.93 [95% CI, 0.53–1.65]; P noninferiority = 0.157). There were 11 (11.3%) with major and 19 (19.6%) non-major clinically significant bleeding events, across the trial with no difference between arms. There were no significant differences in all-cause mortality, 18.8% versus 24.5%. The composite primary efficacy outcome occurred in 10 patients (20.8%) on apixaban and in 15 patients (30.6%) on VKA (P=0.51; log rank). Only 1 ischemic stroke occurred (in the VKA arm). Based on observational data, the CHADS2VA2Sc score of 4.5 would have predicted a rate of ischemic stroke at 7 per hundred person years (Chao et al, Heart Rhythm 2014), which was 1% in AXADIA AF NET while on anticoagulation. The authors concluded that no differences were observed in safety or efficacy outcomes, a bold conclusion to make from an underpowered non-inferiority trial.

Outcomes, Table 2 from ADAXIA-AFNET 8

Kaplan-Meier curves for safety and efficacy outcomes analyzed by intention to treat and on-treatment. Figure 1 from ADAXIA-AFNET 8

Pharmacokinetic Analysis of RENAL AF

The PK data of RENAL AF was consistent with the results of ARISTOTLE and were used to extend their model. (Figure 2 & 3 below). The median steady state 12-hour AUC 0-12 were 2,475 ng-h/mL (10th-90th percentiles 1,342-3,285) and 1,269 ng-h/mL (10th-90th percentiles 615- 1,946) for patients who received the 5 mg and 2.5 mg BID, respectively. The AUC 0-12 for the 5 mg dose in RENAL-AF were comparable with the AUC0-12 for patients with estimated creatinine clearance (eCrCl) by Cockroft-Gault of 45-59 mL/min (median 2,101ng/mL*hr), 30-44 mL/min (median 2,402 ng/mL*hr), and 15-29 (median 2,781 ng/mL*hr) from the ARISTOTLE trial. However, the AUC 0-12 for the 5 mg dose in RENAL-AF was nearly two-fold that of patients with normal renal function (eCrCl ≥ 90 mL/min) (median 1,374 ng/mL*hr) from the ARISTOTLE trial. The AUC for the 2.5 mg dose in RENAL-AF did not differ from the AUC for patients with eCrCl ≥ 15 and < 90 mL/min from the ARISTOTLE trial, and was about half that of the 5mg dose.

Figure 2 from Renal AF.

Figure 3 from Renal AF.

The results were timely for AXADIA-AFNET 8, which used the lower 2.5mg dose in the standard arm. They argue that pharmacokinetic data from RENAL AF support their choice of 2.5mg BID in ESKD patients on HD, which achieves similar AUC 0-12 (1269 ng/mL*hr) to as 5 mg BID in persons with normal kidney function (1374 ng/mL*hr). In light of the high numbers of bleeding outcomes in both trials, the choice of the lower dose seems justified.

Discussion

Non-inferior to … nothing?

A prerequisite of a clinically meaningful non-inferiority trial is that the control arm has proven treatment effect compared to placebo in the population under question. What do we know about anticoagulation for AF in ESKD? None of these RCTs had a ‘no treatment’ arm. Unfortunately, when it comes to VKA being accepted as standard of care for AF in ESKD, the waters are still quite muddy and data is both observational and conflicting. (Bhatia et al, Clinical Cardiology 2018). This was sussed out in a meta analysis by Van Der Meersch et al (Am Heart J 2017) including data from 12 prospective and retrospective observational studies. The results were unpromising with a nonsignificant 26% reduction of the risk of ischemic stroke (HR 0.74; 0.51-1.06), a 21% increase in total bleeding risk (HR 1.21; 1.03-1.43), with no effect on mortality (HR 1.00; 0.92-1.09) with VKA treatment compared to no treatment. They argued that low CHADS2-VA2Sc scores and underdosing of VKA may have blunted therapeutic efficacy. However, the risk of bleeding remains high, and in the absence of randomized controlled trial data, the jury is still very much out on this topic.

So are we anywhere closer to the answer?

The main objectives of both these trials was to assess safety outcomes with apixaban treatment in ESKD. Both had high numbers of bleeding events approximating 30% in both arms. A fair proportion of these were access related bleeding, and considering the burden of stroke might be a reasonable trade off if benefit can be proven. The occurrence of ischemic stroke in both these studies was lower than predicted by CHADS2VA2Sc scoring, and may support efficacy. The pharmacokinetic data from RENAL-AF is valuable and, particularly in this group at high risk of bleeding, informs the use of a lower dose of apixaban in HD patients, without an expected loss of potential benefit.

Both trials were disappointing in that they were not adequately powered to yield a conclusive result. This was partly due to difficulties in recruiting, and difficulties in maintaining and achieving therapeutic anticoagulation in the VKA arm. Hopefully, these challenges can be used to inform the design and conduct of future trials in this area. In the absence of a proven positive risk/benefit of VKA in this group, a non-inferiority trial for safety or efficacy does feel a bit like putting the cart before the horse. Currently trials to assess the efficacy and safety of VKA, apixaban in AF in ESKD are underway:

DANWARD (HD, N= 718), examining warfarin (INR 2-3) versus no treatment

SACK (CKD 5 non-HD or HD, N=1400) examining apixaban 2.5mg bid vs No treatment

SAFE-D (ESRD on HD or PD, N=151) examining warfarin (INR 2-3) vs Apixaban 5mg bid vs No treatment

The inclusion of a “no treatment” comparator in all of these will hopefully clarify the role of anticoagulation in this group. We can certainly hope that if recruitment to these trials can be successfully achieved, we may have an answer to some of these important clinical questions soon.

Summary prepared by Dilushi Wijayaratne

Consultant Nephrologist, Department of Clinical Medicine

University of Colombo, Sri Lanka

NSMC Faculty

Reviewed by Jade Teakell, Jamie Willows, & Cristina Popa

Header Figure created by Evan Zeitler with Midjourney