#NephJC Chat

Tuesday January 16 9 pm Eastern

Wednesday January 17 8 pm BST, 12 noon Pacific

J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017 Nov 7. pii: S0735-1097(17)41519-1. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.11.006. [Epub ahead of print]

2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ ABC/ACPM/ AGS/ APhA/ASH/ASPC/ NMA/ PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical PracticeGuidelines.

Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE Jr, Collins KJ, Dennison Himmelfarb C, DePalma SM, Gidding S, Jamerson KA, Jones DW, MacLaughlin EJ, Muntner P, Ovbiagele B, Smith SC Jr, Spencer CC, Stafford RS, Taler SJ, Thomas RJ, Williams KA Sr, Williamson JD, Wright JT Jr.

PMID: 29146535

Check the Guideline Hub at the ACC/AHA website for links to summary, all the documents, slidesets and more (including links to their guidelines app)

Update: Both the NEJM and Annals have published editorial really disliking these guidelines. The Annals commentary is written by the ACP group, known to be hostile to SPRINT. The NEJM commentary is more balanced, written by Drs Bakris and Sorrentino, and takes particular issue with the 130/80 for low risk, discussed below (2).

Introduction

We riff on our own headline for SPRINT (Is 120 the new 140?) - and for a good reason. Check out the author list for SPRINT vs the new guidelines and tally up the overlap - SPRINT is indeed the big driver of change in this document. It also follows that the reaction to these guidelines parallels the reaction to the SPRINT publication. Gina Kolata covered it for the New York Times, and, also in the NYT, Aaron Carroll predictably thinks it could lead to harm (both $ NYT links). Will they lead to better blood pressure control and lower cardiovascular disease for all of humanity - or will they turn most of us into diseased pill poppers? Let's try to keep the rhetoric away and look at the science and implications of these guidelines for the next #NephJC chat. Given the sheer breadth of the scientific review and recommendations (39 page systematic review, 114 page executive summary, 283 page data supplement - even the slideset with 98 slides), we will focus on a few key aspects for the chat:

The BP recommendations for chronic kidney disease

Management of hypertensive crises

BP target for low risk individuals?

Methods

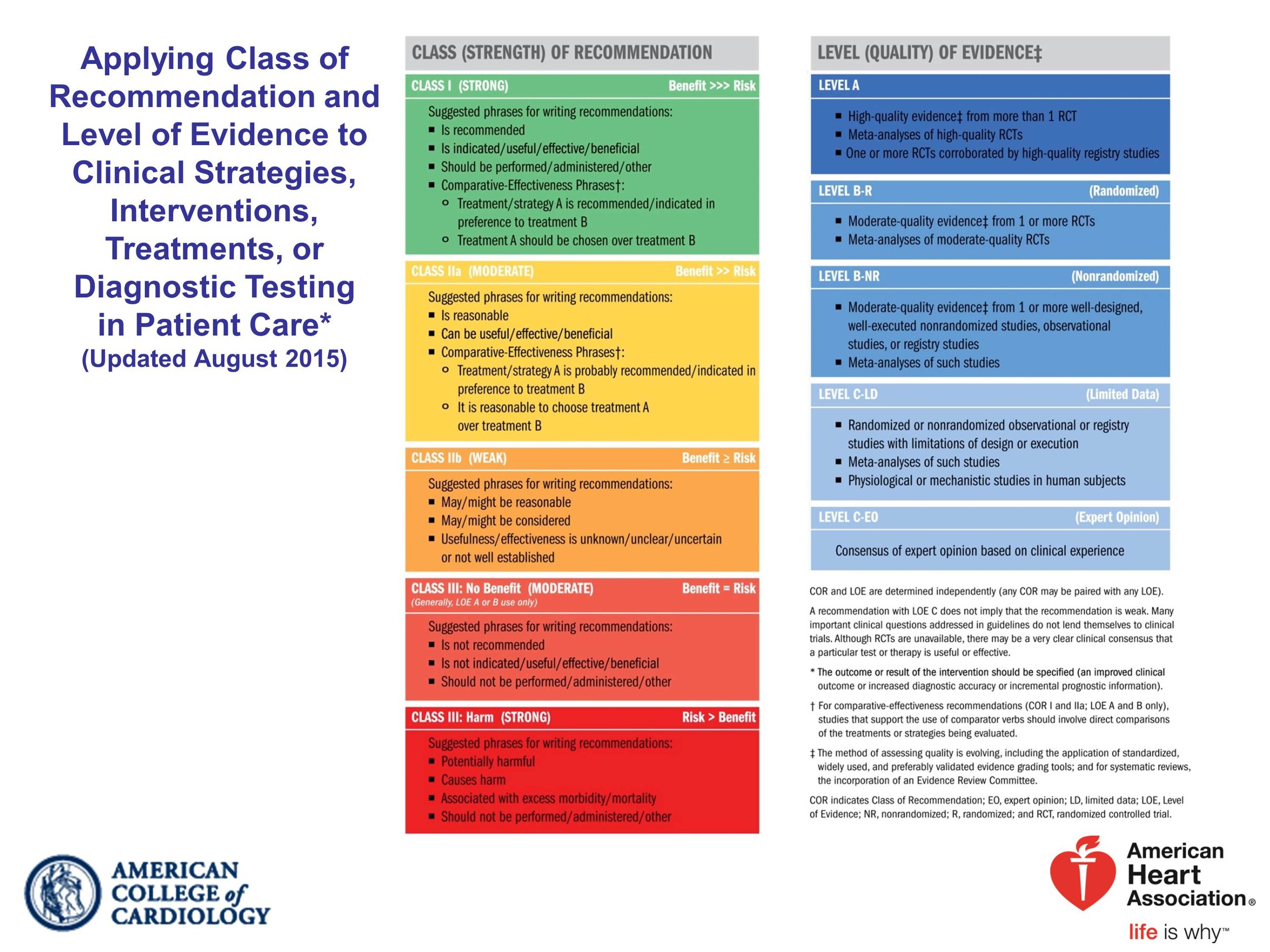

This is the first hypertension guideline produced by the ACC/AHA: taking over this task from the Joint National Committee (JNC) - same as what happened with ATP and cholesterol a few years ago. For this task, the ACC/AHA engaged a gaggle of other professional societies. Strangely the ASN, the AAFP, the ACP and the ACEP were not part of the guideline. The AHA/ACC policy doesn't allow a certain level of conflicts - check out the full set of disclosures for all the writing group at this PDF link. They use this scale to grade the guidelines:

The overall purpose was 'to be comprehensive but succinct and practical in providing guidance for prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high BP'. Let us review whether this promise has been fulfilled.

Results

Blood Pressure measurement

Check out the #NephMadness coverage of the BP measurement method used in SPRINT - automated oscillometric BP, which is considered different - and the reason why the Europeans famously voted thumbs down on SPRINT. Indeed, hypertension purists will continue to protest for the infallibility of the gold standard, ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM). This is what the ACC/AHA guidelines comment on BP measurement (pages 27 to 38):

measure BP properly (with no specific recommendation for manual/automated devices)

Out of Office BP recommended for diagnosis and adjustment of BP meds (either home or ambulatory is acceptable). See table below for comparative BP with different methods:

As has already been pointed out, this table is perplexing on providing home and clinic BP equivalent numbers for nocturnal BP on ABPM. Not all individuals have a BP that dips at night - and this is one of the major strengths of doing an ABPM. The references provided also do not source where these numbers came from - since we know there is a large variation between methods.

There is a nice discussion of masked and white coat hypertension, and we are sure you will prefer the #NephMadness table (below) rather that their table 12:

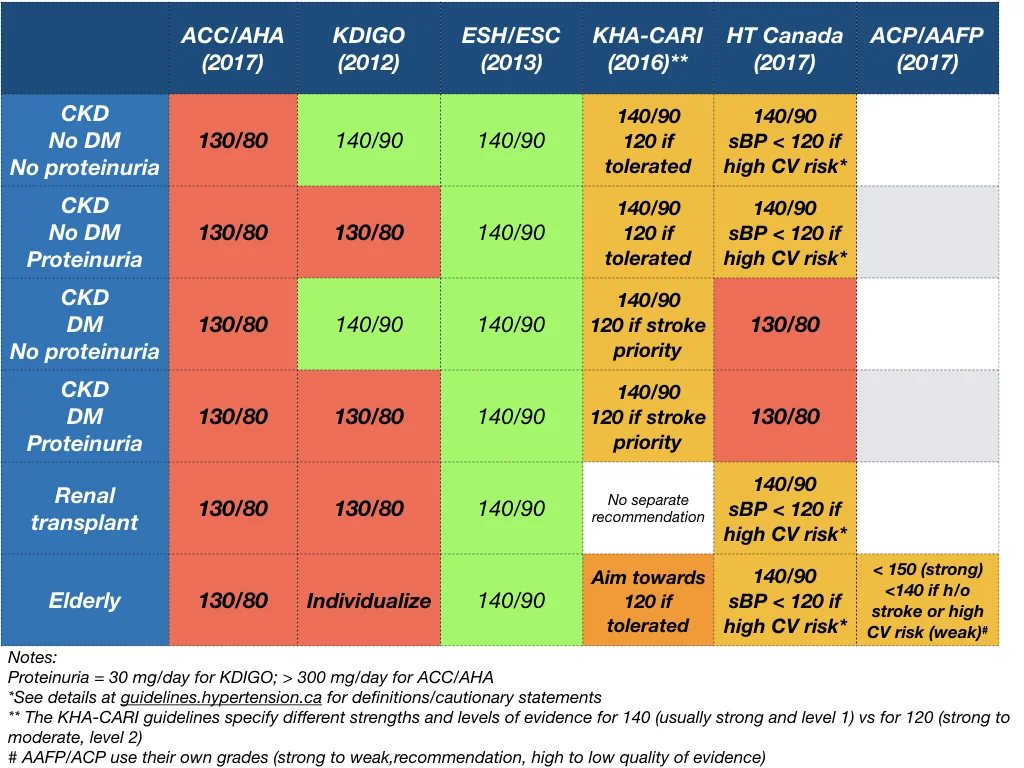

Blood Pressure targets for Chronic Kidney Disease

“Hypertension may occur as a result of kidney disease, yet the presence of hypertension may also accelerate further kidney injury; therefore, treatment is an important means to prevent further kidney functional decline.”

(no evidence/citation is presented for that quote, but we do know from NephMadness that the last clause is not completely accurate). Scroll all the way to page 100, section 9.3 for these recommendations:

from Whelton et al, JACC 2017

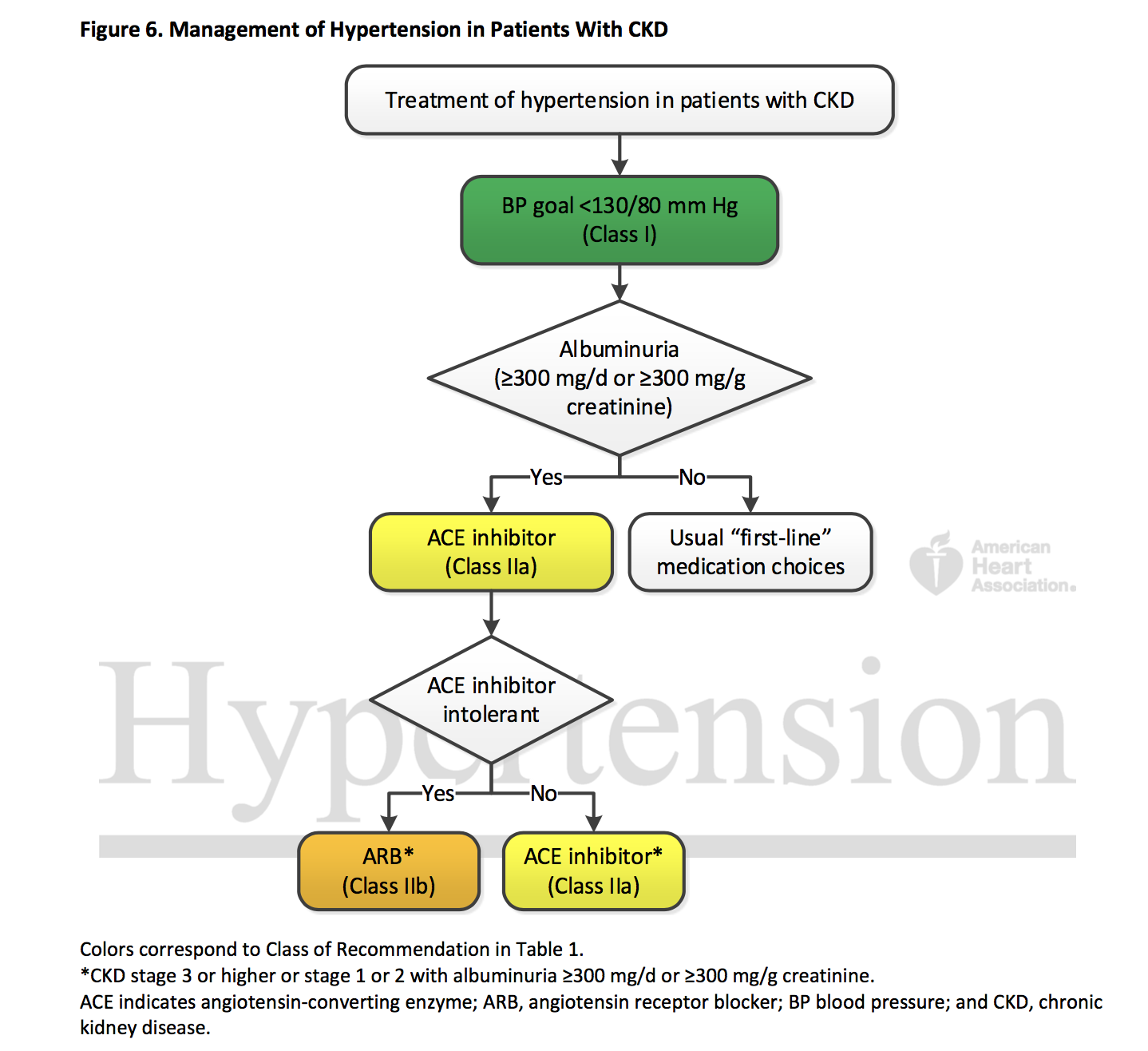

Though this doesn't seem very complicated. there is a simple accompnaying algorithm (figure 6)

Figure 6 from Whelton et al, JACC 2017

Why 130/80 for CKD? SPRINT of course - also check out the SPRINT CKD and SPRINT AKI data for more information that is now available since the original SPRINT data came out.

Two additional points to discuss:

- why 130/80 when SPRINT was < 120? This threshold is actually applied throughout the guideline - there isn't a precise explanation of this in the document itself. From the discussion of these guidelines at the #AHA17, it seems this was a combination of factors including the fact that achieved SBP was ~ 121 in SPRINT, the difference between BP measurement in SPRINT and real life, and lastly that use of this as a performance measure may lead to some targeting well below 120 to ensure all are truly < 120.

- Why ACE-inhibitors if there is albuminuria > 300 mg/day? mainly on the basis of AASK and the Jafar meta-analysis (not discussed: outcome in those trials was progression of CKD - not CV outcomes or mortality).

What about CKD on dialysis? No discussion. If you are interested, here is a nice comprehensive review, and JASN has published a pilot RCT recently, so we may have some good data in time for ACC/AHA 2020.

What about CKD post renal transplantation?

Target remains the same (citation [1] above is SPRINT - though LOE B-NR refers to non-randomized well done observational/registry studies). The CCB choice comes from a Cochrane review (where a decreased graft loss is the only important outcome to show benefit by a whisker: RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.57 to 0.99); there is also a subsequent SR showing lack of benefit of RAS blockade in this population which they don't cite.

Another renal-related guideline? Appropriately, no revascularization for atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis (unlike the SCAI guidelines). Reasonable for fibromuscular dysplasia (as the Canadian guidelines also recently revised).

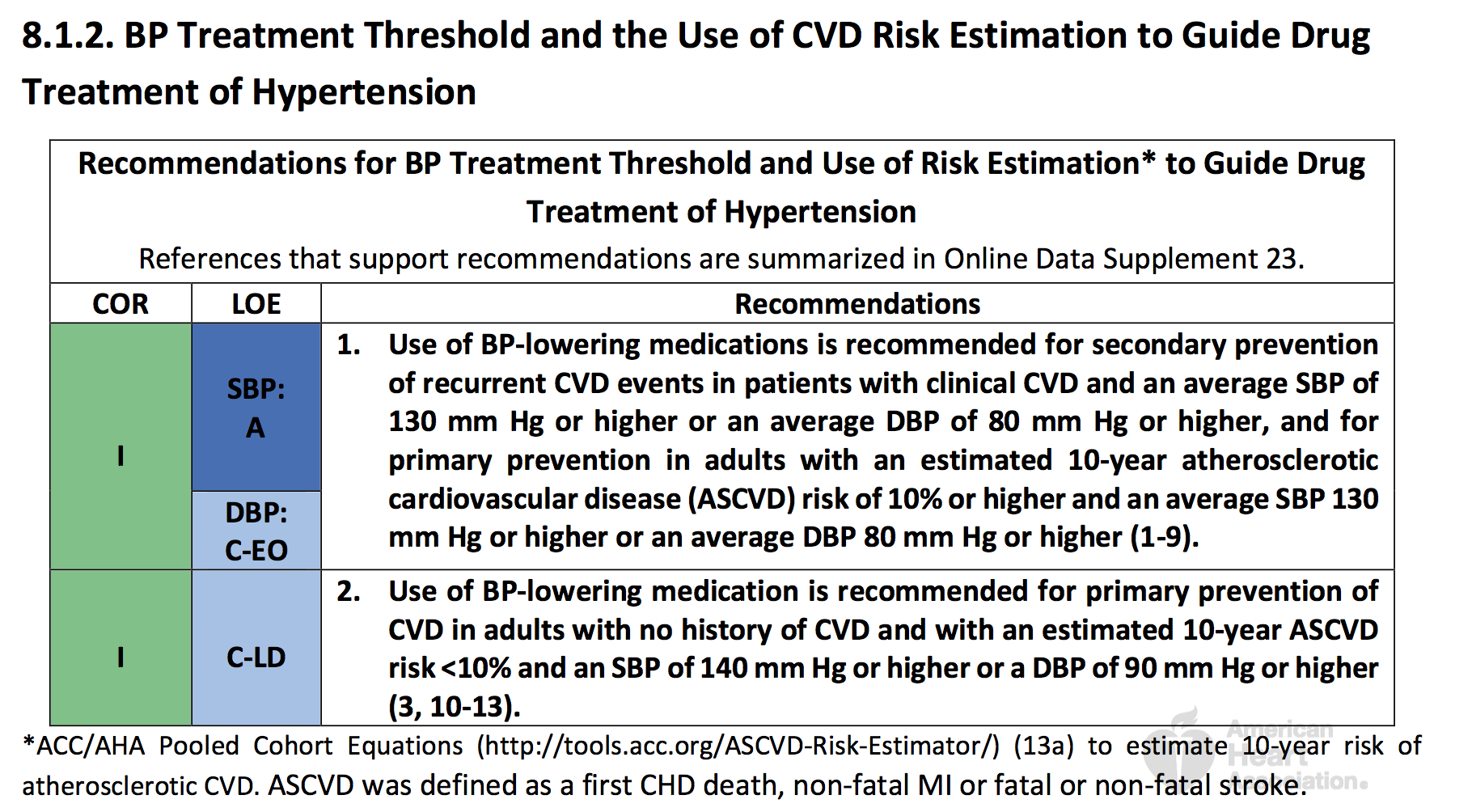

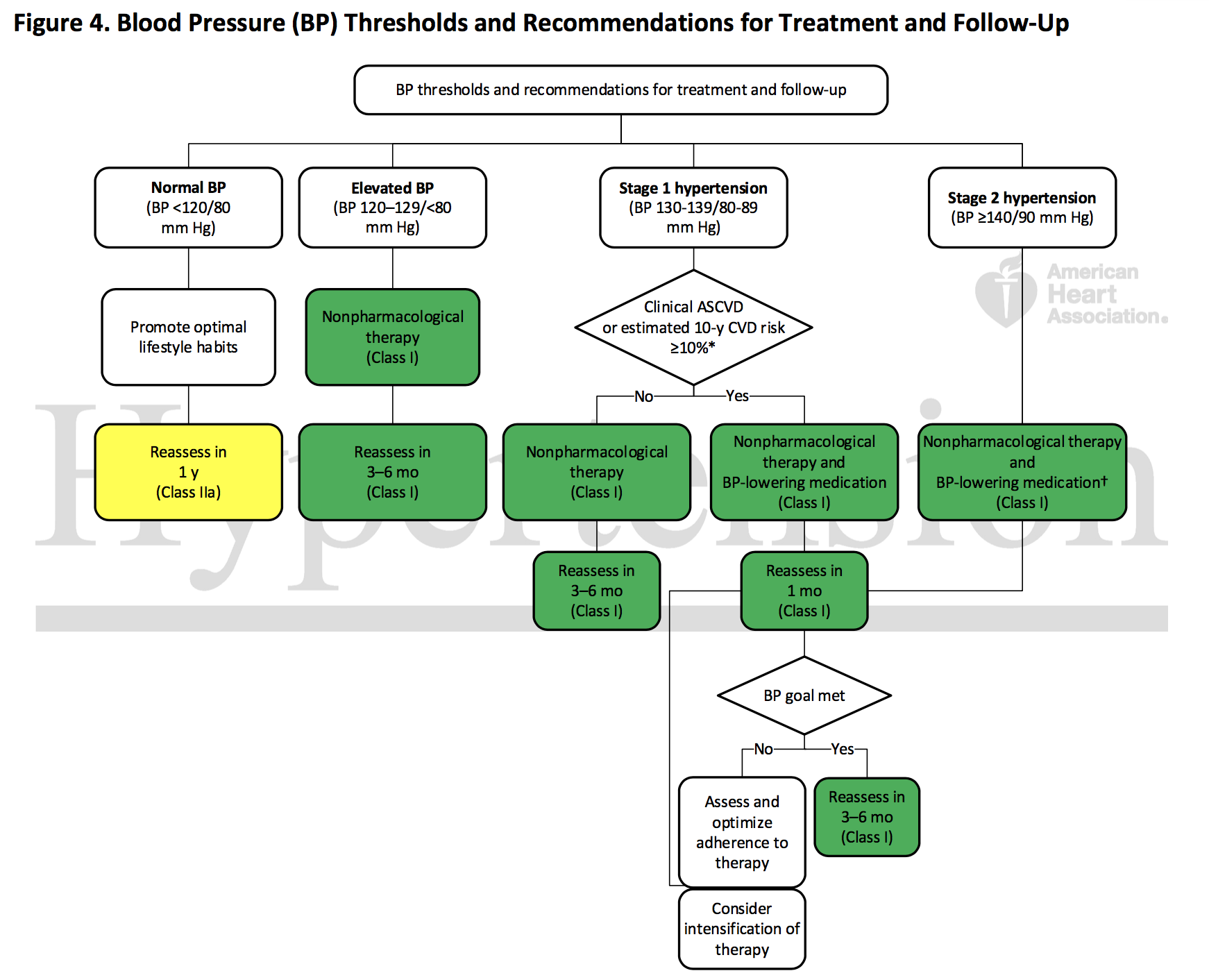

BP target for low risk individuals

Section 8.1.2: BP target < 130/80 of high cardiovascular risk. Also < 130/80 for low cardiovascular risk. Both strength I, with the only difference being level of evidence plummeting from A (based on SPRINT and other studies) to EO = expert opinion for the latter. Is Aaron Carroll right to think this will cause harm? Are our monthly blog reviewers correct in their humorous critique?

The rationale for treating low risk down to 130/80? The expert opinion is based on:

Observational data suggesting the relationship of SBP with risk of CV disease is continuous across levels of SBP and similar across groups that differ in level of absolute risk.

Second, the relative risk reduction with BP lowering is consistent across the range of absolute risk observed in trials.

Finally, modeling studies.

And how should we treat this low risk patients? Great suggestion to start with non-pharmacological therapy first - but re-assess in 3-6 months?

3-6 month follow up for 'elevated BP' ( SBP = 120-129) will be a lot of individuals if you consider there is no mention of CV risk here. The evidence is presented in table 8.1.3 (page 77). Citations 1 and 2 (see below), to support this level of evidence, are the SPRINT and ACCORD methods papers, respectively. The trials, curiously enough, included high CV risk and diabetic patients respectively.

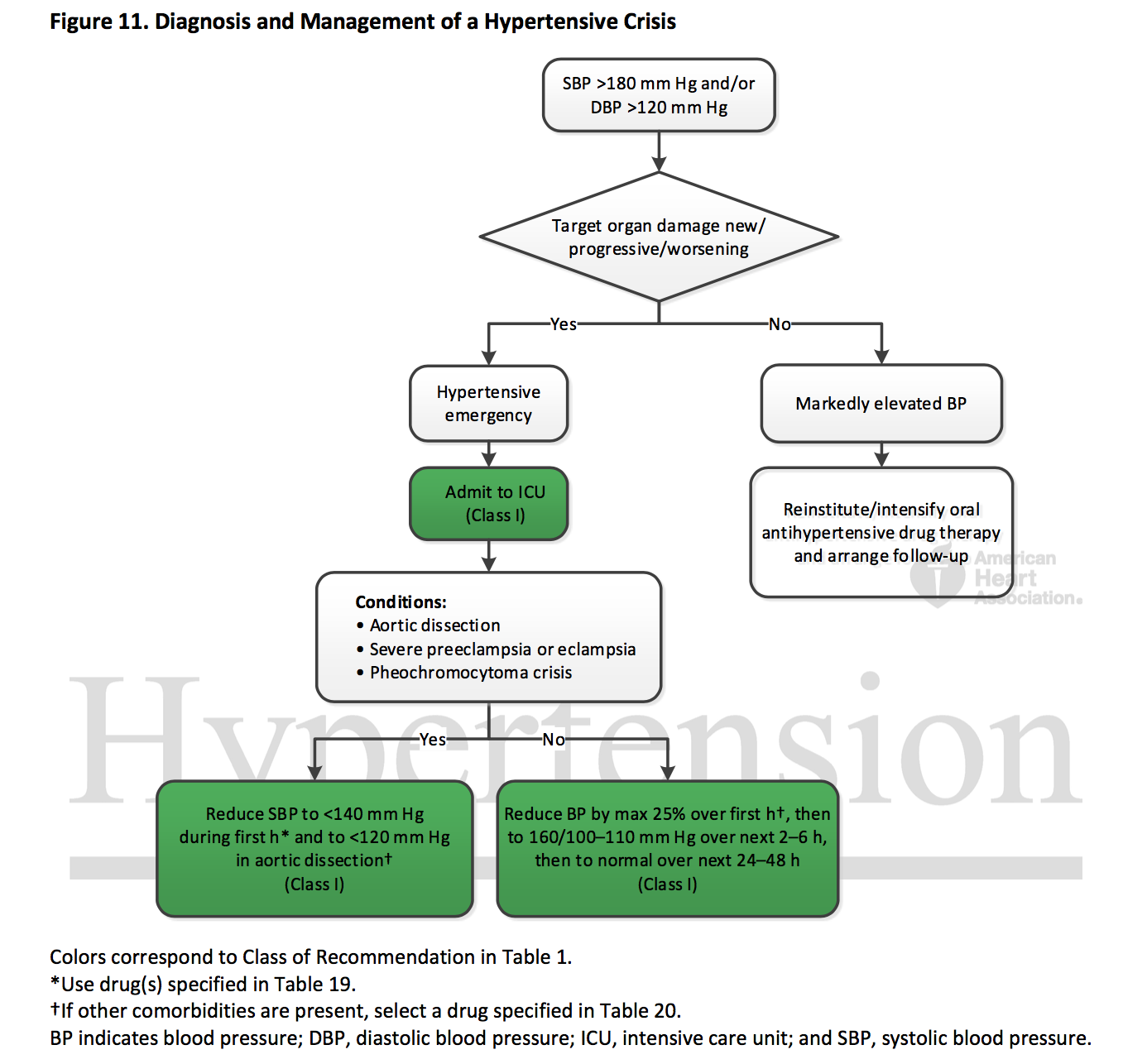

So the level of BP for hypertensive emergency is BP > 180/120 (no 'and/or' qualifiers for systolic > 180 versus diastolic > 120, which are likely quite different here).

Target organ damage from text "include hypertensive encephalopathy, ICH, acute ischemic stroke, acute MI, acute LV failure with pulmonary edema, unstable angina pectoris, dissecting aortic aneurysm, acute renal failure [sic], and eclampsia." Presumably this evaluation should be done immediately, since presence of some of these must be followed by immediate BP lowering. Some of these are clinical diagnoses - but many aren't - so there is understandable concern about further referrals to crowded emergency rooms. Uncited is recent research showing the dysutility of hypertensive urgency (> 180/110) evaluation in the emergency departments. Of interest might be these Dutch guidelines from 2010, which state: "a hypertensive crisis usually develops when BP values exceed 120 to 130 mmHg diastolic and 200 to 220 mmHg systolic" and then "Severe hypertension, defined as a BP between 180/110 mmHg and 220/130 mmHg without symptoms or acute target organ damage, is not considered a hypertensive urgency and is treated as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease"

Tables 19 and 20 do give helpful advice about use of medications in this setting.

Other points to consider

Lest it seem like we are engaging in an extensive critique, there are several extremely salutary aspects to these guidelines.

In high cardiovascular risk, after SPRINT, it was apparent that the JNC 2014 recommendations (< 140 for all, < 150 for age > 65 years) could no longer be considered perfect. This changes that. It can be considered the single most important aspect of this guideline. Though you are allowed to quibble about the use of the ASCVD risk score rather than the Framingham risk score to stratify.

There is no 'elderly' therapeutic nihilism for the non-institutionalized ambulatory elderly, who get a <130/80 target as all others - though the ACP/AAFP disagree with this aspect.

Its not all about pill-popping: lifestyle modification gets a fairly significant section (pages 39 - 42 and 55-56)

Check out pages 149-162 for very useful & practical discussion of adherence, health literacy, team-based interventions and more.

Last, but not the least: what about the patient perspective? Very interestingly, 2 of the 21 authors (Karen Collins and Crystal Spencer) are 'Lay Volunteer/Patient Representative'. Despite this, as two commentators point out (gated link):

"The level of risk that members of the public are willing to accept before initiating treatment might be substantially higher than that of the medical profession, with more than one-third of individuals refusing medication that would reduce their absolute risk by even 5% over 5 years (NNT <20), a much larger gain than typically available from antihypertensive drugs. This refusal might reflect the confusion that many people feel regarding the aetiology of raised blood pressure, which is widely considered to be caused by stress across a variety of international settings."

Remember, we will focus on a few key aspects for the #NephJC chat:

The BP recommendations for chronic kidney disease

Management of hypertensive crises

BP targets for low risk individuals

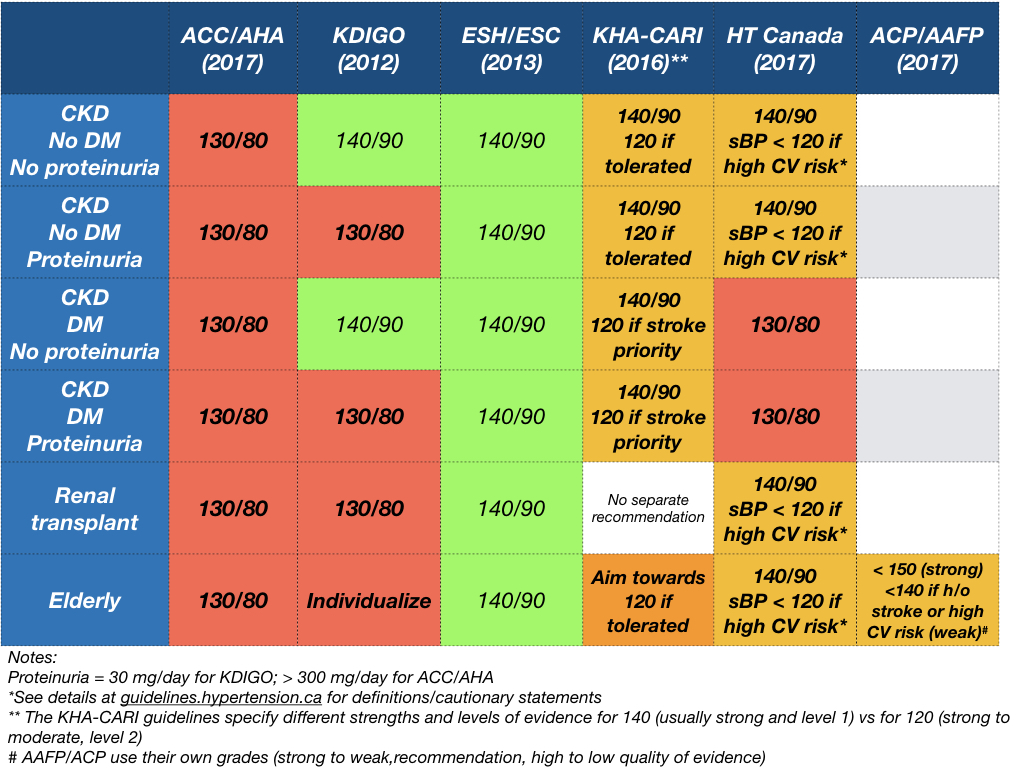

A snapshot of the renal guidelines from different organisations:

References to other guidelines:

Summary by Swapnil Hiremath, nephrologist, Ottawa, Canada