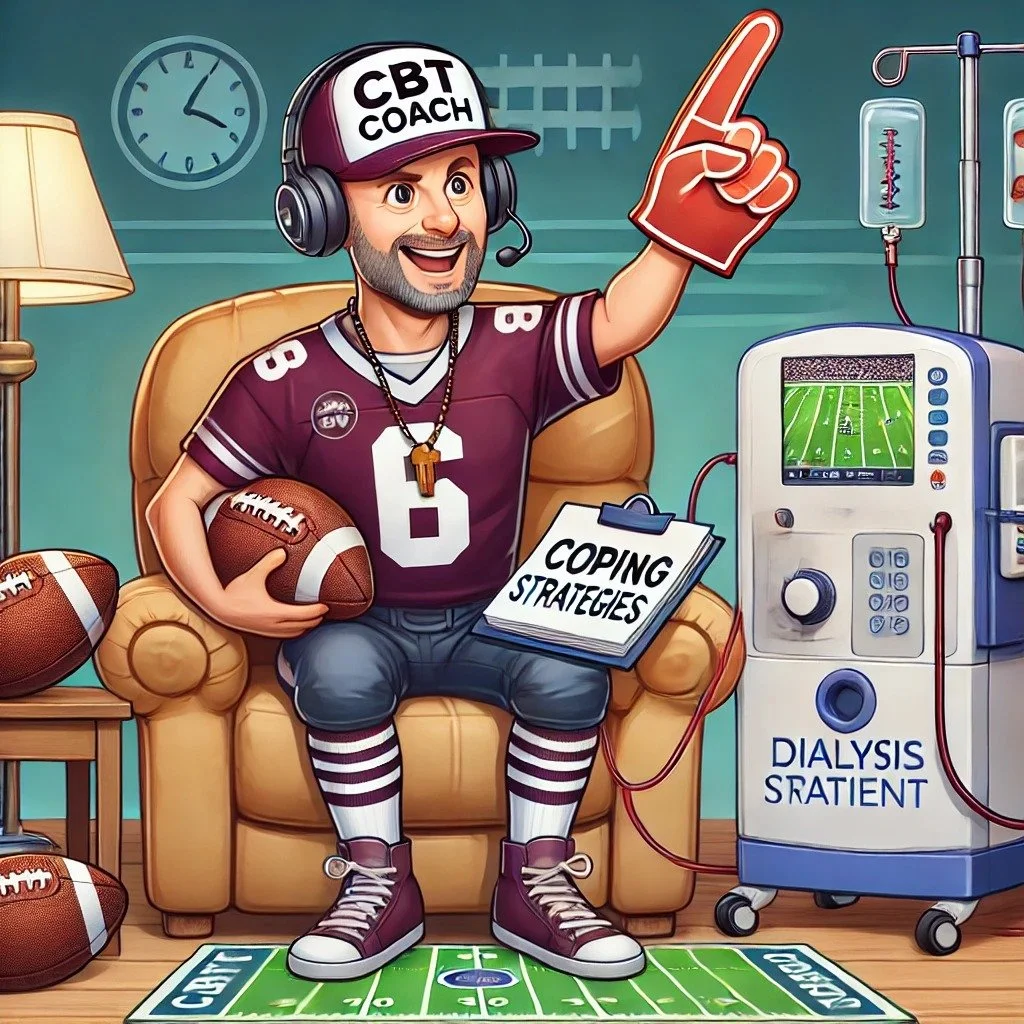

Edgar created this visual abstract, for the AJKD blog. Why mess with something so good?

Being Mortal: Chapter Two

Edgar Lerma, [EL] Chicago nephrologist and father of #NephPearls worked with Joel on this summary of the second exciting chapter of Being Mortal.

Chapter Two: THINGS FALL APART

Chapter Two looks at how life and death have changed with modernity. Gawande describes how the lifespan has increased from around 60 in the 1930’s to somewhere in the 80’s today. But he goes on to emphasize that the life span does not quite capture how much the shape of mortality has changed. He points out that modern medicine has dramatically reduced childhood mortality. Please look at the story of John Leal and his role in reducing infant mortality by 74% by inventing the concept of chlorinating city water.

Gawande describes the change in the ‘trajectories of life.’ In the past, life appeared to be a continuum, curtailed by disease or injury. This could happen at anytime from infancy, to childhood, to adulthood to older age. The risk was relatively flat, one day you were alive and the next you were kicked by a horse, or infected with influenza, or had a heart attack, and the next day you were dead. Modern medicine has changed that trajectory in a couple of different patterns. The most successful medical practices delay or prevent acute deaths. Treatment of serious infections or trauma care are good examples. Even some cancer therapy is successful at delaying the onset of decline without changing the basic pattern of health until a final acute loss:

“People with incurable cancers, for instance, can do remarkably well for a long time after diagnosis. They undergo treatment. Symptoms come under control. They resume regular life. They don’t feel sick. But the disease, while slowed, continues progressing, like a night brigade taking out perimeter defenses. Eventually, it makes itself known, turning up in the lungs, or in the brain, or in the spine, as it did with Joseph Lazaroff. From there, the decline is often relatively rapid, much as in the past. Death occurs later, but the trajectory remains the same.”

But for others, including those with chronic and progressive diseases, the trajectory has ups and downs, and following every deterioration, any recovery is incomplete and the overall trend is accumulating burden of illness. A classic example is chronic kidney disease. It is a chronic and progressive disease marked with episodes of AKI that further reinforce and accelerate the decline. People become weaker and weaker with incomplete recovery.

The effect of medicine has also introduced (or made more prevalent) a new type of death, a third pattern, a pattern not influenced by acute or chronic disease but just a slow withering decline, death by old age. Gawande spends a few great paragraphs describing the normal deterioration of aging and medicines frustration in dealing with it. Some facts:

- By age 60, people in industrialized countries have lost on average a third of their teeth.

- “As we age, it’s as if the calcium seeps out of our skeletons and into our tissues.”

- More than half of people develop hypertension by age 65

- Peak cardiac output occurs at age 30 and deteriorates after that

- By age 85, 40% of people have textbook dementia

This resonates with my [EL] CKD practice. I am repeatedly explaining that from age 40 onwards kidney function deteriorates as pat of normal aging. Furthermore, uncontrolled diabetes, hypertension, along with acute illness, accelerates this decline. My job, all of our jobs, as kidney specialists, is to slow this inevitable decline.

Gawande emphasizes that this deterioration is normal and unavoidable. We hold up the exceptional 97-year old marathoner as something to strive for rather than a story of remarkable genetic luck.

He then describes various theories about aging and different models to explain why we age. He looks at models of aging from complex systems to genetics. He describes the cellular mechanics of aging in skin, hair, and the eyes. It is a fascinating trip through the biology of aging.

As part of this tour we are introduced to Dr. Felix Silverstone a senior geriatrician at Parker Jewish Institute in New York. He is introduced as an expert geriatrician with over a 100 publications. He is is however old and now experiencing what he spent a career studying.

These societal changes bring about two revolutions: a “biological transformation” of the course of one’s life and also a “cultural transformation” of how one thinks about that course.

One of the societal changes of modernity has been the ‘rectangularization’ of the pyramid of life.

n the past, the elderly tended to be outnumbered by the younger generation; however, as people tend to live longer, there are almost equal numbers represented by the young and the elderly. This has wide ranging implications. For one, the number of people supporting retirees is shrinking compared to the number of retirees. The time when a large working population is supporting a small number of retirees is gone.

The second issue that he brings up is that medicine has done a poor job preparing for the changing demographics. The number of geriatricians with the skill and experience in handling such patients is not keeping up with the need. Structural changes in medicine perversely are causing geriatric centers to close in the face of increasing need.

“Although the elderly population is growing rapidly, the number of certified geriatricians the medical profession has put in practice has actually fallen in the United States by 25 percent between 1996 and 2010.”

As a subspecialist, I [EL] tend to view my patients in a reno-centric point of view. I feel that I am very good at diagnosing and treating kidney related problems. However, I do realize that as I fix my patients’ kidney related issues, e.g., blood pressure control, diabetes control, etc., there are some on the problem list that won’t ever get resolved, e.g., the lower extremity edema of my CHF patient with LVEF ~ 10% or the salt intake of my patient who depends on Meals on wheels, etc.

Oftentimes, my untrained mind, wonders why is it that whenever I see elderly patients, it’s as if the primary care provider hasn’t adjusted their BP meds or checked their proteinuria, etc. Gawande addresses this by explaining that geriatricians have a unique point of view. An example is a story about Dr. Juergen Bludau, a geriatrician, who paid more attention to an elderly patient’s feet, and if she is able to bend over to clean them. It all boils down to the idea that this intensely practical approach translates into decreased falls. Dr Bludau said that “the job of any doctor is to support quality of life: as much freedom from the ravages of disease as possible, and retention of enough function for active engagement in the world.” Gawande describes how effective the work of geritricians is by explaining a landmark randomized controlled trial of geriatric versus usual care.

“Within eighteen months, 10 percent of the patients in both groups had died. But the patients who had seen a geriatrics team were a quarter less likely to become disabled and half as likely to develop depression. They were 40 percent less likely to require home health services.

These were stunning results. If scientists came up with a device—call it an automatic defrailer—that wouldn’t extend your life but would slash the likelihood you’d end up in a nursing home or miserable with depression, we’d be clamoring for it. We wouldn’t care if doctors had to open up your chest and plug the thing into your heart. We’d have pink-ribbon campaigns to get one for every person over seventy-five. Congress would be holding hearings demanding to know why forty-year-olds couldn’t get them installed. Medical students would be jockeying to become defrailulation specialists, and Wall Street would be bidding up company stock prices.

Instead, it was just geriatrics. The geriatric teams weren’t doing lung biopsies or back surgery or insertion of automatic defrailers. What they did was to simplify medications. They saw that arthritis was controlled. They made sure toenails were trimmed and meals were square. They looked for worrisome signs of isolation and had a social worker check that the patient’s home was safe.

How do we reward this kind of work? Chad Boult, the geriatrician who was the lead investigator of the University of Minnesota study, can tell you. A few months after he published the results, demonstrating how much better people’s lives were with specialized geriatric care, the university closed the division of geriatrics.”

The chapter closes by rejoining Felix Siverstone as he ages and enters a nursing home with his wife. He thrives in this environment and even starts a journal club for retired physicians (NephJC geriatric edition!)

The chapter is a great set up for the rest of the book, it informs the readers, sets the stage, raises the stakes. The tension is set.