#NephJC Chat

Tuesday May 9th 2023 9 pm EST

Wednesday May 10th 9 pm IST

Ann Rheum Dis 2023 Mar 23;ard-2022-223559. doi: 10.1136/ard-2022-223559. Online ahead of print.

Rituximab versus azathioprine for maintenance of remission for patients with ANCA-associated vasculitis and relapsing disease: an international randomised controlled trial

Rona M Smith, Rachel B Jones, Ulrich Specks, Simon Bond, Marianna Nodale, Reem Al-Jayyousi, Jacqueline Andrews, Annette Bruchfeld, Brian Camilleri, Simon Carette, Chee Kay Cheung, Vimal Derebail, Tim Doulton, Alastair Ferraro, Lindsy Forbess, Shouichi Fujimoto, Shunsuke Furuta, Ora Gewurz-Singer, Lorraine Harper, Toshiko Ito-Ihara, Nader Khalidi, Rainer Klocke, Curry Koening, Yoshinori Komagata, Carol Langford, Peter Lanyon, Raashid Luqmani, Carol McAlear, Larry W Moreland, Kim Mynard, Patrick Nachman, Christian Pagnoux, Chen Au Peh, Charles Pusey, Dwarakanathan Ranganathan, Rennie L Rhee, Robert Spiera, Antoine G Sreih, Vladamir Tesar, Giles Walters, Caroline Wroe, David Jayne, Peter A Merkel; RITAZAREM co-investigators

PMID: 36958796

Introduction

In the world of glomerulonephritis, cures are unfortunately rare. The best we can usually hope for is remission followed by disease relapse suppression by various drug regimens. As author Tom Robbins says: “There’s birth, there’s death, and in between there’s maintenance.” This latest study up for discussion evaluates if rituximab is superior to azathioprine for maintenance of remission in patients with relapsed ANCA-associated vasculitis (AAV). Are you thinking you could be having a déjà vu moment? Some of you might recall the NephJC team discussing the MAINRITSAN 1 trial in 2014, comparing rituximab to azathioprine for maintenance treatment of AAV. While the plotline for today’s discussion sounds familiar to the 2014 debate, a rematch was needed to resolve some of the unanswered questions from MAINRITSAN. The current study, RITAZAREM, focused exclusively on enrolling patients with AAV once they had experienced a relapse.

Various long term trials have demonstrated patients with AAV commonly deal with relapse. This relapse rate can be as high as 80% over a span of 5 years (Tables 1 and 2). Such relapse episodes are major contributors to increased morbidity and mortality. While therapeutic agents like steroids, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab have been immensely successful in inducing clinical remission, preventing relapses remains an area of interest. This is especially true for patients with relapsing disease.

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) and microscopic polyangiitis (MPA) are two major subtypes of ANCA-associated vasculitis. B cells play an important role in AAV pathogenesis, not only via autoantibody generation, but also by acting as antigen presenting cells and by secreting inflammatory cytokines. Rituximab is a monoclonal antibody directed against the CD20 antigen found on the surface of B cells. Rituximab-based regimens remain the mainstay of induction therapy for AAV, and have been shown to be non-inferior to conventional treatments like cyclophosphamide. However, the RAVE trial revealed that only 39% of patients maintained remission at 18 months following a single course of rituximab, indicating the need for improved maintenance regimens. Furthermore, the MAINRITSAN 1 trial demonstrated rituximab as being superior to azathioprine at maintaining remission in AAV following remission with cyclophosphamide, primarily in newly diagnosed cases. However, relapses still occurred once maintenance treatment was discontinued, and relapse rates are known to be higher in patients with a history of prior relapse.

Figure: B cell playing a central role in mediating auto-immune disease including ANCA antibody production.

While prolonged use of rituximab could aid in preventing AAV recurrence, it is known to be associated with increased risk of infection due to hypogammaglobulinemia. The optimum strategy to maintain remission, especially after inducing remission with rituximab, remains unclear. Some of the unanswered questions from MAINRITSAN trial include:

What is the efficacy of rituximab in preventing relapses in the subgroup with a history of relapsing disease?

The MAINRITSAN trial was underpowered for this subgroup. 23 of 115 participants had relapsing disease.

What is the optimal remission maintenance strategy (dose/timing) following rituximab induction therapy?

The Study

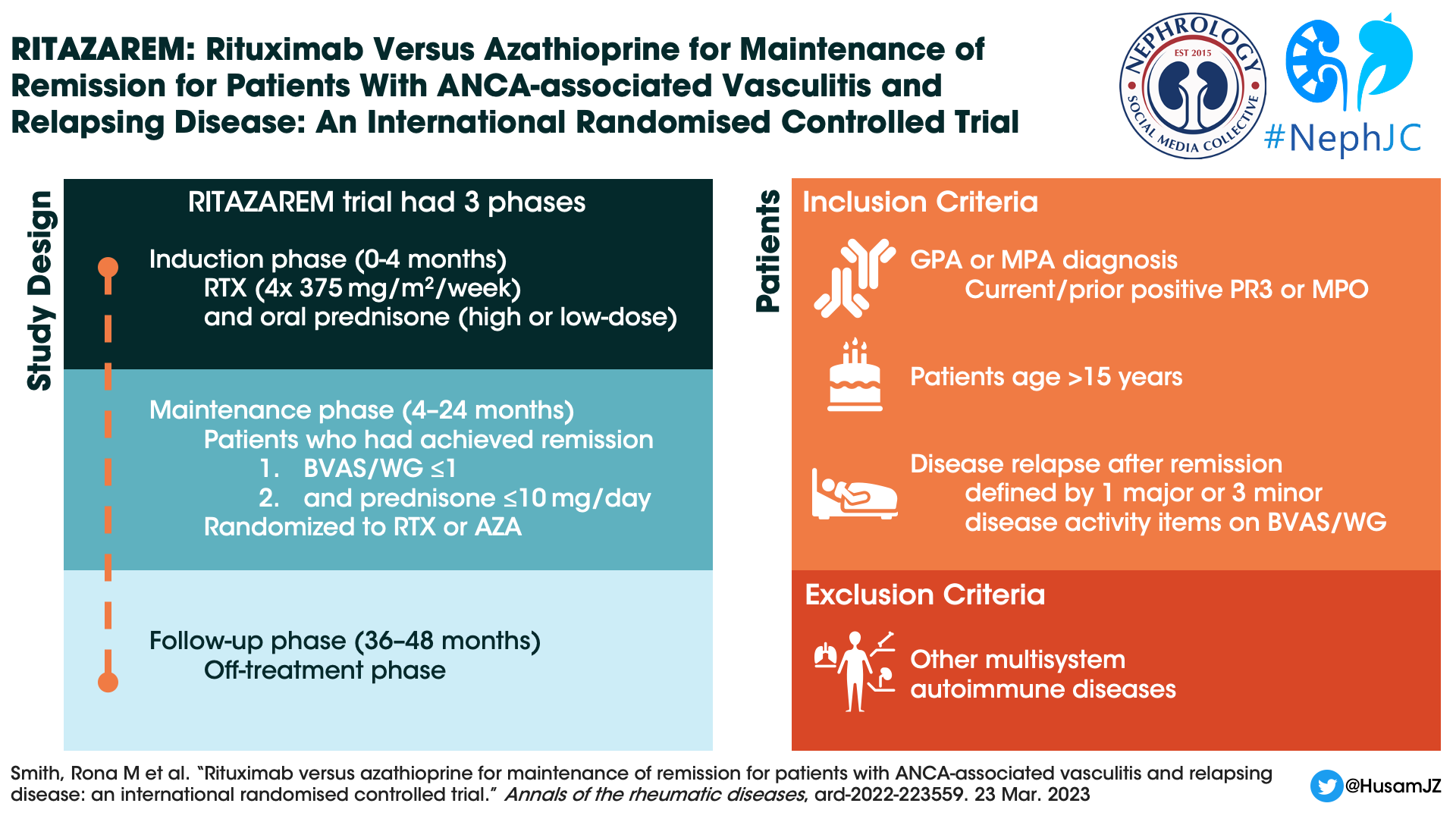

RITAZAREM was an international, randomized controlled, open-label, superiority trial done in three phases:

Induction Phase (enrollment until month 4) - Induction therapy was a combination of rituximab (four doses of 375 mg/m2 per week) with corticosteroids.

Maintenance Phase (months 4 to 24) - This phase identified successful remission defined as ≤1 on Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score for Wegener’s granulomatosis (BVAS/WG) and prednisone dose ≤10 mg/day. Patients who achieved remission by month 4 were then randomised to receive either rituximab or azathioprine. Patients not in remission by month 4 were excluded.

Follow-up Phase (months 36 to 48) - Once the maintenance phase was completed, patients were followed off treatment for a minimum of 12 and maximum of 24 months, to monitor for further relapse episodes.

Study Population

Patients who were > 15 years old and had a diagnosis of GPA or MPA according to the 2012 Chapel Hill Consensus Conference definition. Patients were recruited from seven countries amongst 29 centres between April 2013 and November 2016. Other notable exclusion criteria included:

Receipt of any biological B cell depleting agents within 6 months of the study

Receiving IVIG, anti-TNF treatment or plasma exchange within 3 months of the study

Patients with other auto-immune multisystem disease such as eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (eGPA), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), or anti-glomerular basement membrane (GBM) disease

History of malignancy within 5 years prior to study

Study Design

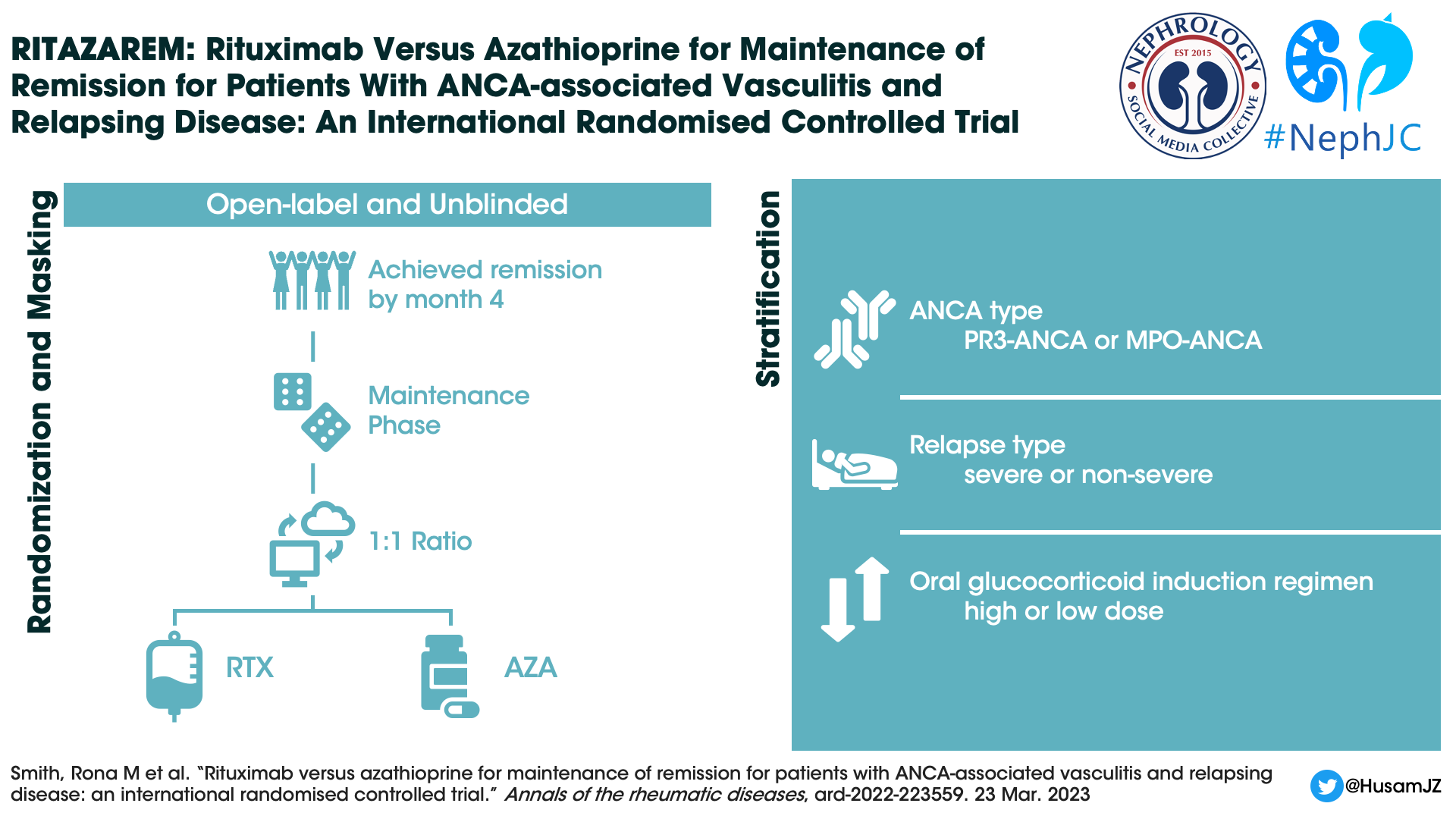

This was an open label unblinded study, where participants were randomized (1:1) into each arm using a web-based system. Patients were stratified based upon:

ANCA type - PR3-ANCA vs MPO-ANCA.

Relapse type (severe vs non-severe)

Severe relapse: any item of major disease activity on BVAS/WG score (for example any neurological involvement, almost all renal involvement, alveolar haemorrhage, mesenteric ischaemia, sensorineural deafness, scleritis or gangrene)

Non-severe relapse: any increase in disease activity not meeting the severe criteria.

Intensity of oral glucocorticoid regimen:

High dose: initial dose 1.0 mg/kg/day

Low dose: initial dose 0.5 mg/kg/day

Interventions

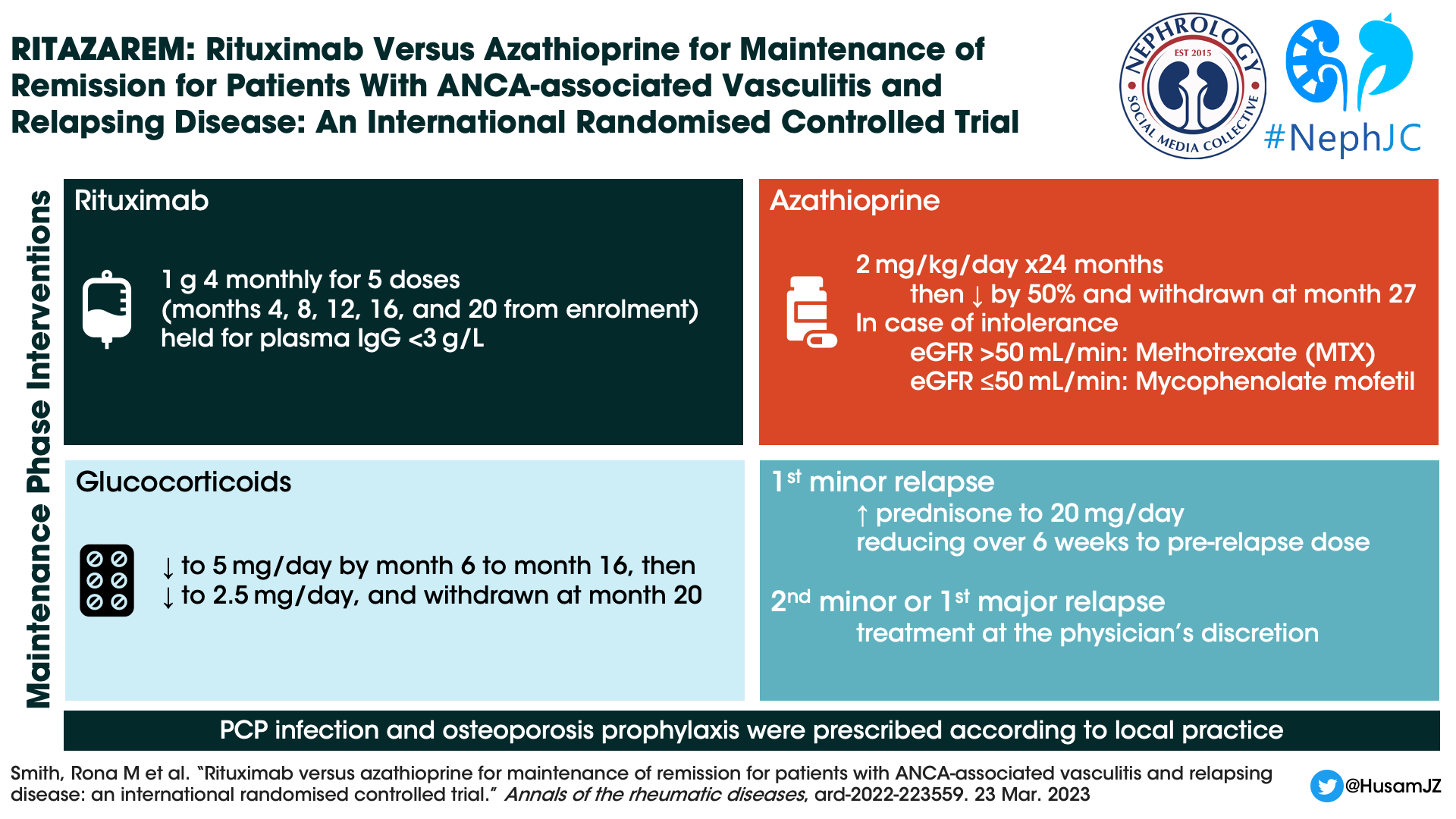

Rituximab Arm: After completing induction therapy, patients received 1000 mg rituximab IV every 4 months for a total of five doses (months 4, 8, 12, 16, 20).

Control Arm: Identical induction phase, followed by maintenance phase with orally administered azathioprine. The dosing was 2 mg/kg/day for the first 24 months, then reduced by 50% and stopped by month 27. Patients who were intolerant to azathioprine, would receive methotrexate (max dose of 25mg/week) if the eGFR was >50mL/min or mycophenolate mofetil 2g/day, if the eGFR was ≤50mL/min.

Concomitant Therapy with Glucocorticoids: (applicable to both study arms)

Induction phase: Patients were permitted to receive a maximum cumulative dose of 3000 mg IV methylprednisolone in the 2 weeks prior or 1 week after enrollment. Similarly, they could get oral treatment in the form of prednisone, either high dose (initial dose 1 mg/kg/day) or low dose (initial dose 0.5 mg/kg/day) based on physician discretion.

Maintenance phase: While oral prednisone up to 10 mg/day was a requirement at time of randomization at 4 months, this dose was tapered down to 5 mg/day by month 6 and continued at this dose until month 16. Afterwards it was reduced to 2.5 mg/day and completely stopped by month 20.

Treatment of relapse: While time to relapse was the primary endpoint, patients experiencing their first minor relapse before month 24 would remain on their randomized treatment, and were treated with oral corticosteroids (up to 20 mg/day of prednisone) for a week and then tapered.

Figure: Treatment schedules taken from slideshow at Gold Plenary session ASN 2019 delivered by Dr Rona Smith.

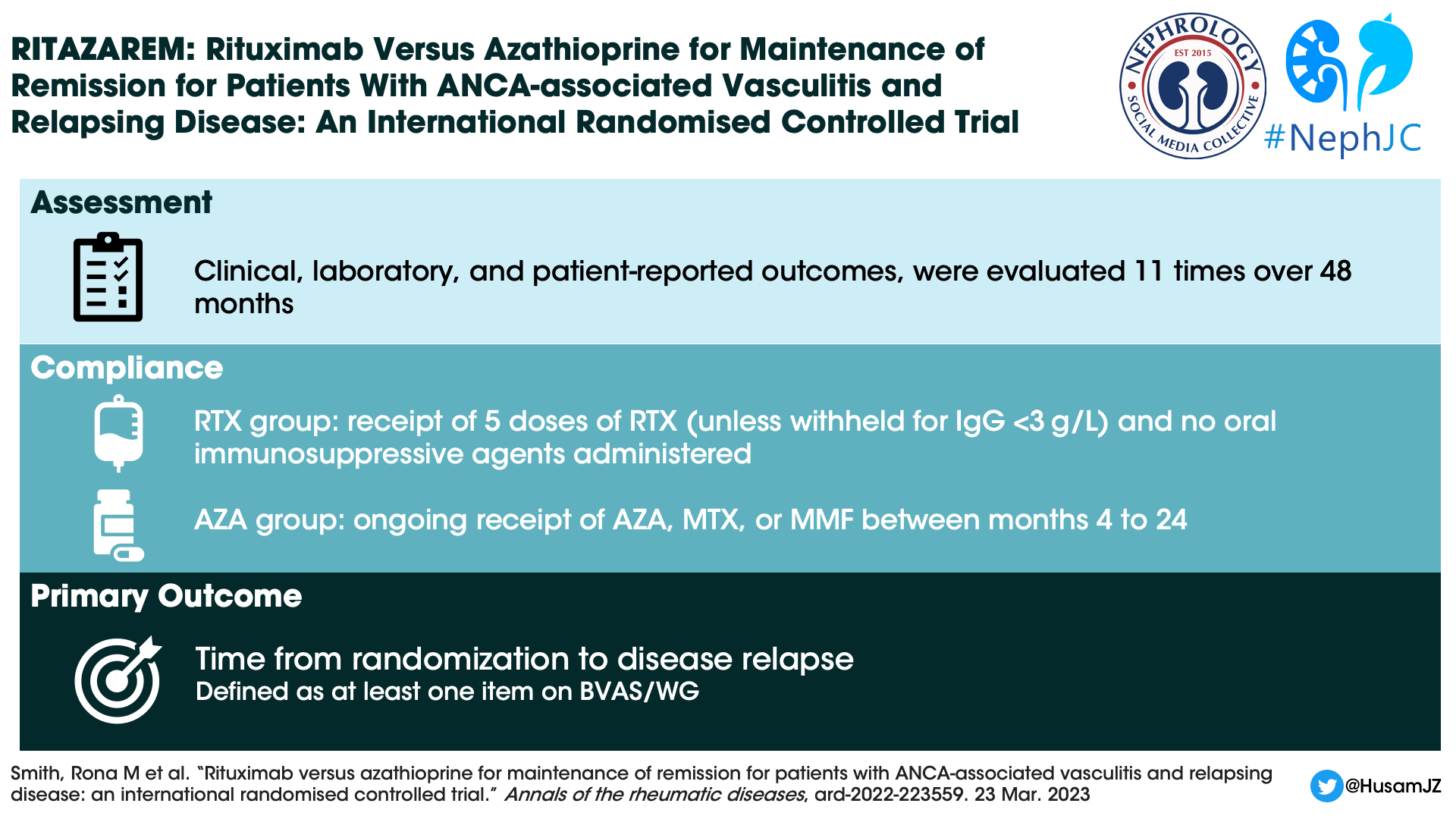

Outcome Measures

Primary Outcome: Time to disease relapse (either minor or major based on BVAS/WG) reported by month 24. Relapses were reviewed by a blinded adjudication committee.

Secondary Outcomes:

Time to a major or second minor relapse.

Proportion of patients who maintained remission at 24 and 48 months.

Health-related quality of life, as measured using a 36-item short form health survey.

Severe adverse event rates and infections that required treatment with antibiotics.

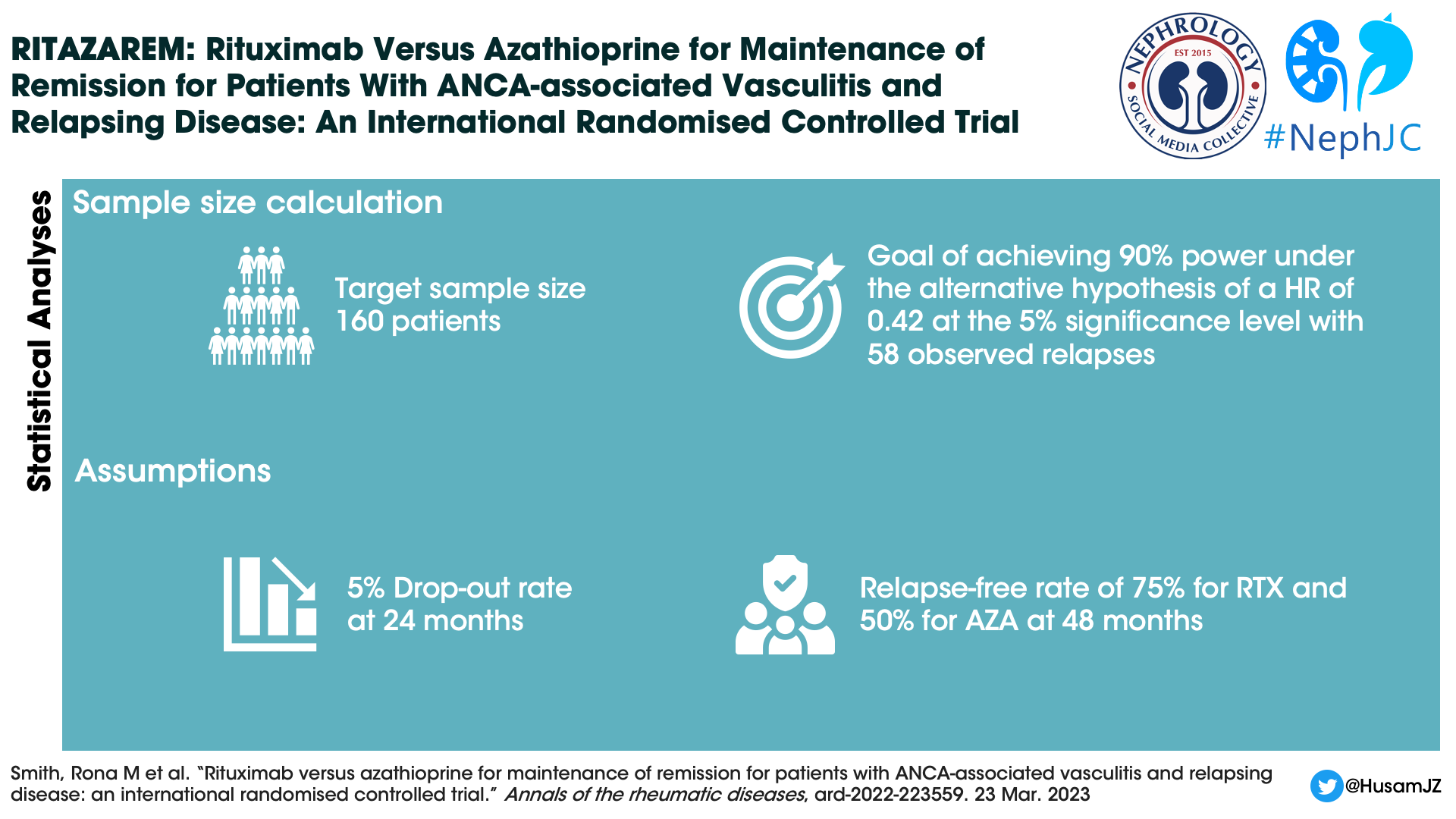

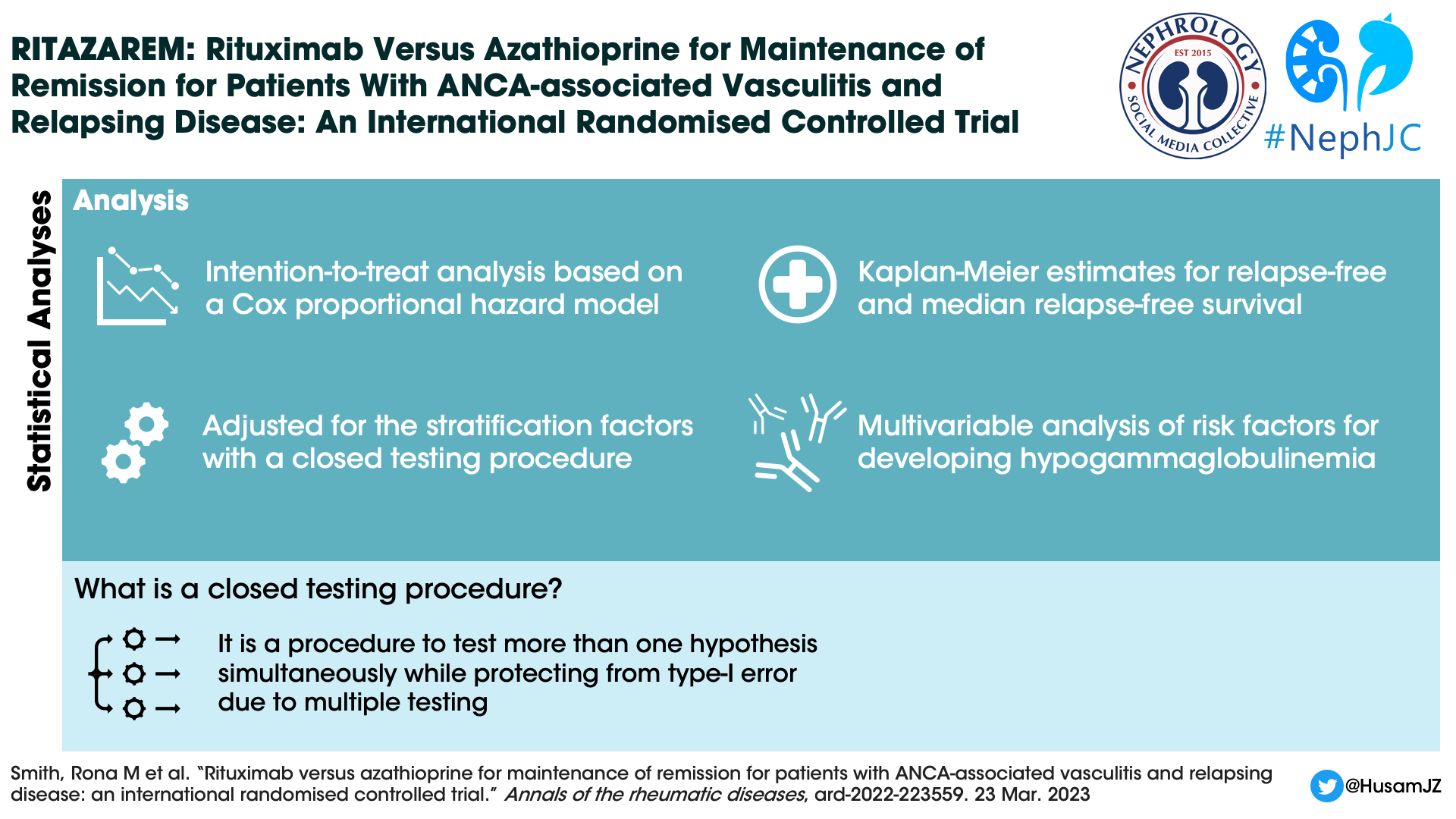

Statistical analysis

Enrolment of patients continued until 160 patients were reached. The sample size was calculated based on the need to achieve a hazard ratio of 0.42, and a power of 90%.

Funding

RITAZAREM was funded by grants from Arthritis Research UK and Roche/Genentech. The primary sponsor was Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust UK.

Results

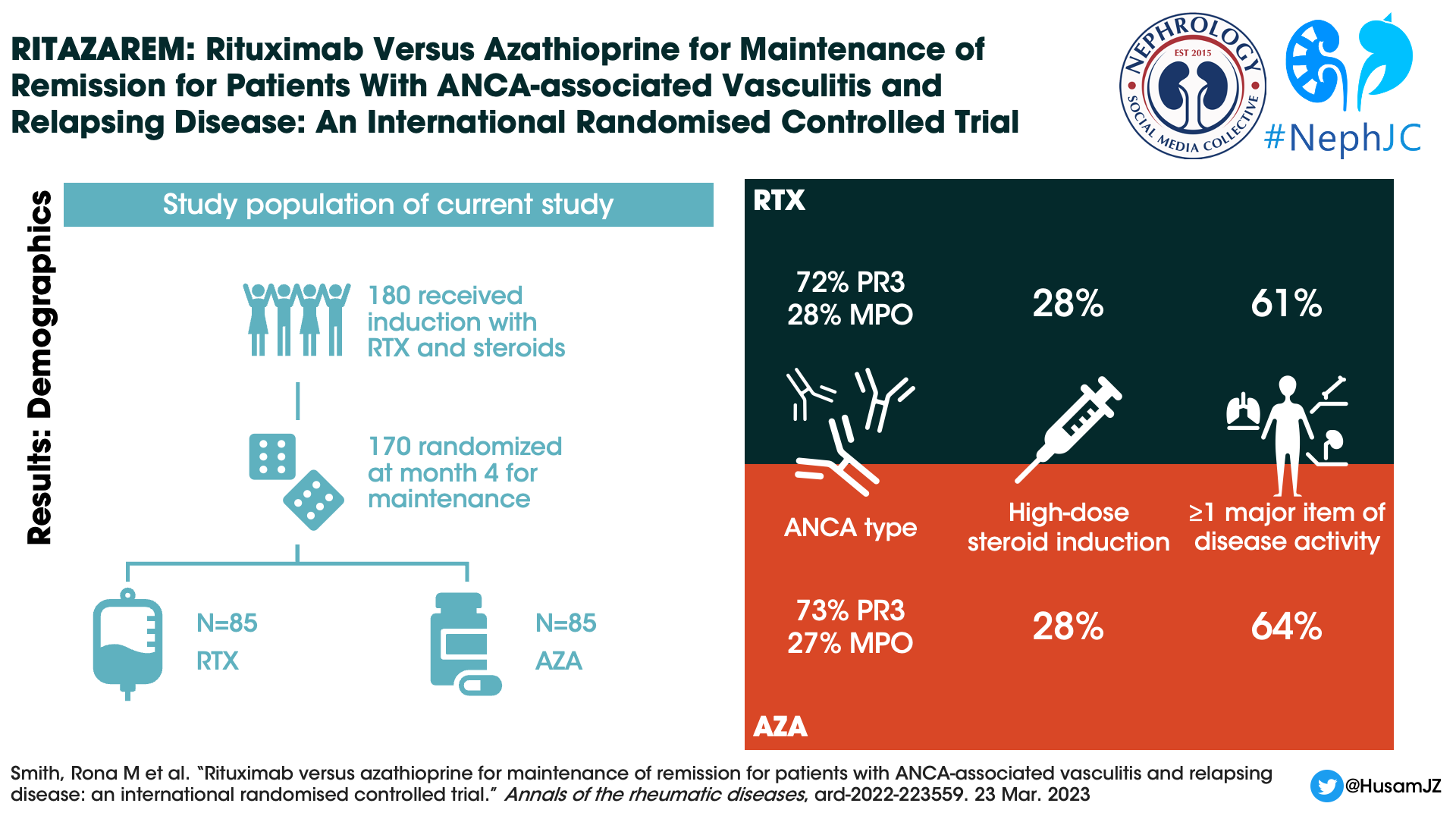

There were 188 patients were enrolled and 187 received rituximab and glucocorticoid induction. At four months only 6 were not eligible for randomization due to not being in remission, leaving 170 patients that underwent randomization (85 patients placed in each study arm).

Figure 1. CONSORT diagram, Smith et al, Ann Rheum Dis 2023

Median age of the patients was 58 years, 91% were white, and 49% were male. Seventy-two percent of enrolled patients were PR3-ANCA positive, and 62 percent of patients had at least one major disease activity item. The high-dose glucocorticoid regimen was received by 28% of patients. Not included in table 1, but presented in the induction paper (Smith et al, ARD, 2020), at the time of relapse ⅓ of study patients were already on oral immunosuppression including 19% of the initial 188 patients were on azathioprine.

Table 1, Baseline demographics of patients. From Smith et al, Ann Rheum Dis 2023

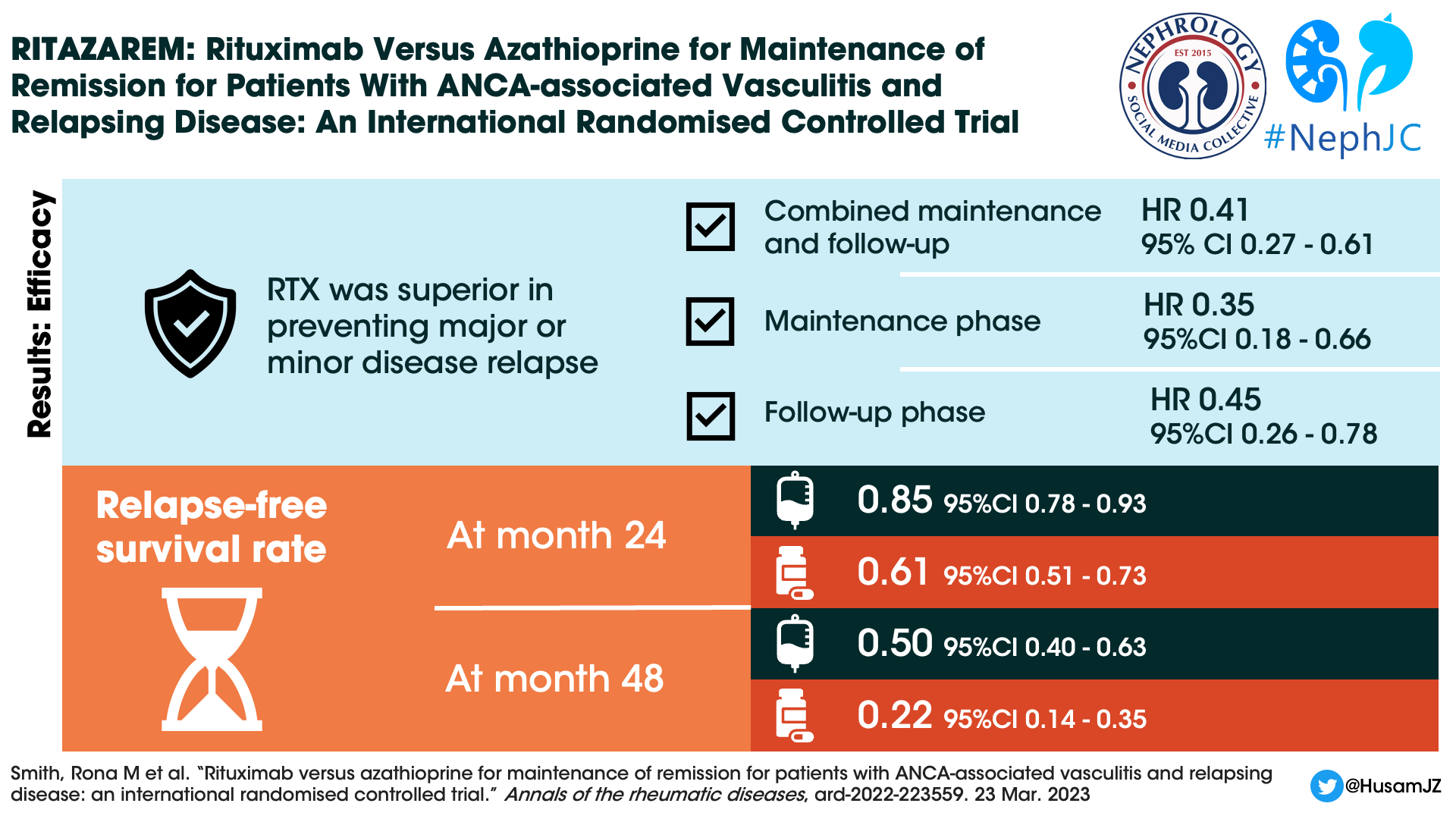

Primary Outcome

Through the combined maintenance and follow-up phases, rituximab was superior to azathioprine for the prevention of major or minor relapses (p < 0.001). The hazard ratio was 0.35 (95% CI 0.18-0.66, p=0.001) during the maintenance period and 0.45 (95% CI 0.26-0.78, p=0.004) during the follow up period.

Figure 2. Probability of relapse free survival, with month 0 representing randomization at the start of the maintenance phase rather than the nomenclature of month 0 being enrollment as used elsewhere in the paper. Note that each black arrow represents the timing of 1000 mg rituximab given. The dashed line represents the move to the follow-up phase. From Smith et al, Ann Rheum Dis 2023

Thirty-eight (45%) patients in the rituximab group experienced 11 major and 41 minor relapses. Sixty (71%) patients in the azathioprine group experienced 28 major and 61 minor relapses.

At 24 months, the relapse free survival rate was 0.85 (95% CI 0.78-0.93) for rituximab patients compared with 0.61 (95% CI 0.51-0.73) for the azathioprine patients. Only 5 patients in the rituximab group versus 11 patients in the azathioprine group experienced major relapses during the follow-up period.

In a multiple regression model, neither the glucocorticoid induction dose (high versus low), nor the ANCA subtype (PR3 versus MPO) influenced relapse risk. Individuals who entered the trial with major BVAS/WG items at relapse were less likely to experience a relapse during the trial.

Figure 3. Sub-group analysis. From Smith et al, Ann Rheum Dis 2023

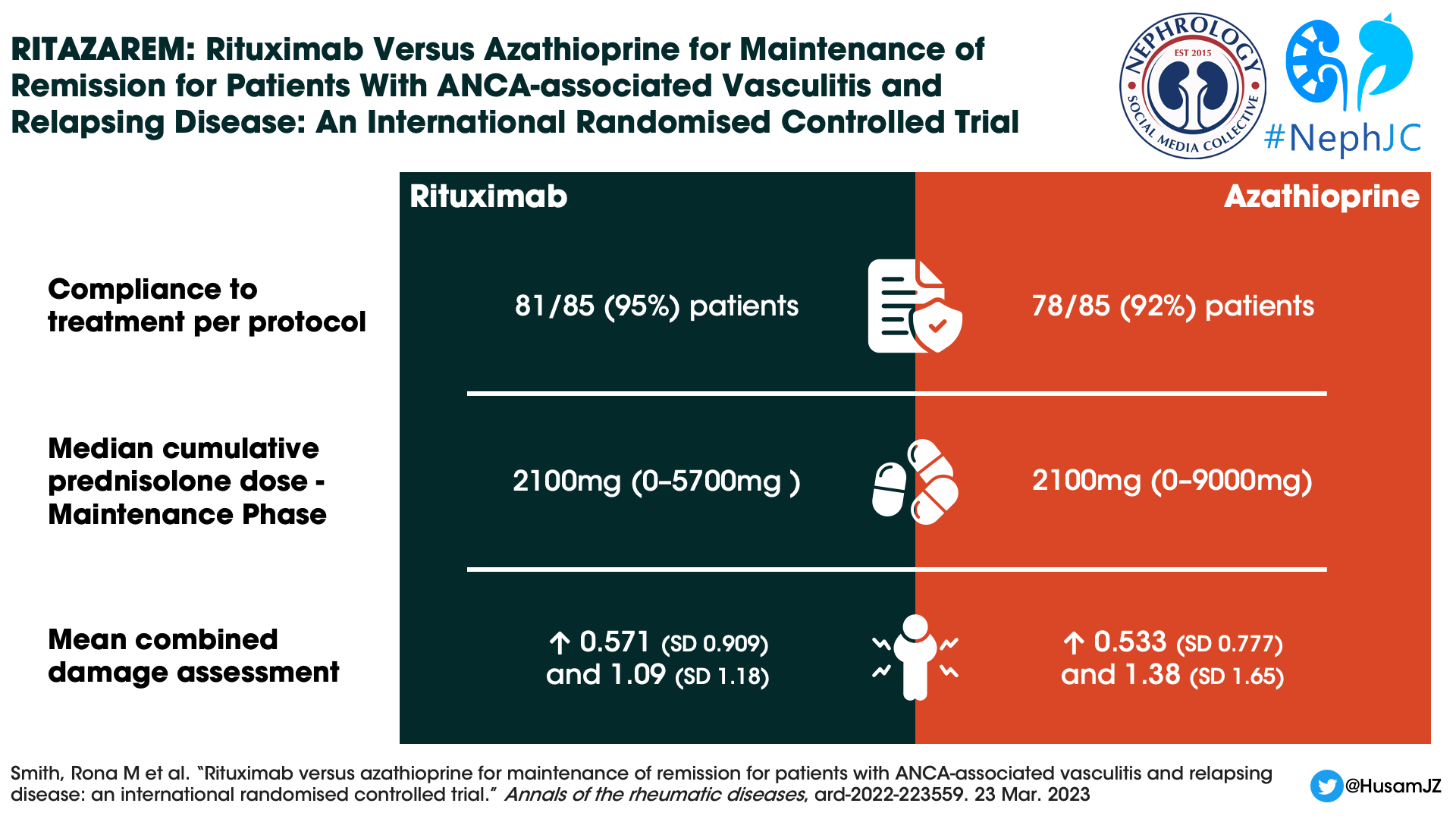

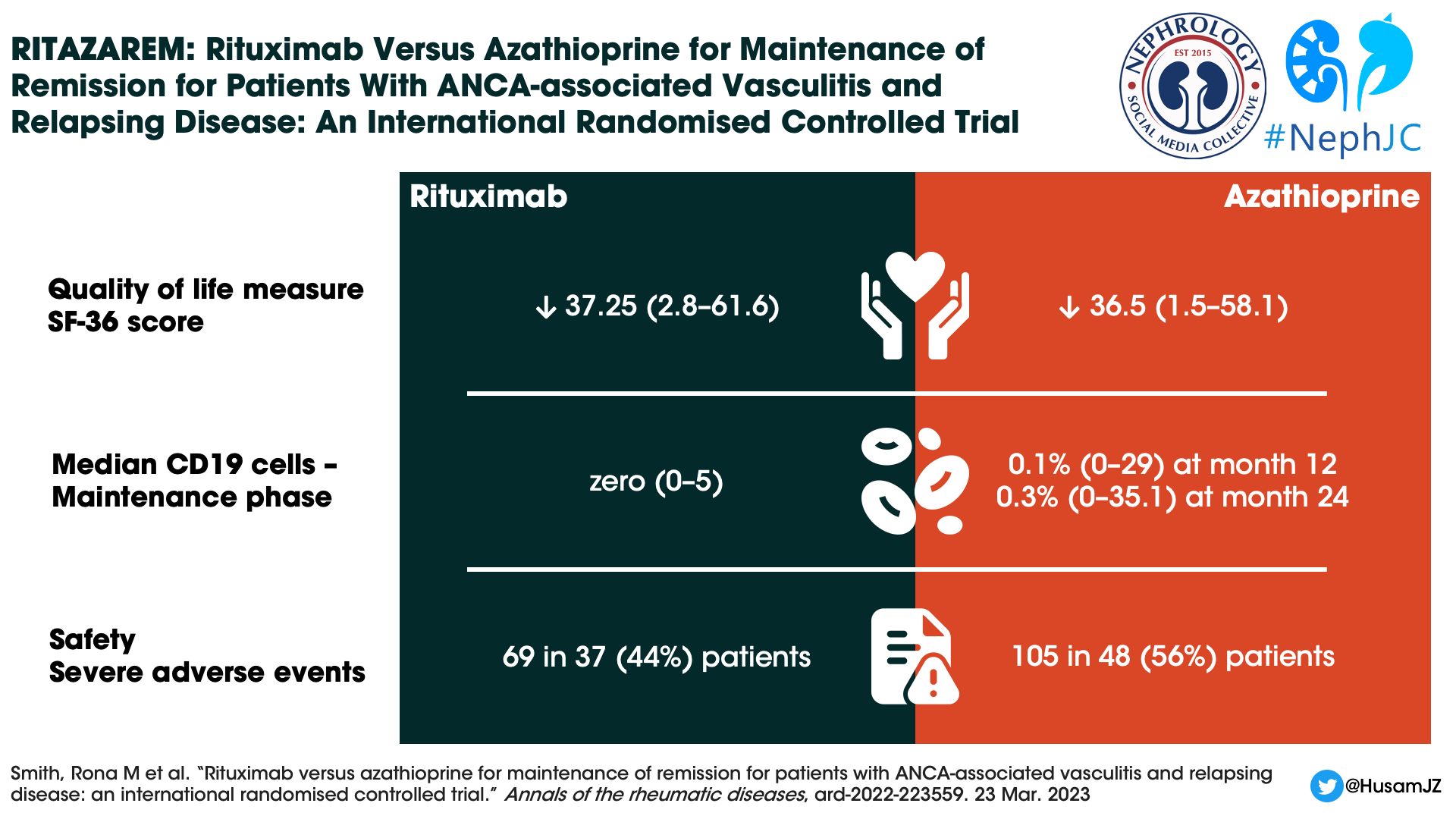

Despite the difference in relapse rates, no difference in quality of life measures could be demonstrated. Both groups maintained similar scores in physical and mental domains.

The median cumulative prednisolone dose was identical in both groups during the maintenance phase (median 2100 mg). Deviations from the protocol were common: 52% in the rituximab group versus 67% in the azathioprine group. At 24 months, when steroids were supposed to be discontinued, 29% of rituximab patients and 46% of azathioprine patients still received glucocorticoids at a dose of 2.28 mg and 2.8 mg respectively.

CD 19 positive B cell counts during the maintenance phase were 0×109 /L (0–3) in the rituximab group and 0×109 /L (0–5) in the azathioprine group. The median percentage of CD19 cells remained zero (0–5) in the rituximab group but increased to 0.1% (0–29) at month 12 and 0.3% (0–35.1) at month 24 in the azathioprine group. Surprisingly, during the follow-up phase the median CD19 cell counts were lower in the azathioprine group (see supplementary figure 3), though the authors comment this was confounded by the use of rituximab to treat relapses.

Supplementary figure 3. Percentage of CD19+ B cells throughout RITAZAREM, by treatment group. From Smith et al, Ann Rheum Dis 2023

Sixty-nine SAEs occurred in 37 (44%) patients in the rituximab and 105 in 48 (56%) in the azathioprine groups (Table 2). There was no difference in time to the first SAE between groups. Nineteen (22%) patients in the rituximab and 31 (36%) patients in the azathioprine groups experienced at least one SAE during the treatment period.

Table 2. Adverse events, from Smith et al, Ann Rheum Dis 2023

Discussion

Yet again, rituximab has convincingly defeated azathioprine in AAV, this time in patients with relapsing ANCA-associated vasculitis. It isn’t just more efficacious, it didn’t even fail on parameters like IgG levels <3g/L, that clinicians may have thought would be a difficult hurdle (though rituximab use for induction and rescue will have confounded this somewhat). Rituximab has reached the stage that if you have access to it for your patients, it is getting harder and harder to justify reaching for azathioprine. Even if you say that you’d never taper a high risk population off azathioprine after 2 years, you have to acknowledge that azathioprine was also solidly defeated throughout the maintenance phase.

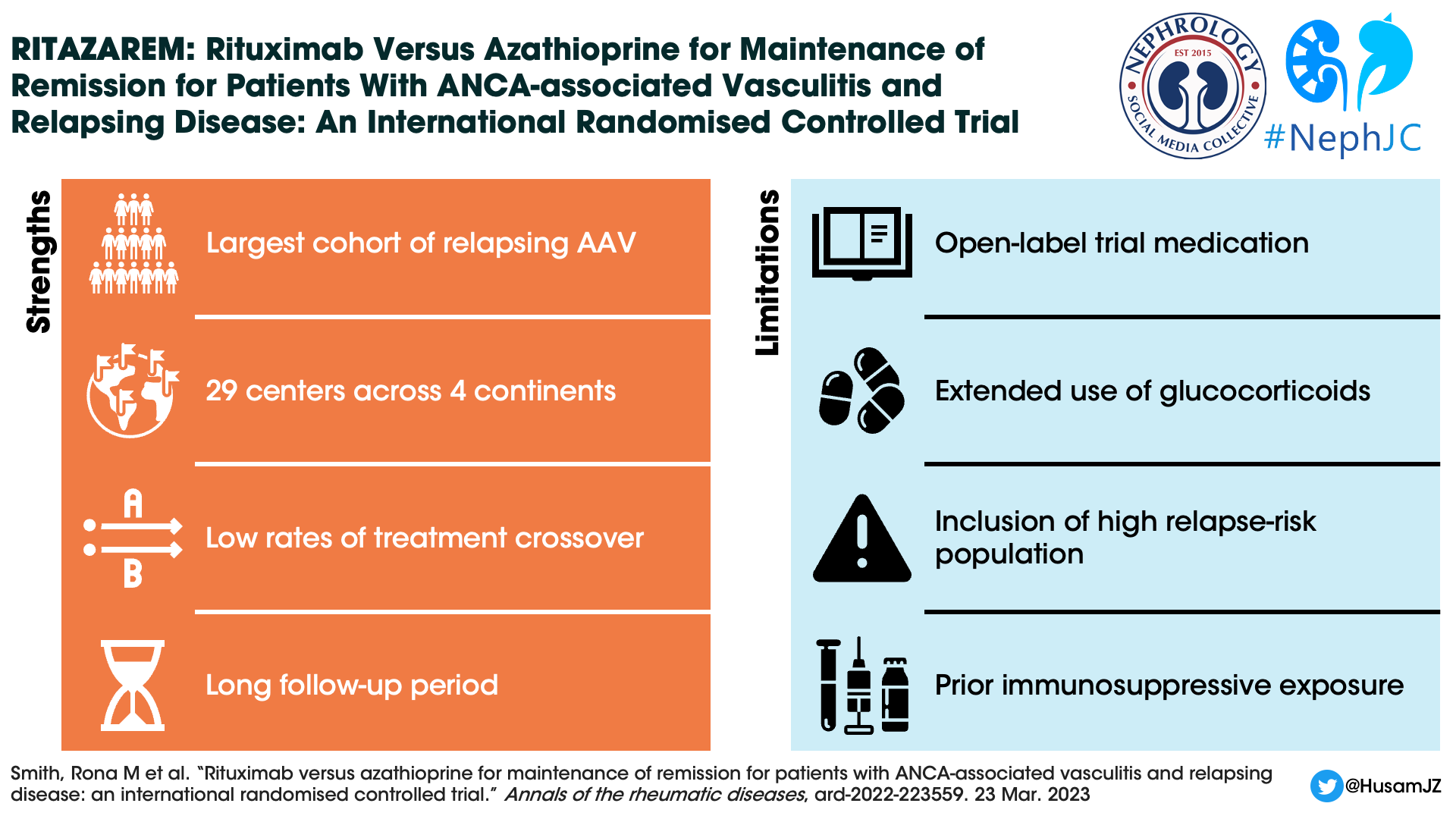

RITAZAREM was a well-performed trial from experts in the field, who must be congratulated on strong recruiting in a subset of patients with a rare disease. A major strength lies in it being the largest cohort of patients with relapsing AAV to ever be studied in a clinical trial, with results that will be broadly applicable.

A high proportion of patients (171/188 or 90%) in RITAZAREM achieved remission by 4 months, and it is also notable that 71% of patients received the low dose glucocorticoid regimen. The major source of previous prospective data on induction of remission for relapsing patients with AAV was from the RAVE trial. In RAVE it was observed that a higher rate of remission was achieved in 50 relapsing patients treated with rituximab when compared with 50 relapsing patients treated with cyclophosphamide. Thus, this new data further supports rituximab for induction in relapsing disease. Of note, the higher remission rate reported in RITAZAREM versus RAVE may be due in part to the different definitions of remission. In RITAZAREM, remission was defined as a BVAS/WG ≤1 with a prednisolone dose ≤10 mg/day. The RAVE trial observed a remission rate of 64% at 6 months, but required a BVAS/WG of zero and complete glucocorticoid withdrawal. Always beware comparisons of outcomes when they have moved the goalposts.

Infographic by Priti Meena

The MAINRITSAN 1 trial demonstrated superiority of rituximab over azathioprine for the prevention of relapse in patients receiving cyclophosphamide induction for AAV. The MAINRITSAN 1 trial used a dose of 500 mg at six month intervals. RITAZAREM focused on cases of relapsing AAV, which tend to have a higher likelihood of repeat relapse. We are not given the average number of times patients in RITAZAREM had relapsed before, but given ⅓ of them were still on oral immunosuppression after 7 years (or 5 years if you go by Table 1 in the initial report in Smith et al, ARD, 2020), one would guess many patients had relapsed more than once prior to the study, and therefore they were at high risk of relapse again.

It was previously observed that most cases of relapse occurred in 4-6 months following a dose rituximab induction, as measurable B cell activity tended to return 4 months after rituximab treatment. Thus, increasing the dosing frequency to 4 months was a logical step for this trial, especially given the high risk nature of the patients. The cumulative dose of rituximab used in RITAZAREM was over 3 times as high as MAINRITSAN 1, but amazingly no increased adverse events were observed. The rituximab dose was 1.5g in MAINRITSAN versus 5g in RITAZAREM. Though this study showed the efficacy of higher doses in a population at high risk of relapse, it didn’t prove that the larger doses (and higher expense, which despite going generic remains relevant in many healthcare systems) were necessary. Perhaps, if we truly gained extra disease suppression for ‘free’, and without added infections, it would be welcome. The MAINRITSAN 2 (Charles et al, ARD, 2018) approach of personalized rituximab administration based on reconstitution of CD19+ B lymphocytes or ANCA titers was not trialed here. Cautious use of higher cumulative doses of rituximab, for prolonged periods, may be necessary for high risk patients given the increased relapse rate observed after therapy was stopped, but inducing secondary chronic immunodeficiency remains a large concern.

In RITAZAREM, SAEs occurred in 14.3% of patients receiving rituximab, which was a lower rate than seen in the RITUXVAS trial, with 42% of patients with at least one SAE, and the RAVE trial, with 22% of patients experienced at least one severe adverse event. In the treatment of AAV, concomitant use of glucocorticoids is a major contributor to SAEs, especially infective risks, and two glucocorticoid regimens were permitted in RITAZAREM. The choice of glucocorticoid regimen was not randomized, and thus may have been subject to bias, so the relative efficacy of these two regimens cannot be completely analyzed. The fact that nearly ¾ of patients received low dose steroid induction may have played a role in decreasing SAEs. There is also the fact that more patients in the azathioprine arm had to deviate from the protocol as they could not be weaned off steroids. Being on the less effective medication to prevent relapse often leads to extra harm due to prolonged glucocorticoids, extra organ damage incurred upon relapse, or need for rituximab rescue therapy (which we are told occurred in the azathioprine arm often enough to confound the CD19+ B cell results, but figures are not provided).

Reading this publication in 2023, it feels like the only real criticism is that the results feel so expected. Maybe it’s because we’ve known the results since the presentation at ASN 2019! To be fair, RITAZAREM was designed prior to the results of MAINRITSAN 1 being published, and the population here is novel. However, considering how high the risk of relapse was in this population (as inferred from 19% of patients still being on azathioprine despite being 7 years since diagnosis, ⅓ being on some form of oral immunosuppression at relapse, mean of 25g* of cyclophosphamide needed in the past, and high PR3-ANCA proportions) it is hard to imagine many clinicians thinking, “Well, I’ll just try them back on azathioprine again after re-induction and hope for the best”. So, even though it was a fantastic trial, our guess is that clinical practice has already moved on to rituximab being the standard of care, rather than this trial being a practice changer.

Unfortunately, despite the higher doses of rituximab, relapses still occurred in 15% of patients treated with maintenance rituximab. In addition, there was a high risk of relapse after stopping either maintenance treatment, showing that even high dose rituximab did not sustain remission beyond treatment. The search for newer medications with prolonged AAV suppressive effects is ongoing.

*The RITAZAREM paper states mean prior cyclophosphamide at 25 g, though the paper on induction in RITAZAREM states median 9 g with range 0.15 - 301 g (!), so quite a skewed distribution.

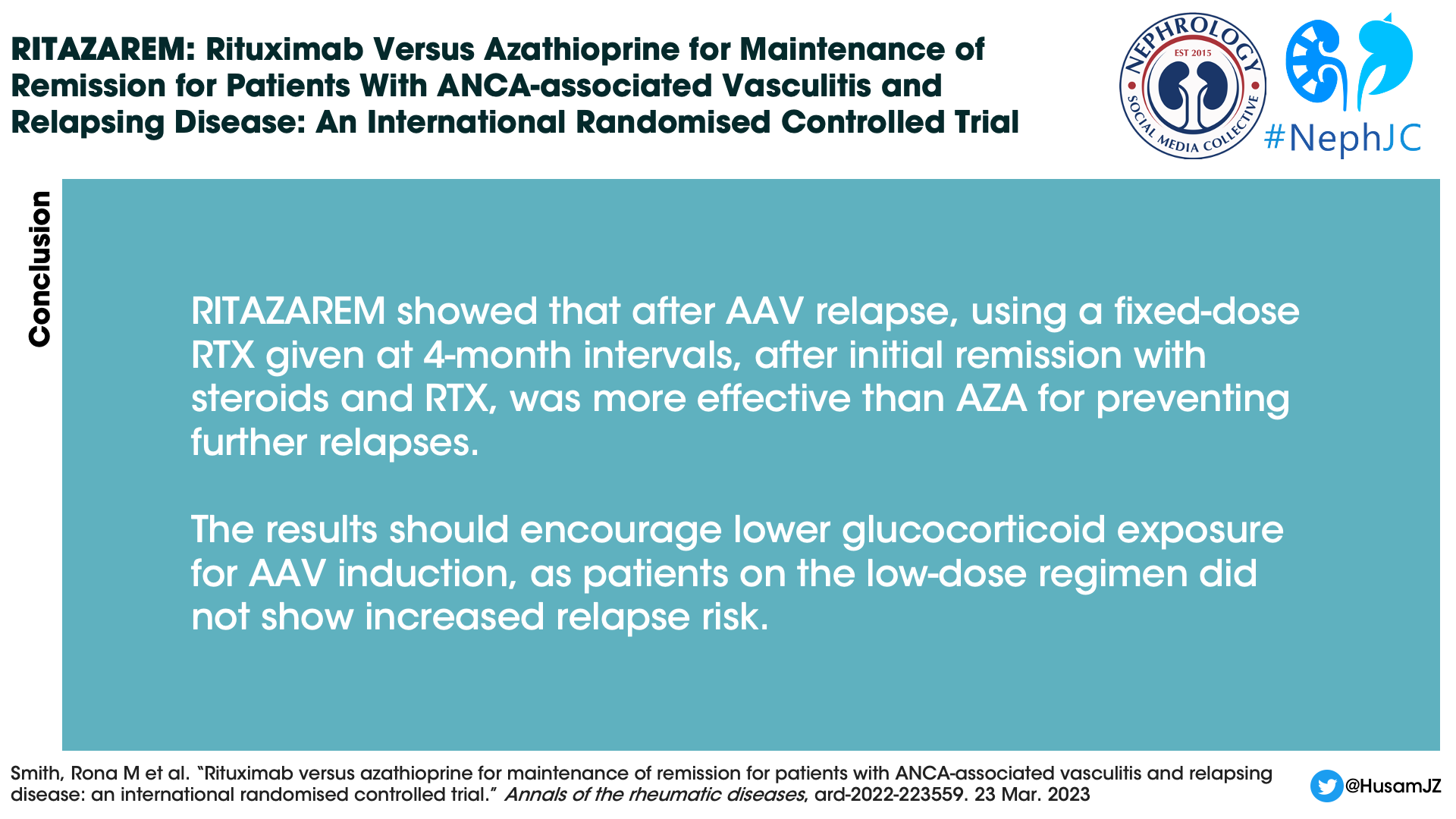

Conclusion

The RITAZAREM trial showed that after a relapse of AAV use of fixed dose rituximab given at 4 month intervals, after initial remission with steroids and rituximab, was more effective than azathioprine for the prevention of further relapse. The results should also encourage lower glucocorticoid exposure for AAV induction, as patients on the low dose regimen did not show an increased risk of relapse.

Summary prepared by

Muhammad Yasir Baloch,

Internal Medicine Resident

Florida State University,

Tallahassee Memorial Hospital

and

Nihal Bashir,

Nephrology specialist,

Seha Kidney care – AlAin,

UAE/Faculty internal medicine program

Tawam hospital Alain, UAE

NSMC interns, class of 2023

Reviewed by Jamie Willows, Cristina Popa, Brian Rifkin, and Jade Teakell

Header image by AI, with prompts from Evan Zeitler