The non-steroidal mineralocorticoid antagonists (ns-MRA) are suddenly everywhere. Finerenone, after playing sweet music in diabetic kidney disease, demonstrated success in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) in the FINEARTS HF trial, and shows consistent effect in the pooled FINEHEARTS analysis being discussed on #NephJC. These benefits, while not surprising to anyone following the field, have not been reported with spironolactone, or eplerenone. Does this imply that ns-MRAs are different and provide benefit while avoiding the harms of old fashioned steroidal MRAs? Let’s take a deeper dive.

ns-MRA development

The best history of the development of the ns-MRA with finerenone as the initial molecule is from the NephMadness scouting report from Micah Schub, with Matt Luther. Some of the key nuggets include that these were devloped following the observation that dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers (e.g. amlodipine) have mineralocorticoid antagonist properties (see Dietz et al, Hypertension 2008). The advantage of ns-MRA is that they do not bind as well to the progesterone, androgen, or glucocorticoid receptor as well - but bind to the mineralocorticooid receptor as well as spironolactone (and better than eplerenone does?).

The appropriate trials (ARTS-DN, followed by the symphony of FIDELIO, FIGARO) then followed, clearly establishing the beneficial role of finerenone in diabetic, proteinuric kidney disease.

Does Spironolactone have the same effects as Finerenone?

An excellent summary of this topic is again provided in the 2023 Nephmadness scouting report from Micah Schub and Matt Luther. Over 2 decades ago, the addition of spironolactone to ACE inhibition was reported to show a reduction in proteinuria (Chrysostomou and Becker, NEJM 2001).

Table from Chrysostomou and Becker, NEJM 2001

Unfortunately, spironolactone remained the neglected step child. Despite the study above, and subsequent small trials, all we could say was that the addition of spironolactone reduces proteinuria, increases hyperkalemia rates, and the effects on clinical outcomes is uncertain (Navaneethan et al, CJASN 2009). Notably the 11 trials included in the 2009 systematic review include a massive 991 patients, less than a tenth from the combined FIDELITY numbers. Even in the hypertension literature, it was ignored as a first line option in ALLHAT (Furberg et al, JAMA 2002) despite being approved in 1960 by the FDA at the same time as chlorthalidone. Even more heart wrenching was the TOPCAT trial of spironolactone in HFpEF (Pitt et al, NEJM 2014). Due to trial shenanigans in Russia and Georgia (possible inclusion of ineligible patients, intervention groups not even receiving spironolactone, and uncertain outcome ascertainment) nicely detailed here (Pfeffer and Pitt, NEJM Evidence 2022), the official, hard EBM line remained that spironolactone does not work in HFpEF. This is despite the North American TOPCAT data showing a clear benefit (Pfeffer et al Circulation 2014). That has left spiro-stans like us repeatedly saying (to whomever will listen, often just reassuring ourselves) that ‘I am sure spironolactone is just as good as finerenone’ and that the ‘right spironolactone trial just has not been done yet’! But that has changed now.

Spironolactone in Transplant: the SPIREN trial

Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2024 Jun 1;19(6):755-766. doi: 10.2215/CJN.0000000000000439. Epub 2024 Feb 27.

Effect of Spironolactone on Kidney Function in Kidney Transplant Recipients (the SPIREN trial): A Randomized Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial

Line A Mortensen, Bente Jespersen, Anne Sophie L Helligsoe, Birgitte Tougaard, Donata Cibulskyte-Ninkovic 3, Martin Egfjord, Lene Boesby, Niels Marcussen, Kirsten Madsen, Boye L Jensen, Inge Petersen, Claus Bistrup, Helle C Thiesson

PMID: 38416033

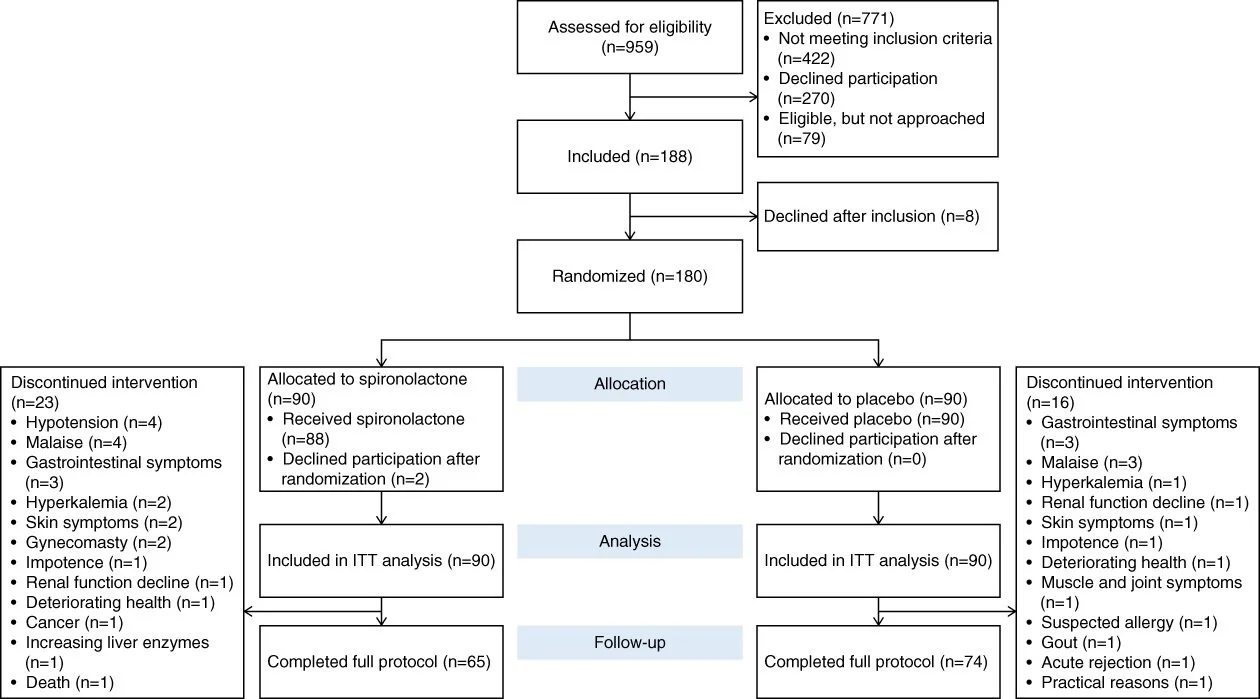

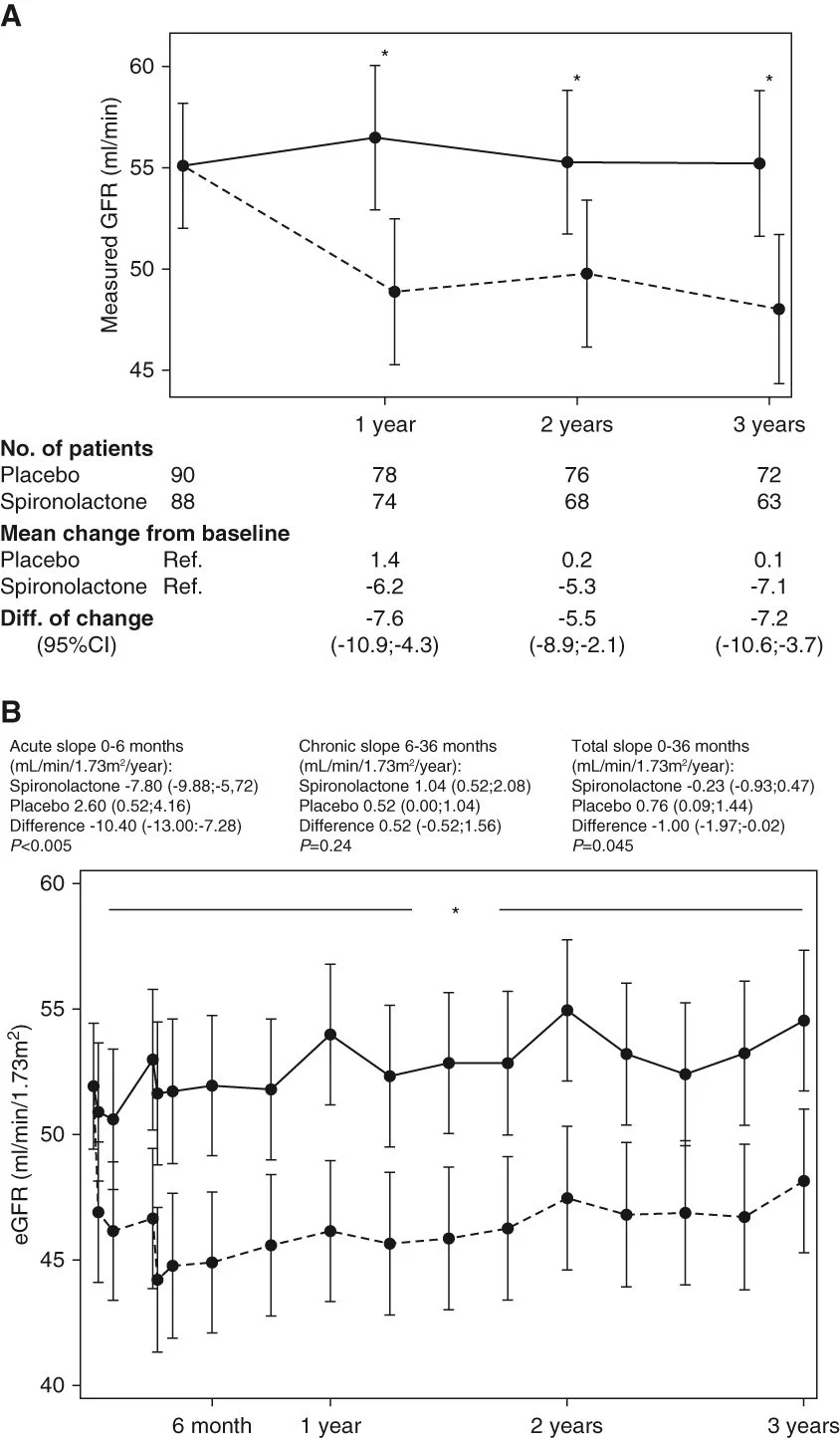

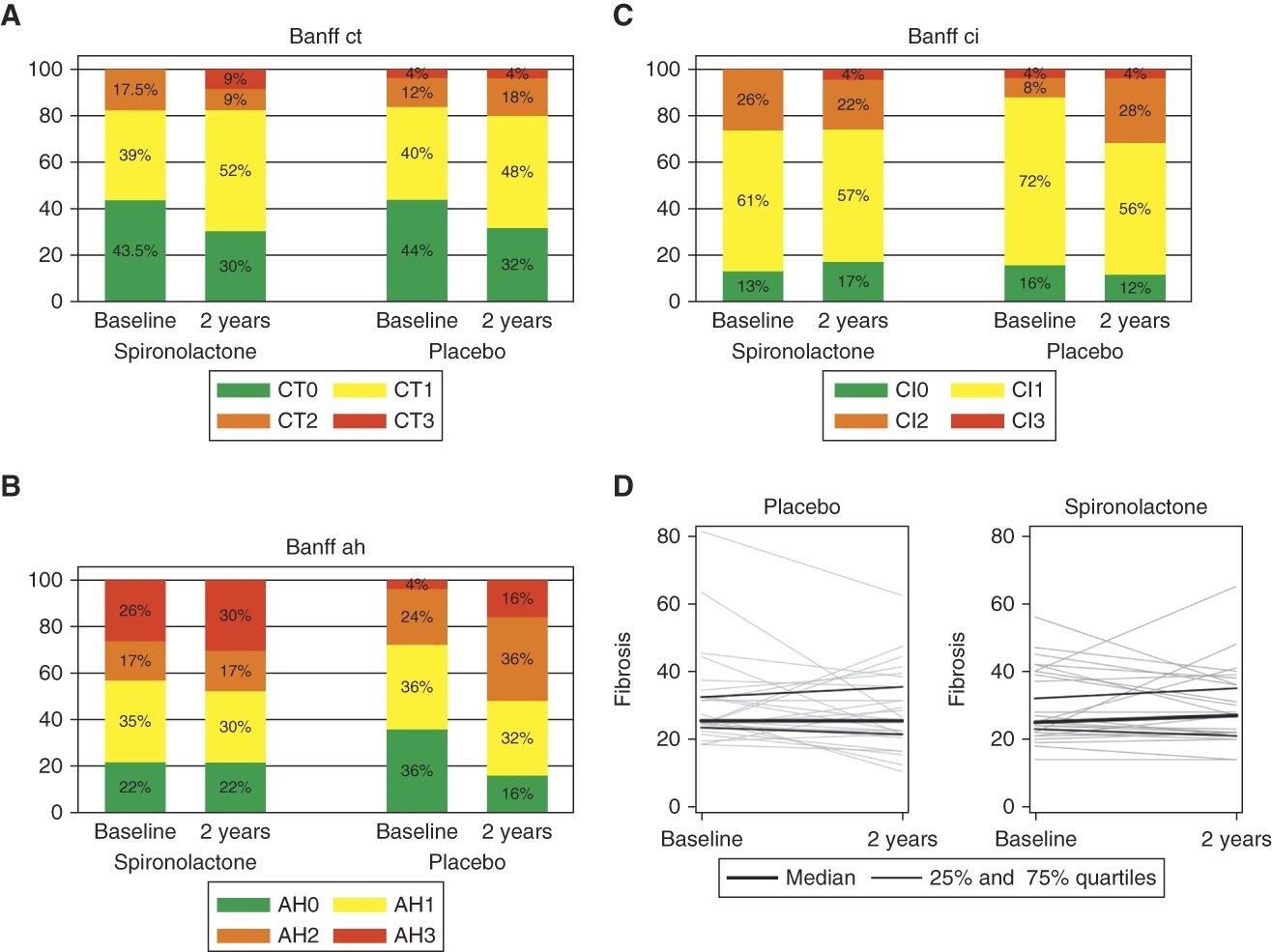

The SPIREN trial was a double blind RCT done at 4 Danish centres, comparing spironolactone to placebo in 180 kidney transplant recipients. The eligibility required these to have a creatinine clearance (with 24 hour urine collections!) of > 30 ml/min, a serum K < 5.5 with no K binder use, and proteinuria < 3 g/day. Notably this is different compared to the finerenone DKD trials which were open to baseline and subsequent use of K binders, and had a minimum proteinuria requirement as well (and allowed in people unless ACR > 5000 mg/g). The primary outcome was a difference in (measured, using nuclear methods) GFR at 3 years, powered for a very optimistic 5 ml/min difference. An interesting secondary outcome was the amount of interstitial fibrosis at 2 years based on protocol biopsies (note one of the purported mineralocorticoid antagonist MoA being the anti-fibrotic effects in the heart). Spironolactone was started at 25 mg daily and increased to 50 mg at 3 months if tolerated.

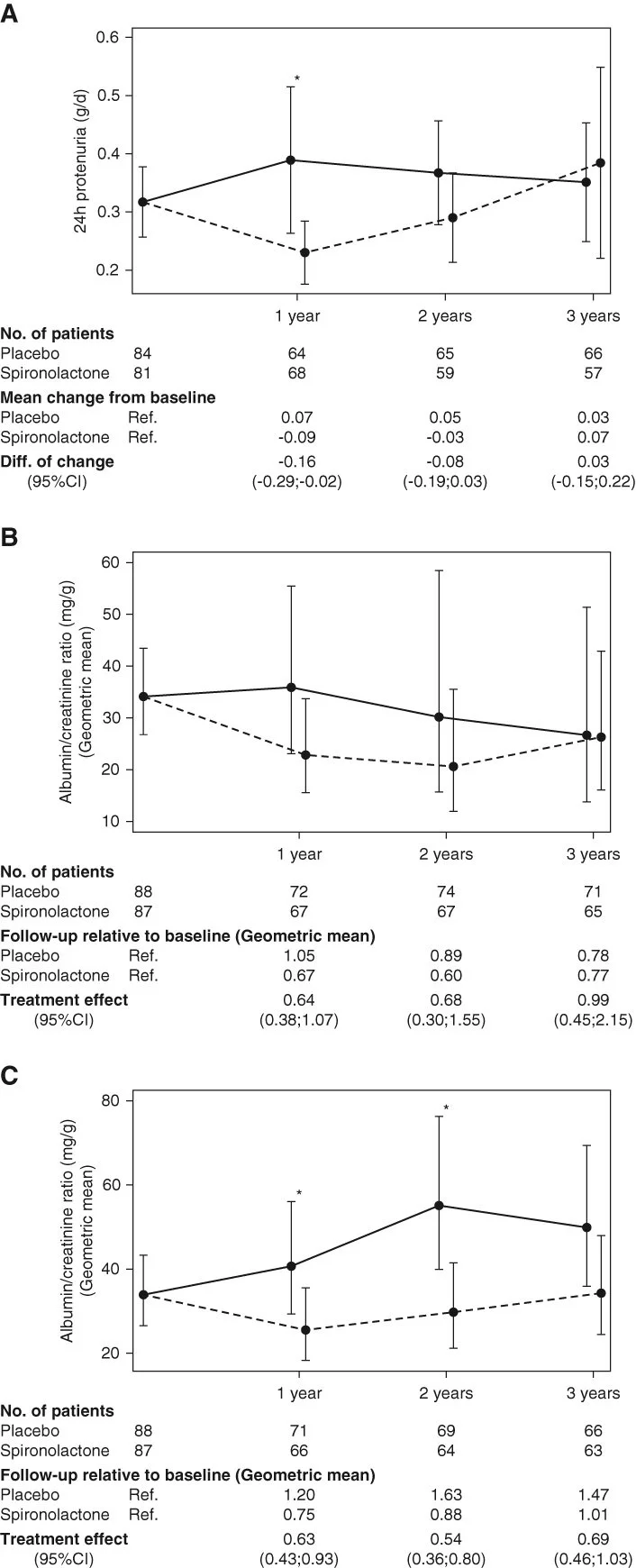

The population included had a mean age ~50 years, with less than 30% having diabetes, GFR just under 60, and little albuminuria with median ACR being ~ 30 mg/g. As expected, spironolactone reduced BP and increased serum potassium over the three years, but the albuminuria reduction that was seen at 1 year was not sustained at 2 or 3 years. The latter aspect is more clear when one considers the low baseline levels of albuminuria - and that a sustained effect was observed in the subgroup when participants with no albuminuria were excluded (Figure 3C). After all, one cannot reduce albuminuria if there is no albuminuria.

As far as clinical outcomes are considered, spironolactone caused the expected GFR dip initially, but then the chronic GFR slope remained very similar between the two groups, such that there was no benefit noted. There was no difference in the allograft fibrosis either. Interestingly there was little hyperkalemia (no hospitalizations, and only 4 who required dose reductions of spironolactone), and the number of dropouts was higher in spironolactone (26% versus 18%).

So does this mean that spironolactone, like RAS inhibition, does not work in the kidney transplant settings possibly since the mechanism of kidney function loss is not just RAAS mediated? (Hiremath et al, AJKD 2017). Or could it be that this population was low risk and the benefit of spironolactone requires an underlying combination of diabetes, albuminuria, and/or progressive GFR loss to manifest?

Figures from the SPIREN-D trial

Spironolactone in CKD: the BARACK trial

Nat Med. 2024 Sep 30. doi: 10.1038/s41591-024-03263-5. Online ahead of print.

Low-dose spironolactone and cardiovascular outcomes in moderate stage chronic kidney disease: a randomized controlled trial

F D Richard Hobbs, Richard J McManus, Clare J Taylor, Nicholas R Jones, Joy K Rahman, Jane Wolstenholme, Sungwook Kim, Joseph Kwon, Louise Jones, Jennifer A Hirst, Ly-Mee Yu, Sam Mort; BARACK-D Investigators; BARACK-D Investigators; Regional coordinating center teams

PMID: 39349629

The BARACK-D trial results dropped last week and were immediately seized by finerenone fans to state that ns-MRA are special. That indeed might be true, but this trial is not the right one to help draw that conclusion. Check out Josh Waitzman’s thread, as well as replies to Nayan Arora’s tweet which was hijacked by a couple of Spiro-stans.

The BARACK-D trial was a pragmatic open-label with blinded endpoints trial funded by the UK NHS and MHRA and conducted in the UK primary care setting across 329 general practice centers. They included participants with CKD defined as an eGFR between 30 and 49 ml/min/1.73m2. Notable exclusion criteria were a serum K > 5 mmol/L and an ACR > 70 mg/mmol (~ 600 mg/g). Diabetes was not required (though type 1 DM was an exclusion) and heart failure (clinical diagnosis or EF < 40%) was another exclusion. Spironolactone was started at 25 mg daily by their usual doctor and compared to usual care. There was no run-in period, and there was no additional dose titration. Spironolactone dose was reduced or it was stopped for safety reasons, however:

Reduced to alternate days if K 5.5 to 5.9 mmol/L

Stopped for a week if K 6 - 6.5 mmol/L and then restarted at alternate days

Stopped entirely if K > 6.5 mmol/L

Also stopped if GFR drop > 20% from last visit or 25% from baseline

There is no mention on the use of K binders to ameliorate the effects of hyperkalemia (unlike famously in FIDELIO - see Waitzman et al AJKD 2021, table below).

The primary outcome in BARACK-D was first occurrence of MACE, with an anticipated effect size of 20% reduction, and 13% discontinuation rate thus requiring just over 3000 participants.

Since the trial recruited at the peak of the COVID pandemic, only 45% recruitment was achieved at 1372 included in the final analysis (versus 3022 planned). The mean eGFR was just under 45, with about a quarter having diabetes and albuminuria at a measly ACR 1.5 mg/mmol (~12 mg/g). Just under 80% were on RAS inhibition and only 4 participants of 1372 were flozinated. Given the conservative criteria for continuing spironolactone, only a third of patients continued taking spironolactone beyond 6 months, with a median time from randomization to withdrawal from treatment being 3.2 months (IQR: 0.98–18.1). Due to COVID, only 88.0% of participants completed the year 2 study visit, compared to 95.0% at 6 months. Additionally, at the 3-year follow-up, only 71.1% of participants had a systolic blood pressure recorded and 71.4% an eGFR recorded.

Keeping this in mind, one will not be surprised that spironolactone did not even reduce BP (difference 1. 7 mmHg at 3 years) or albuminuria. And the primary outcome followed in a similar vein. The event rates ( 16-17%) were similar to FIGARO (~ 14%) but there was no difference between groups. None of the secondary clinical outcomes were different. Hyperkalemia (25%) and hypotension (7%) as well as the GFR fall (35%) triggering spironolactone stoppage were quite common.

The broad eligibility criteria - with low levels of DM and albuminuria, little serious effort to deal with hyperkalemia and conservative stoppage rules can be blamed for the lack of demonstrable benefits of spironolactone. On the other hand, one can confidently say that non-selective use of spironolactone in CKD patients is unlikely to be of benefit.

Figures from the BARACK-D trial

Pragmatic versus Explanatory trials

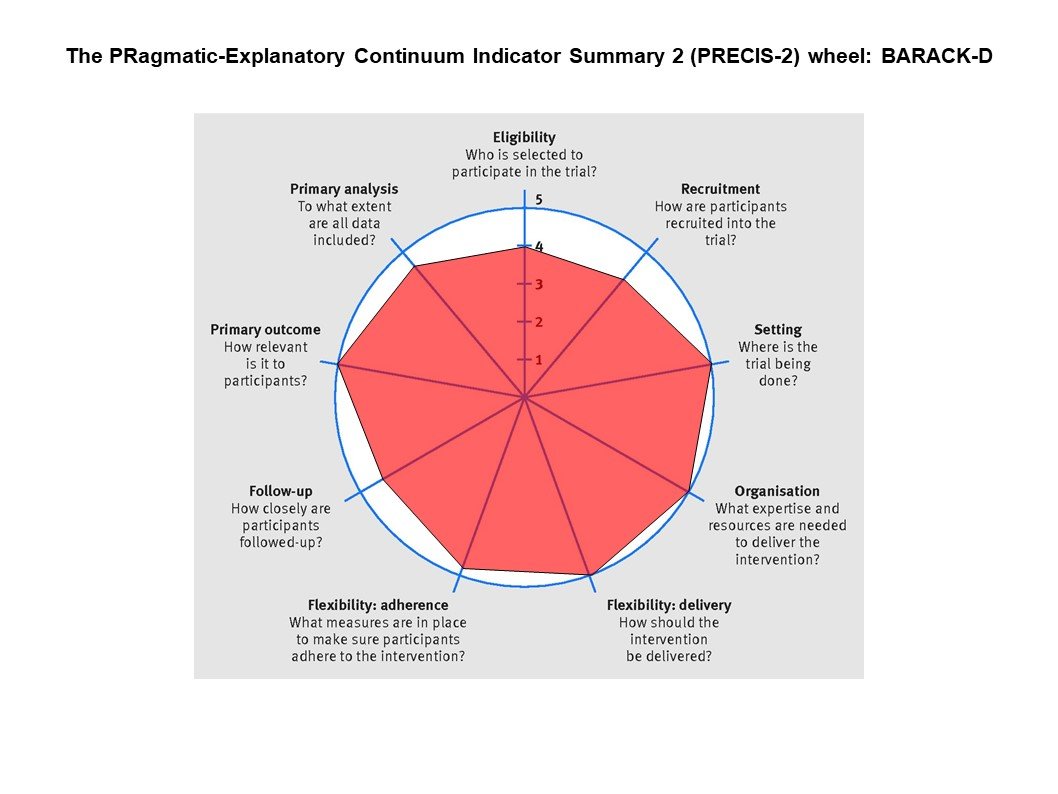

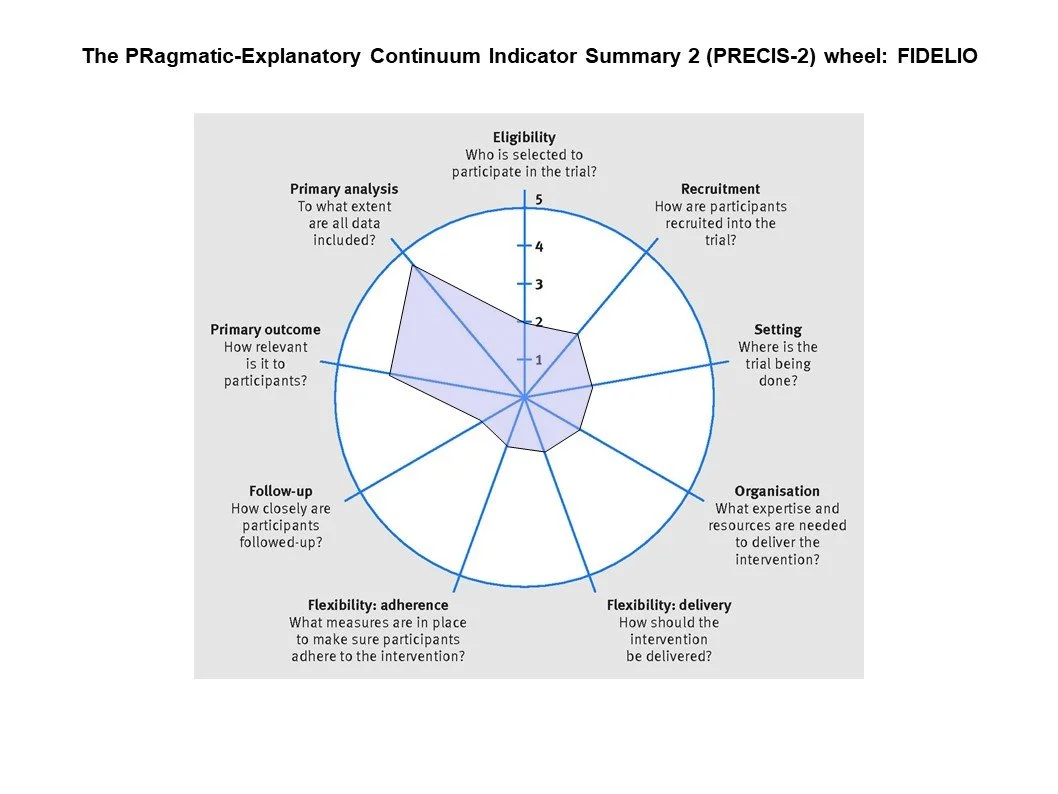

A brief segue into these two contrasting study designs is useful to understand why the FIDELIO/FIGARO results vary so much from BARACK-D, apart from the different molecules. See the #NephTrials blog from Manasi Bapat for more on the pragmatic trial study designs.

From the figures below, you can see that BARACK-D was very pragmatic - including a broad swathe of CKD patients recruited from general practice with a simple intervention, and follow up visits embedded into routine care. FIDELIO was quite different, with carefully chosen eligibility criteria making sure only patients at high risk of clinical outcomes but lower risk of adverse events, a run-in period to weed out participants at high risk of hyperkalemia, liberal use of K binders to maintain participants on finerenone. These aspects of FIDELIO can be considered ‘better’ at trying to show whether in the best possible scenario if finerenone has a benefit. But it does underscore that one does need to be careful in selecting patients who would benefit, excluding patients who might be harmed, and spending time and effort in keeping them on finerenone and keeping them safe. Finerenone is not a ‘fire and forget’ intervention, nor is spironolactone. Similarly, if the finerenone trials would not have been done, one might draw the (erroneous) conclusion that MRAs do not work at all in CKD. Thus both trial designs have their pros and cons - and in this setting, the explanatory trials clearly were the right choice (and one can see why Industry prefers them to pragmatic trials).

PRECIS-2 depiction of BARACK-D (left) and FIDELIO (right)

But what about FINEHEARTS?

This week’s #NephJC is on the FINEHEART analysis, a curious study which includes FIDELIO, FIGARO (both in diabetic CKD), and FINEARTS (not in diabetic CKD). Why would one do that? If you check, there has been carpet bombing of the cardiology journals with various flavors of analysis following FINEARTS HF. FINEARTS by age (Chimura et al Circ Heart Fail 2024), across EF (Docherty et al Circ 2024), time to benefit (Vaduganathan et al JACC 2024), with or without flozins (Vaduganathan et al Circ 2024), estimated long term benefit (Vaduganathan et al JAMA Cardiol 2024), the generalizability of kidney risk (Ostrominsky et al J Card Fail 2024). In all this profusion of publications, let’s not lose sight of the fact that in FINEARTS HF, there was no renal benefit at all. In HFpEF, if you want to use finerenone, use it to prevent HF hospitalization, not for the kidneys. And from a practical point of view, spironolactone also works as well (from the TOPCAT geographic analysis Pfeffer et al Circ 2014). This also represents the contrast between investigator initiated and governmental agency funded trials (TOPCAT, SPIREN, BARACK-D) in which the eligibility/enrolment were messed up or not achieved, interventions were completely missed or dropped out early, and possibly many other gaps and slips. These are poorly funded trials done by academic investigators with barebones infrastructure - and consequently have these ‘flaws’ with a resulting paltry publications. The tsunami of finerenone papers within a month of the trial’s meticulous completion demonstrates the power of money and logistical capabilities.

Pfeffer et al Circ 2014

What about the other ns-MRAs?

(update Oct 21st 2024).

Indeed there are other non-steroidal MRAs - finerenone is not the only one. Esaxerenone (previously CS-3150, marketed as Minnebro, coming in 1.25 to 5 mg strengths) has undergone trials in hypertension and has been approved for the same in Japan. Despite a phase 3 trial demonstrating albuminuria reduction (ESAX-DN, Ito et al, CJASN 2020) , we haven’t heard about its development further yet. Another one was ocedurenone (previously KBP-5074) which did undergo a phase 2 trial as well, in advanced CKD (stages 3b and 4; BLOCK CKD, Bakris et al Hypertension 2021) demonstrating BP lowering without hyperkalemia within the constrains of a small and short trial. It was bought by Novo Nordisk (of Ozempic aka Semaglutide fame) who started a large phase 3 trial (CLARION CKD) for hypertension in CKD, enrolling over 600 patients. Sadly it was terminated for futility after the 12 week follow up data came out (Novo Nordisk press release). Lastly there is balcinrenone (Astra Zeneca) which is not a classical MRA, but a mineralocorticoid receptor modulator. In in vitro studies it is a partial antagonist, but it demonstrates albuminuria lowering (Erlandsson et al BJCP 2018), though perhaps with mixed results (MIRACLE, Lam et al Eur J Heart Fail 2024). The MIRO-CKD (Phase 2b RCT; balcinrenone + dapagliflozin, N = 300 in proteinuric CKD) and BALANCED HF (phase 3 RCT; balcinrenone/dapagliflozin in HF = CKD, N = 4800) trials with this molecule are ongoing.

That still leaves the Aldosterone Synthase inhibitors though?

Indeed, we discussed one of the phase two trials a few months ago (Tuttle et al, Lancet 2024 | NephJC Summary). though one might think of these as ACEi (aldosterone synthase inhibitors or ASIs) versus ARBs (MRA), that comparison might not be perfect. ASIs might be more potent than MRAs at taking out the circulating aldosterone, which is something you may have run into if treating a really severe case of primary aldosteronism medically. These drugs, however, are not being developed for PA (a small market, though arguable point) but in hypertension and in diabetic nephropathy, with multiple companies and molecules in phase 3 development:

Baxdrostat (Astra Zeneca) in hypertension (Phase 2 RCT: Freeman et al, NEJM 2022; Phase 3 RCT: BaxHTN, N = 720), and in proteinuric kidney disease (ARCTIC, N = 2500 phase 3 RCT of baxdrostat + dapagliflozin)

Lorundrostat (Mineralys) in hypertension (Phase 2 RCT Laffin et al, JAMA 2023; phase RCT with N = 1000)

Vicardostat (previously known as BI 690517) in DM & non DM CKD (EASiKidney, phase 3 RCT, N = 11000 of vicardostat + empagliflozin)

Different mechanisms of MR antagonists and ASI. (Ando H, Hypertens Res,2023)

Conclusion

So where does this leave us hardcore spiro-stans? None of the large outcome trials of spironolactone have reported a benefit. Include the as-yet-unpublished ALCHEMIST trial of spironolactone in hemodialysis. ACHIEVE, like Obi-Wan Kenobi, is the last hope of the spironolactone fanatics - and with its run-in phase, and significant efforts to keep people on spironolactone. Though it has some pragmatic aspects (e.g. broad inclusion criteria, outcome ascertainment) it is tight enough to provide a clear answer of the potential benefit of MRAs in hemodialysis.

Commentary by Swapnil Hiremath