#NephJC Chat

Tuesday Aug 4 9 pm Eastern

Wednesday Aug 5 9 pm IST

Wednesday Aug 5 9 pm BST

N Engl J Med 2020 Jul 16;383(3):240-251. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2000741.

Timing of Initiation of Renal-Replacement Therapy in Acute Kidney Injury

STARRT-AKI Investigators; Canadian Critical Care Trials Group, the Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society Clinical Trials Group, the United Kingdom Critical Care Research Group, the Canadian Nephrology Trials Network, and the Irish Critical Care Trials Group; Sean M Bagshaw, Ron Wald, Neill K J Adhikari, Rinaldo Bellomo, Bruno R da Costa, Didier Dreyfuss, Bin Du, Martin P Gallagher, Stéphane Gaudry, Eric A Hoste, François Lamontagne, Michael Joannidis, Giovanni Landoni, Kathleen D Liu, Daniel F McAuley, Shay P McGuinness, Javier A Neyra, Alistair D Nichol, Marlies Ostermann, Paul M Palevsky, Ville Pettilä, Jean-Pierre Quenot, Haibo Qiu, Bram Rochwerg, Antoine G Schneider, Orla M Smith, Fernando Thomé, Kevin E Thorpe, Suvi Vaara, Matthew Weir, Amanda Y Wang, Paul Young, Alexander Zarbock

PMID: 32668114

“We have a joke about kidney replacement therapy and AKI but we were wondering when to STARRT telling it”

Introduction

Although the timing for kidney replacement therapy (KRT) is obvious when severe complications of acute kidney injury (AKI) such as metabolic and fluid derangements are present, the hypothesis that an early initiation of KRT could improve outcomes by avoiding fluid overload, acid-base and metabolic complications has been present for a very long time. The rationale encouraging authors to address this question was based on two different goals: avoiding uremia and avoiding fluid overload.

Avoiding uremia

Teschan et al.1960 first proposed the concept of “prophylactic dialysis” in a report of 15 AKI patients who received dialysis before uremia developed (defined as non-protein nitrogen less than 200 mg/dl). The authors concluded: “Clinical manifestations of acute renal failure appear to be favorably influenced by prophylactic dialysis treatment”, which opened up the possibility of improving outcomes in AKI patients by using an early KRT strategy. Since, other authors have tested the hypothesis that avoiding uremia could show potential benefits. Gettings et al.1999 conducted a retrospective comparative study at a single trauma center analyzing the survival rate between early start of CKRT defined as BUN < 60mg/dl and late start defined as BUN >60 mg/dl. The authors found increased survival rate among early starters vs late starters. D Liu et al. 2006 analyzed data from the multicenter Program to Improve Care in Acute Renal Disease (PICARD) with the intention of evaluating the risk of death after an AKI diagnosis. In this study, they compared a group with a BUN < 76 mg/dl vs a group with a BUN > 76 mg/dl at the start of dialysis, demonstrating a higher BUN was associated with an increase in death. To complement the above study, Seabra et al.2008 analyzed the results of the previous studies in a systematic review and meta analysis. At that time 5 randomized controlled trials, 1 prospective and 16 retrospective comparative cohort studies were evaluated. The authors found great heterogeneity between studies, and reported a nonsignificant mortality risk reduction comparing early vs late strategies when analyzing randomized trials. However, when analyzing cohort and smaller studies (n < 100) the authors found significant mortality risk reduction for the early strategy group.

Avoiding Fluid overload

It is well known that fluid overload impacts survival among critically ill patients. It is therefore reasonable to hypothesize that avoiding fluid overload using early KRT will improve survival in these patients. Bouchard et al.2009 conducted a prospective multicenter observational study evaluating survival and recovery of kidney function related to fluid accumulation and found that among dialyzed patients, survivors had significantly lower fluid accumulation when dialysis was started compared to non-survivors. This finding suggested that avoiding fluid overload by starting early dialysis could improve survival.

The randomized control trials

The potential benefit of improved survival on early KRT strategy demonstrated in previous studies urged the need to perform adequately powered and well designed randomized control trials to address this question. In observational studies, patients are often grouped together based on the actual timing of initiation of KRT. Thus, it excludes patients who recovered without ever requiring KRT. These patients who never even needed KRT, might get exposed to KRT and its related complications (e.g. line insertion, hemodynamic fluctuation etc). So what have the RCTs shown so far?

First (Baumol et al, Crit. Care Med 2002) found no difference on survival when comparing early vs late hemofiltration in oliguric AKI in a 2 center RCT.

Then (Jamale et al, AJKD 2013) reported no benefit on in-hospital mortality and dialysis dependence at 3 months in community acquired AKI when dialysis was started early (BUN 70 mg/dl and Cr 7mg/dl) vs when it was started with an absolute indication.

Another single center randomized clinical trial evaluating mostly surgical patients ELAIN (Zarbock et al, JAMA 2016) reported lower mortality among patients that received KRT within 8 hours of developing AKI stage 2 + NGAL > 150 ng/ml vs patients that received KRT after 12 hours of developing AKI stage 3 or an absolute indication of KRT.

The same year the AKIKI trial (Gaudry et al, NEJM 2016) showed no difference in mortality between patients that received KRT within 6 hours of developing AKI stage 3 and patients that develop AKI stage 3 but had absolute indication. Both ELAIN and AKIKI were discussed in NephJC.

Finally the IDEAL-ICU (Barbar et al, NEJM 2018) a multicenter randomized trial showed no difference in mortality between septic patients that received KRT at 12 hours of developing AKI RIFLE stage F vs patients that received KRT after 48 hours of developing AKI RIFLE stage F.

Thus one trial (ELAIN) which compared early versus very early dialysis showed a benefit for mortality, whereas the other trials were negative, suggesting no benefit with early KRT, and potentially some harm. A review of the previous Landmark trials in KRT timing can be found in this post of the renal fellow network . All these and some trials were synthesized together in an individual patient-level metaanalysis a few months ago (Gaudry et al, Lancet 2020). From this study, which included 9 trials and 1879 patients, there was no difference in mortality at 28 days, but the outcomes of 90 day mortality, length of stay, dialysis dependence and adverse outcomes still showed significant heterogeneity. This leads us to the STARRT-AKI (Standard versus Accelerated Initiation of Renal-Replacement Therapy in Acute Kidney Injury) trial.

The Study

Design

Multinational, randomized, control trial involving critically ill patients with AKI, comparing accelerated strategy vs standard strategy of KRT initiation. 168 hospitals from 15 countries participated randomizing 3019 patients.

Study population

Inclusion criteria:

>18 year old

Admitted to the ICU with kidney dysfunction (Creatinine >1.13 in woman and >1.47 in men)

Severe AKI (doubling of serum Cr from baseline or a serum Cr of ≥ 4 mg/dl or a urine output of less than 6 ml/kg for the preceding 12 hours)

General exclusion criteria:

Emergency indications

Previous KRT Advanced CKD (GFR <20 mL/min/1.73 m2)

Uncommon causes of AKI (renal obstruction, RPGN, vasculitis, TMA, AIN)

Eligibility for randomization: Patients were eligible for randomization only after going through a two step evaluation.

Step 1 “Provisional eligibility”: All inclusion criteria and none of the exclusion criteria present.

Step 2 “Full eligibility”: Attending Physicians confirmed the absence of indication of immediate initiation or the need to deferral KRT, see below:

Randomization

Patients were randomly assigned in 1:1 ratio

Interventions

Accelerated strategy group: After randomization a 12 hour window was given for consent and initiation of KRT. Standard strategy group: KRT was not started until one or more of the following was present:

Potassium ≥ 6 mmol/L

pH ≤ 7.2

Bicarbonate ≤ 12 mmol/L

PaO2/FiO2 ≤ 200 + Volume overload

Persistent AKI for 72 hours after randomization

The delivery of KRT was standardized by providing recommendations according to international guidelines. Discontinuation occurred with recovery of kidney function, withdrawal of life support, or death.

Outcomes

Primary outcome: Death from any cause at 90 days

Key secondary outcomes: Dependence of KRTComposite: death or dependence of KRT and mayor kidney event

Prespecified secondary outcomes: Death at 28 days, KRT free days at 90 days, ventilator free days at 28 days, vasoactive free days at 28 days, hospitalization free days at 90 days, length of hospitalization, health related quality of life.

Statistical analysis

A modified intention to treat principle was used after exclusion of patients who had withdrawn consent, lost follow up, or had undergone randomization but were subsequently found to be ineligible. Sample size was 2866 assuming a 90 day mortality of 40% in the standard strategy group and aiming for a 90% power to detect a 15% relative between-group difference. The primary outcome was evaluated using a chi-square test and reported as a relative and absolute risk difference with 95% CI, it was also reported as an odds ratio with 95% CI and in a Kaplan-Meier time to event analysis. A prespecified subgroup analysis was performed for six variables: sex, baseline GFR, SAPS II, surgical admission, presence of sepsis and geographic region.

Funding Support

The trial was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research in partnership with Baxter, the National Health Medical Research Council of Australia, the Health Research Council of New Zealand, and the Health Technology Assessment Program of the United Kingdom National Institutes of Health Research.

Results

This sample size is larger than all the previous trials pooled together.

A total of 11852 patients met provisional eligibility. Of these patients, 3019 met full eligibility and were randomized to receive an accelerated strategy (1512 patients) or a standard strategy (1507 patients). After exclusion of patients that had withdrawn consent, lost to follow-up, or were found to be ineligible after randomization, 1465 and 1462 patients in the accelerated and standard strategy group respectively were included in the modified intention to treat analysis. This sample size is larger than all the previous trials pooled together.

Figure S2 from STARRT AKI, NEJM 2020

About 70% of the population were men, and 60% had sepsis. The serum creatinine at the time of randomization was ~ 3.5 mg/dL and the median urine output was about ~ 450 ml/24-hours. About 70% were on vasoactive support and three-quarters were being mechanically ventilated. The other features can be seen in table 1 and Table S5.

Initiation of KRT

Accelerated strategy group: 96.8 % of randomized patients were initiated with KRT. The median time of initiation was of 6.1 hours (3.9-8-8)

Standard strategy group: 61.8% of randomized patients were initiated with KRT. The median time of initiation was 31.1 hours (19-71.8)

See figure S3 for the actual timing and separation in the first 7 days after randomization.

Figure S3 from STARRT AKI, NEJM 2020

CKRT was used as the modality in about 70%, and IHD in about a quarter, with SLED/PIKRT representing the remaining 5%. Table S6 shows the difference in characteristics at the time of KRT initiation. Not only was there a nice separation of time, the patient who did inititate KRT in the standard strategy were

Excess 3 L in fluid balance

Sicker in most lab parameters (higher urea, creatinine, potassium, lower hemoglobin)

Had a higher SOFA score

With all this, one would expect the standard strategy would fare worse, right?

Primary outcome

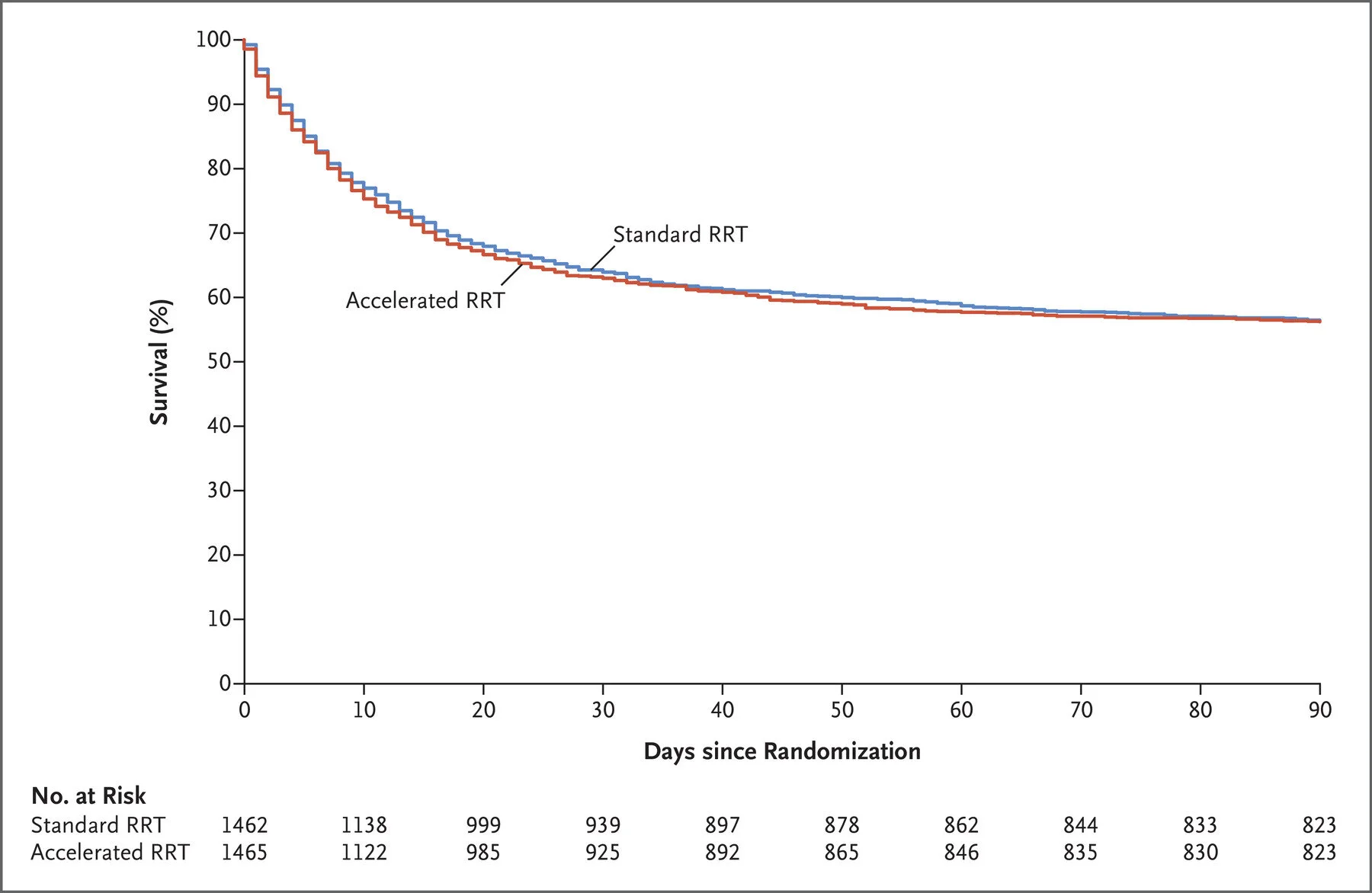

Death at 90 days occurred in 43.9% in the accelerated strategy and 43.7% in the standard strategy (relative risk, 1.00; 95% CI 0.93-1.09)

Figure 1 from STARRT AKI, NEJM 2020

Secondary outcomes

Higher dependence on KRT in the accelerated strategy 10.4% vs 6% (RR, 1.74; 95% CI 1.24 to 2.43)

Marginally fewer days of KRT in accelerated strategy -0.48 days; 95% CI, -0.82 to -0.14

Higher risk of rehospitalization in accelerated strategy RR, 1.23; 95% CI, 1.02 to 1.49

No difference was found in the composite outcome, death at 28-days, length of hospitalization, KRT-free days, ventilator-free days, vasoactive-free days, ICU-free days, hospitalization-free days and quality of life.

Table 2 from STARRT AKI, NEJM 2020

Subgroup analysis

No difference found for any of the six variables evaluated in the prespecified subgroup analysis. Note that even in the surgical ICU admissions, which was the patient population in ELAIN, the only positive RCT, there was no difference seen.

Figure 2 from STARRT AKI, NEJM 2020

Adverse events

Adverse events occurred in 23% in the accelerated strategy and 16.5% in the standard strategy group (RR, 1.40;95% CI, 1.21 to 1.62). The most common adverse events were hypophosphatemia and hypotension.

Table 3 from STARRT AKI, NEJM 2020

Discussion

For many, this trial lays to rest a long-held suspicion that early initiation of KRT benefits critically ill patients with severe AKI. While previous studies demonstrated mixed results, the methodological characteristics and robust results of the STARRT-AKI trial build a strong case that an early KRT strategy in critically ill patients does not improve outcomes, especially mortality. See how it compares to the other major trials in this table:

Potential harms

It's also important to mention that there was much more KRT provided to the early start group that consumed resources and exposed patients to adverse events without obtaining any benefit whatsoever.

Why would this occur? Surely early dialysis initiation avoids the volume overload and uremic toxic accumulation that we discussed above. How can this not be good? Look again at how many of the patients in the ‘standard’ strategy needed KRT at all. Though some participants did die before initiation of KRT, about 40% did not need KRT at all. Avoiding KRT means they avoided the complications of KRT: no hypotension, no line related complications, no hypophosphatemia etc. Presumably some of these hypotensive episodes may have actually caused kidney damage, hence the higher dialysis dependence in the accelerated strategy. This line of reasoning also explains the discordant result of the ELAIN trial, in which, both groups started dialysis. The benefit of standard (or late) initiation of dialysis in AKI is in avoiding it for those who would never have needed it.

The strengths of this trial were the large sample size, the generalizability gained by the multinational, multicenter design, the deliberate enrollment of patients for whom the decision of initiation of KRT was uncertain and the standardisation of the prescription by providing evidence informed recommendations.

The limitations of the trial were: The risk of introducing heterogeneity in both groups by using clinical criteria to decide if KRT indication was uncertain and therefore decide if it was eligible for randomization. Also physicians were afforded liberty to start dialysis at their discretion in the standard strategy group, which introduced heterogeneity in start times. Finally the interpretation of the adverse events in the early strategy could be explained by the prespecified focus on reporting events and the larger number of patient days of therapy.

Conclusion

The multinational STARRT-AKI trial is the largest trial to inform us about the timing of KRT initiation in critically ill patients. The trial demonstrates a sound methodological approach while more accurately reflecting current practice in critically ill patients with AKI. It is time we consider that the STARRT-AKI results are the definitive and final answer to a 60 year question.

Summary prepared by Pablo Galindo MD