#NephJC Chat

Tuesday, November 14th, 2023, 9 pm EDT

Wednesday, November 15th, 9 pm IST or 2:30 pm GMT

JAMA Intern Med. 2023 Nov 3, doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2023.5802

.

Effect of a Novel Multicomponent Intervention to Improve Patient Access to Kidney Transplant and Living Kidney Donation

The EnAKT LKD Cluster Randomized Clinical Trial

Amit X. Garg, Seychelle Yohanna, Kyla L. Naylor, Susan Q. McKenzie, Istvan Mucsi, Stephanie N. Dixon, Bin Luo, Jessica M. Sontrop, Mary Beaucage; Dmitri Belenko, Candice Coghlan, Rebecca Cooper, Lori Elliott, Leah Getchell, Esti Heale, Vincent Ki, Gihad Nesrallah, Rachel E. Patzer, Justin Presseau, Marian Reich, Darin Treleaven, Carol Wang, Amy D. Waterman, Jeffrey Zaltzman, Peter G. Blake

PMID: 37922156

Introduction

Kidney transplantation was first successfully performed in 1954. Since then, advances in surgical techniques and improved immunosuppression strategies have led to graft survival exceeding 95% at one year. The survival statistics for patients are also evident; each deceased-donor transplant extends the recipient’s life by 8-12 years on average, while living-donor transplants extend the life of a recipient by 12-20 years on average (Poggio ED et al, Am J Transplant 2021). Unfortunately, approximately 14 people with CKD die each day in the US awaiting a kidney transplant, despite an increasing number of transplants performed. In fact, kidney transplant procedures surpassed 25,000 for the first time in the United States in 2022, up more than 10% from just 5 years ago (Lentine KL et al, Am J Transplant, 2023).

Image from UNOS.org

Despite the benefits of organ transplantation, many end-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients are not able to successfully navigate the complex multi-step system required to obtain a kidney transplant. Being waitlisted for a kidney transplant is not a simple checkbox - one needs to be referred, one needs to attend several medical appointments and an array of tests - all the while living your life and undergoing dialysis - and then hope everything checks out fine to be successful in getting on the precious transplant waitlist. So, it’s easy to see why there are many barriers to kidney transplantation, including financial, education, transportation, and health status. Finally, these hurdles are not only present for patients, but also for their families, healthcare professionals, transplant centers, and health systems.

The Enhance Access to Kidney Transplantation and Living Kidney Donation (EnAKT LKD) took a deep dive into trying to overcome the barriers to transplantation by implementing a novel multi-component intervention in an effort to improve rates of successful kidney transplantations.

The Study

Methods

Design: open-label, pragmatic, cluster randomized control trial (RCT) of 26 CKD programs in Ontario, Canada.

Study dates: November 1, 2017 - December 31, 2021

Population: This was a cluster RCT, thus each dialysis center was a unit of the cluster. All renal programs in Ontario (a Canadian province) were units for these cluster RCT.

Inclusion criteria: Age 18-75 with potential for being transplant-eligible (no contraindications). Patients entered the trial with eGFR <15 ml/min OR ≥ 25% 2-year predicted risk of kidney failure via the kidney failure risk equation (KFRE).

Table 1. Patient eligibility criteria for inclusion in the EnAKT LKD trial, from Dixon SN et al, Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2022

Randomization: 26 CKD programs were divided into 2 groups and randomized to receive quality improvement intervention vs usual care using computer-generated random allocation.

Intervention: Multicomponent intervention designed by an 18-member panel having 4 main components: quality improvement/administration, education, patient support, and data/ accountability as described below.

1. Quality improvement/administration

At each of the 26 CKD programs in Ontario, local quality improvement teams were developed to understand and improve local performance. The team included a team lead, an executive sponsor (usually from the hospital administration), local personnel with quality improvement experience, and at least 2 patients, one of whom is involved in the Transplant Ambassadors Program (TAP). Teams were trained to use a Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) model for local improvement projects. These teams met monthly via teleconference or in-person to share. progress and discuss strategies for overcoming barriers to transplant. Provincial support was also given to 13 out of 26 CKD teams, which included $10,000 per year for support funds.

2. Education

This intervention aimed to increase knowledge regarding the transplantation process, specifically living kidney transplants, for healthcare providers, patients, and their families. The EnAKT LKD education was led by 3 transplant education experts and each CKD center’s quality improvement team. Healthcare providers were asked to review the transplant education process (gathered from Up-to-Date) at www.ontariorenalnetwork.ca with specific modules on when to refer to transplant centers and online risk calculators for dialysis vs transplantation. Patients and families received educational materials on making informed decisions about kidney transplant and living donation, finding living donors in Ontario and abroad, and raising awareness about living donation. Moreover, CKD programs were supported by a personalized education program called Explore Transplant Ontario (https://etontario.org/). Explore Transplant Ontario has guided discussions based on the patient's CKD stage to assess their readiness for considering transplant. An RCT found that dialysis patients who received Explore Transplant program education vs standard education had greater transplant knowledge, were more likely to be evaluated for transplant, and had more living donor candidates (Waterman AD et al, Prog Transplant, 2018).

3. Patient support

The Transplant Ambassador Program is led by and was developed to support patients and their families in their transplant journey, especially concerning living kidney transplants. The ambassadors have experience of living donation or transplantation in general and volunteer their time in dialysis centers and clinics to connect with patients and their families and help them make decisions. Ambassadors receive training in mentorship, communication, and patient education without medical advice. Due to their volunteer efforts, they often spend more time with patients than healthcare workers.

4. Data/ accountability program-level performance monitoring

This was done using existing administrative health data and facilitated data sharing among CKD programs and transplant centers in this form of intervention. Quarterly reports summarize various transplant-related metrics as well as process measures i.e., the number of patients who completed the Explore Transplant Ontario program.

Here is a summary of the multicomponent intervention:

Outcomes

The primary outcome was rate of steps completed toward receiving a kidney transplant. There were 4 steps that were evaluated:

referral made to transplant center for evaluation

potential living donor contact a transplant center for evaluation

patient added to deceased donor list

received a transplant from a living or deceased donor.

Secondary outcomes were also measures that focused on living donor evaluation or living donor transplants performed, how many living donors were able to contact transplant centers for evaluation, whether living donors were easily referred for evaluation, and if pre-emptively living donors were already identified for transplant.

Analysis: The study aimed for at least 80% power to detect a significant between-group difference of 12 steps per 100 patient-years, considering the assumed rate of 23 steps per 100 patient-years in the usual care group, with a 2-sided fold α of 0.05.

Intention to treat analysis was completed between October 2022 and March 2023, stopping patient observation upon reaching the trial's end, death, transplant, renal function recovery, or transplant eligibility.

The authors initially planned for a cluster-level analysis but changed to a patient-level analysis with a multistate statistical model for the primary outcome. This change was motivated because patient-level analysis would provide more statistical precision and better accommodate variable cluster sizes. The primary outcome, including 4 steps toward kidney transplant, argued for a multistep statistical model.

Prespecified analyses examined the intervention effects in unadjusted and adjusted models. Post-hoc analyses explored intervention effects in subgroups and assessed potential contamination bias.

Funding sources: Funding was received from Can-SOLVE CKD (Canadians Seeking Solutions and Innovations to Overcome Chronic Kidney Disease), the Provincial Access to Kidney Transplantation and Living Donation Priority Panel and the Ontario Renal Network–Trillium Gift of Life Partnership. This study was also supported by ICES, which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health (MOH) and the Ministry of Long-Term Care (MLTC).

Results

There were 20,375 patients with advanced CKD who were potentially transplant-eligible. A total of 9,780 patients from 13 CKD programs in the intervention group and 10,595 patients from 13 CKD programs in the usual-care group entered the trial.

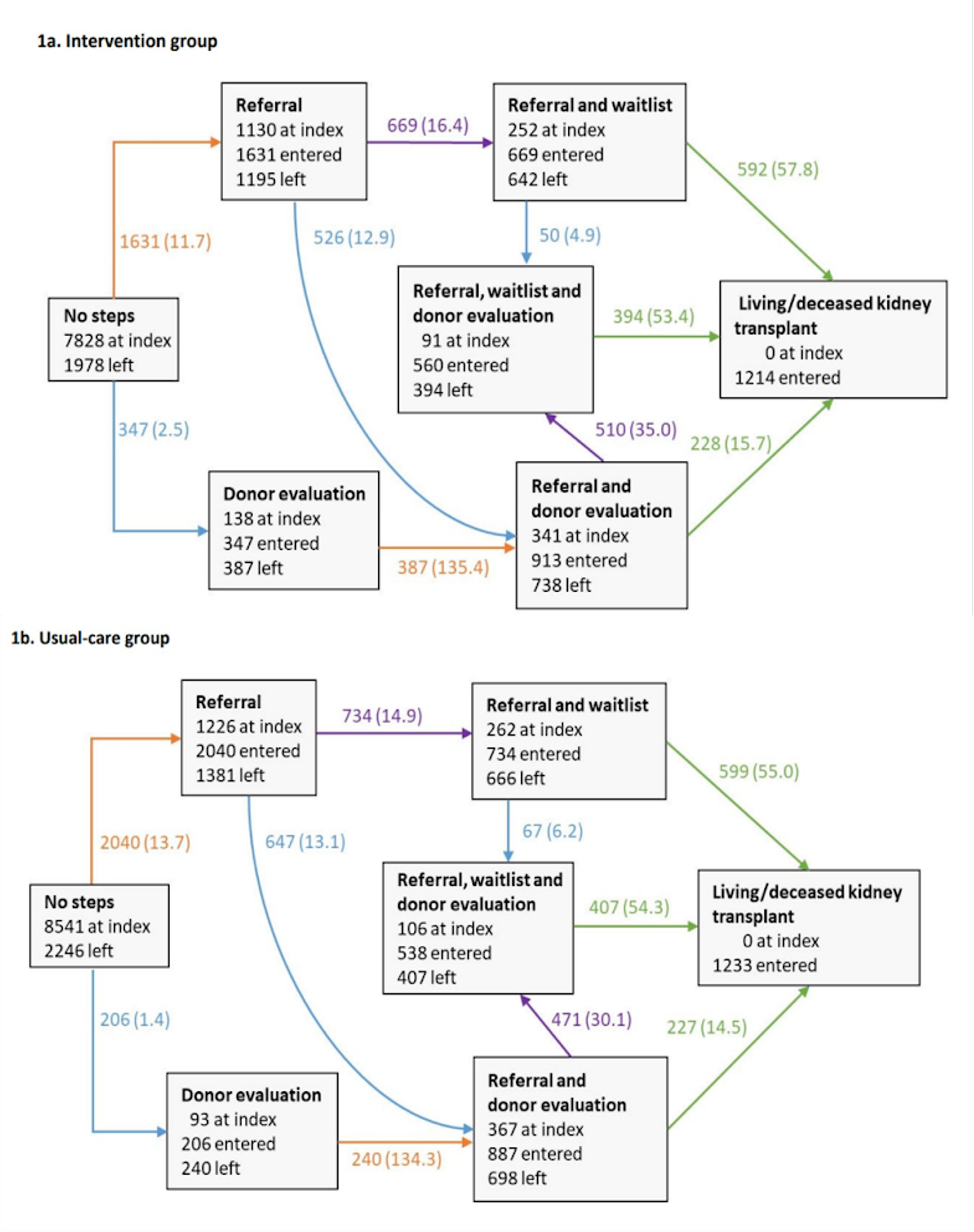

Figure 1. Participant flow of the EnAKT LKD trial, JAMA Intern Med 2023.

The median (IQR) age was 61 (51-69) years, 38% were women, and 57% had diabetes. When they entered the trial, 51% were approaching the need for dialysis, and the remaining 49% were receiving maintenance dialysis. Of those approaching the need for dialysis, the median (IQR) eGFR was 16 (13-20) mL/min per 1.73 m2, the median (IQR) albumin-to-creatinine ratio was 162 (69-314) mg/mmol, and the 2-year predicted risk of kidney failure was 45% (32%-67%). Of these patients, 48% started maintenance dialysis during the trial.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics from EnAKT LKD trial, JAMA Intern Med 2023.

Intervention Uptake

Each local transplant team established objectives and activities and assessed the performance of the transplant program. Monthly meetings were scheduled, and 1,740 patients completed the Explore Transplant Ontario program. Transplant ambassadors (previous kidney transplant recipients) recorded 5,471 interactions with patients with advanced CKD and 719 with potential living kidney donors.

The start of the COVID-19 pandemic affected the execution of the intervention for at least a year. Transplant activity ceased temporarily, and follow-up visits were transitioned from in-person to virtual meetings.

Primary Outcomes

Despite evidence of intervention uptake, the step completion rate did not significantly differ between the intervention vs usual-care groups: 5334 vs 5638 steps; 24.8 vs 24.1 steps per 100 patient-years; adjusted hazard ratio, 1.00 (95% CI, 0.87-1.15) (table 2).

Table 2. Effect of the Quality Improvement Intervention on the Rate of Steps Completed Toward Receiving a Kidney Transplant of the EnAKT LKD trial, JAMA Intern Med 2023.

In follow-up, 131 patients (1.3%) in the intervention group completed all 4 steps, and 572 (5.8%), 1493 (15.3%), and 3138 (32.1%) completed 3 or more, 2 or more, and 1 or more steps, respectively. Corresponding numbers in the usual-care group were 129 (1.2%), 589 (5.6%), 1538 (14.5%), and 3382 (31.9%), respectively.

Also, a multistate model for the intervention and usual-care groups was created. Arrows indicate transitions from one state to another. The different colored arrows indicate the steps completed in the transition:

• An orange arrow indicates a patient was referred to a transplant center for evaluation.

• A blue arrow indicates a patient had a potential living kidney donor contact a transplant center for evaluation.

• A purple arrow indicates a patient was added to the deceased donor waitlist.

• A green arrow indicates a patient received a kidney transplant from a living or deceased donor.

eFigure 1a and 1b (Supplement 3). Multistate model for the intervention and usual‐care groups from the EnAKT LKD trial, JAMA Intern Med 2023.

Secondary Outcomes

There were no differences between groups focused on starting a living donor evaluation or restricted to living donor transplant, each 95% CI of the hazard ratio contained a value of 1.0 (Table 2).

Discussion

The ENAKT trial made a valiant effort to incorporate a multicomponent novel intervention to increase the rate of steps needed toward successful kidney transplantation. While the results did not find any increase in step completion versus usual care, the size, scope, and systematic approach implemented in this trial to dismantle barriers to transplant was quite encouraging. 6 specialized kidney clinics (for patients approaching the need for dialysis), 26 home dialysis programs, 97 hemodialysis units, more than 3400 nurses, and 230 nephrologists were part of this titanic effort. Pessimists would say the results were negative, and they indeed were when it comes to implacable hazard ratios. However, on a positive note, this trial showed that administrators, healthcare staff, patients, and nephrologists were able to coordinate and implement a multicomponent intervention on a large scale, which in itself is quite a feat! More specifically, data collection and sharing allowed for presenting detailed performance reports to CKD programs for the first time. While implementing interventions on this scale was already a monumental task, the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic 2.4 years into the 4.2-year trial significantly affected intervention delivery for at least 1 year. Moreover, not only did transplant surgeries halt, but quality improvement teams met less often, transplant ambassadors moved to virtual meetings, and healthcare staff retired or redeployed.

Outside of the minor shortcomings listed above, other limitations present for this study included: data may not be generalizable to other health systems and geographical areas; inequities in kidney transplantation were not addressed. Another recently published trial did try specifically to address inequities (Patzer et al, CJASN 2023). This was also a pragmatic, multilevel, effectiveness-implementation trial including 655 US dialysis facilities with low wait listing, randomized to receive either the ASCENT intervention (a performance feedback report, a webinar, and staff and patient educational videos) or an educational brochure. Similar to ENAKT-LD, among the 56,332 prevalent patients in ASCENT, the results were disappointing. The 1-year wait listing decreased for patients in control facilities and remained the same for patients in intervention facilities. However, the proportion of prevalent black patients waitlisted in the ASCENT interventions increased a tiny bit from baseline to 1 year (2.52 to 2.78%). These trials demonstrate that many of these plausible educational and behavioral change interventions still cannot overcome some of the structural barriers/ elements in the transplant journey.

Before we move to the cerebral conclusion, we might still ask ourselves if this was useful beyond the negative results. It depends on which side we choose. Keep in mind that some things can be narrated only by the characters of the transplant stories, by patients, brave donors, and some nephrologists and nurses who witness their stories. Or maybe we can, at least once, find value in the narration and the ray of hope that comes with it. Less metaphorically, Explore Transplant Ontario and Transplant Program Ambassador are reliable resources and a crossroads where many questions can find their answers.

Conclusions

Regardless, the ENAKT trial is a valiant effort to study the barriers to transplantation while enacting a multicomponent novel intervention to the multiple steps required for successful transplantation. These interventions clearly did not work; it is time to stop doing them and test other interventions now. This is why we do RCTs. Negative trials should be practice-changing; we cannot just ignore the results and keep on doing feel-good interventions that are complicated, expensive, and ineffective.

Summary by