#NephJC Chat

Tuesday 9 pm Feb 6 EDT

Wednesday 9 pm Feb 7 IST

Kidney Int. 2024 Jan;105(1S):S1-S69. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2023.09.002.

KDIGO 2024 Clinical Practice Guideline for the management of LUPUS NEPHRITIS

Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Lupus Nephritis Work Group

PMID: 38182286

KDIGO Lupus Nephritis webpage

KDIGO 2024 CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF LUPUS NEPHRITIS

Lupus gets its Latin name from the word for “wolf”, and it has been used to describe the disease since the Middle Ages. Later, in the 18th century, it was poetically named by a French dermatologist “lupus érythémateux”, or Lupus Erythematosus, to describe the facial lesions that resembled a wolf’s bite (Felten R et al, J Am Acad Dermatol, 2022). More recently, Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) facial lesions have been likened to a butterfly. This might be more apropos for this discussion as we discuss the metamorphosis of care in the last few years due to new therapeutics in this challenging autoimmune juggernaut. So the question remains: when, where, and how do newer agents fit into the algorithm of lupus nephritis (LN) treatment? Let’s see if KDIGO can help us wolf down and digest all the new guidelines for treating LN.

Lupus Nephritis (LN) comes in many shapes, forms, and patterns. It is diagnosed by a kidney biopsy (gold standard) and is separated into six classes based on a classification system by the International Society of Nephrology and Renal Pathology Society (ISN/RPS). However, separating the microscopic findings into class I-VI alone is inadequate, and we rely on clinical characteristics like proteinuria and declining GFR to guide treatment strategies. Chronicity and activity scores on the diagnostic kidney biopsy are also helpful in determining prognosis and potential efficacy of immunosuppression. Activity on a biopsy ≥ 2 indicates a need for immunosuppression. Active lesions on kidney biopsy include endocapillary hypercellularity, neutrophils/karyorrhexis, fibrinoid necrosis, hyaline deposits, active crescents, and interstitial inflammation, as summarized in the table below. (Figure 2)

From: KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Lupus Nephritis, S24

KDIGO has guided nephrologists’ paths in many aspects of kidney disease: chronic kidney disease (CKD), anemia in CKD, acute kidney injury… Do you know what all these guidelines have in common? The eagerness of nephrologists across the world for updated guidance, as all these guidelines were published in 2012! Oddly, only 27 months after the glomerulonephritis guideline, KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Lupus Nephritis was published. The rush to update the guidelines may seem unusual, but ultimately, we will let you be the judge of its merits. Compared to KDIGO 2021 Glomerulonephritis guidelines (chapter 10), which had only 3 graded recommendations, 2024 has six! Before we get to the heart (and kidneys) of the topic, let’s remind how these guidelines are graded:

From: KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Lupus Nephritis, S7

Let’s start with lab testing and deciding when to biopsy a patient with lupus.

10.1.1 Diagnosis of LN

From: KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Lupus Nephritis, S15

No doubt, SLE and LN present in patients as many different levels of disease activity and severity. Hence, unlike most other GNs where the need for a repeat biopsy is uncommon after initial diagnosis, repeat biopsies in LN are often necessary to detect changes in class of LN as well as activity/chronicity. Active and frequent monitoring of kidney function and proteinuria is necessary to detect changes suggestive of a lupus flare. In this new guideline, we still rely heavily on daily proteinuria as the main indication for renal biopsy. (By the way, what was the primary outcome in BLISS-LN, wink-wink? See discussion below.) Although the above algorithm suggests “considering” a renal biopsy with > 500 mg/d of proteinuria the workgroup did recognize that this should be in the context of other markers of disease activity, to avoid unnecessary procedures. Ultimately, in 2024 we reiterate that it may not make sense to perform an invasive test without a compelling indication that would change treatment strategies. (Zickert A, et al, 2014 and Malvar A, et al, 2017) Notably, a low-evidence observational study showed that the histologic aspect had better flare predictive values than proteinuria, complement, and anti-dsDNA antibodies (Malvar A, et al, 2019).

Mentionable, according to figure 3, flozins aka SGLT2is are recommended as nephroprotective medications (Flozin like the Wolf), in patients with stable kidney function. A preliminary study of dapagliflozin in a small number of patients with SLE (18 with LN) found no difference in proteinuria following therapy (Wang H, et al, 2022). The EULAR SLE guideline also recommends flozins to patients with LN with reduced GFR below 60–90 mL/min or proteinuria more than 0.5–1 g/day, on top of ACE/ARBi during the maintenance phase (Fanouriakis A, et al, 2024).

The reported benefits of antimalarial use in SLE include decreasing flare rates, higher response rates to immunosuppression therapy, slower progression of kidney disease, lower incidence of cardiovascular and thrombotic events in patients with antiphospholipid antibodies, less organ damage, improved lipid profile, and better preservation of bone mass. The most feared side effect of hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) is retinal toxicity, which seems to be dose-dependent, with the highest risk at a dose of >5 mg/kg/day of absolute body weight (OR 5.67) (Melles RB et al, 2014). A recent observational study found the flare risk was 2-fold higher for HCQ doses of ≤5 mg/kg/day (Jorge AM et al, 2022). Patients at higher risk for retinal toxicity (kidney disease, preexisting macular or retinal disease, tamoxifen treatment), should be closely monitored by ophthalmologists, and use no more than 400mg/day HCQ (or 5 mg/kg/day). According to recently published EULAR lupus guidelines, in selected at-risk cases, monitoring HCQ serum levels may be helpful, but large-scale monitoring is impractical (Fanouriakis A, et al, 2024). Additionally, HCQ toxicity (hemolysis) is more common in patients with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency, hence, measurement of G6PD levels is preferred in patients of African, Asian, or Middle Eastern origin before starting.

The overall balance between benefits and potential risks provides the basis for recommending HCQ use as part of general management in patients with SLE. Hopefully, future pandemics won’t cause a run on antimalarials, limiting access to patients who desperately were seeking these therapeutics. As the saying goes: for the strength of the pack is the wolf, and the strength of the wolf is the pack (work together y’all).

10.2.2.1: Approach to immunosuppressive treatment for patients with class I/class II LN

Patients without proteinuria rarely have progressive disease and are not candidates for immunosuppression. In fact, for patients with low grade proteinuria and preserved renal function the use of immunosuppression should only be considered to treat systemic complications of SLE.

Patients with mesangial LN lacking proliferative glomerular lesions (ISN/RPS class I or II disease), rarely have progressive disease. These patients frequently have low grade proteinuria and/or microscopic hematuria, and may not require immunosuppressive therapy. However, a subset of patients with class I or II disease may have concurrent podocytopathy (lupus podocytopathy as seen on EM), which can be treated with corticosteroids, similar to minimal change disease. Patients with SLE and nephrotic syndrome are much more likely to have membranous nephropathy, so podocytopathies could be considered to be a sheep in wolf’s clothing (sigh, more bad wolf jokes).

This guideline is the most significant change in the treatment of LN, or better said this recommendation is the essence of this guideline's existence?

Dual immunosuppression with glucocorticoids and a second agent is now a standard of care for decreasing proteinuria and maintaining kidney function. Triple immunosuppressive therapy can also be considered in non-responders with the potential for increased serious adverse events and cost. Lower doses, of all medications but particularly steroids, are always preferred over higher doses in medication regimens as long as disease progression is kept in check.

IV cyclophosphamide can be considered in those who might have difficulty adhering to an oral regimen, given that all therapies other than belimumab are oral. Of note, cyclophosphamide has studies with long-term efficacy (that is lacking in the other agents) but has a concerning safety profile including such effects as infertility and potential malignancy with prolonged exposure. Most nephrologists with access to MPAA, generally prefer it over cyclophosphamide due to a much safer side-effect profile in patients with mild to moderate LN.

Without treatment, the prognosis for kidney survival in patients with class III/IV LN is poor. The choice of initial treatment for class III/IV LN entails personalized consideration of the balance between benefit and risk and is informed by data on short-term response and long-term efficacy and safety, potential adverse effects, including infections and cumulative toxicities, quality of life, and factors relevant to patient experience and adherence. In addition, physician experience and comfort with prescribing may influence immunosuppressive choice.

Voclosporin

The calcineurin inhibitor (CNI) voclosporin (from the AURORA trials) deserves additional consideration as part of this guideline. AURORA 1 was a multinational phase 3 trial in patients with eGFR > 45 ml/min/1.72m2. (Rovin BH et al, 2021) Proteinuria decreased at 1 year compared with placebo (OR 2.65, 95% CI, 1.64-4.27). Patients who completed AURORA 1 were then eligible to move on to AURORA 2, an additional 2 years of blinded therapy versus placebo. (Saxena A, et al, 2024) AURORA 2 showed sustained reduction of proteinuria with voclosporin (similar to other CNIs), with no concerning safety signals. Unfortunately, over the 3 years total, there was no significant improvement in eGFR slope over placebo. Finally, as pointed out in the NephJC discussion of AURORA, practitioners should consider whether the change in a single amino acid in voclosporin from the structure of cyclosporin is worth the cost. Some may point to the lack of need for monitoring of levels and subsequent dosage adjustment as a potential cost savings for voclosporin, but this hardly balances with the cost difference of the medication itself. Voclosporin has yet to elevate itself over other CNIs and it is not specifically recommended ahead of tacrolimus by these guidelines.

Belimumab

It is interesting to see belimumab as a first line treatment for class III/IV LN, even if as a conditional recommendation. Most clinicians have had much more experience with MMF/ cyclophosphamide/ CNIs, and are familiar with dosing and common side effects of these medications. Also, belimumab (similar to voclosporin) has a significant associated cost, as compared with other first-line agents which may limit its use. B-cell–activating factor (BAFF, also known as B lymphocyte stimulator or BLyS) is a cytokine expressed in cells with B-cell lineage. Belimumab, a human monoclonal antibody that inhibits BAFF, was approved by the FDA for the treatment of SLE in 2011 in both IV and SQ formulations. In BLISS-LN, patients treated with belimumab had superior primary efficacy renal response rate (PERR, a composite endpoint with proteinuria ≤0.7 g/g [70 mg/mmol]), compared to placebo in patients receiving standard dual immunosuppression (Furie R, et al, NEJM 2020). However, the shadows of the past NephJC discussions still haunt us. We clearly remember that for the primary outcome, the proteinuria threshold was changed mid-game from 0.5 to 0.7 grams/day. Unfortunately, if we examine what if the primary outcome would’ve been had the proteinuria limit stayed as initially proposed…BLISS-LN would have been a negative trial. Only a fool follows the herd of sheep to the pack of wolves.

Table S2 from Furie R et al NEJM 2020

A secondary analysis showed the overall increase in PERR and complete response rate (CRR) when belimumab was added to standard therapy was attributed to patients with a proliferative histologic component, while there was no observed treatment difference associated with belimumab in patients with class V LN (PERR: OR 0.65; 95% CI: 0.23–1.86; CRR: OR 0.83; 95% CI: 0.27–2.62). (Rovin BV, et al, 2022) Even if BLISS-LN was not convincing, patients treated with the belimumab-containing triple immunosuppressive regimen had lower rates of adverse kidney outcomes. Moreover, an analysis of 5 phase 3 RCTs (low dose belimumab as add-on to standard of care vs placebo) showed belimumab appeared protective against renal flares in nephritis-naïve patients with SLE. (Parodis I, et al, KIreports, 2023)

In an economic analysis of these two newer agents, the authors attempted to determine cost-effectiveness by probabilistic analysis, including different levels of disease activity. (Mandrik O et al, CJASN 2022) The incremental cost-effectiveness results were approximately $95,000 and $150,000 per quality-adjusted life years for belimumab and voclosporin, respectively, each compared with the standard of care. The study concluded that belimumab, but not voclosporin, met the “willingness-to-pay” threshold of $100,000 per quality-adjusted life year. As nephrologists gain experience with these newer agents for LN, additional data will be generated to inform a more refined cost-effectiveness analysis.

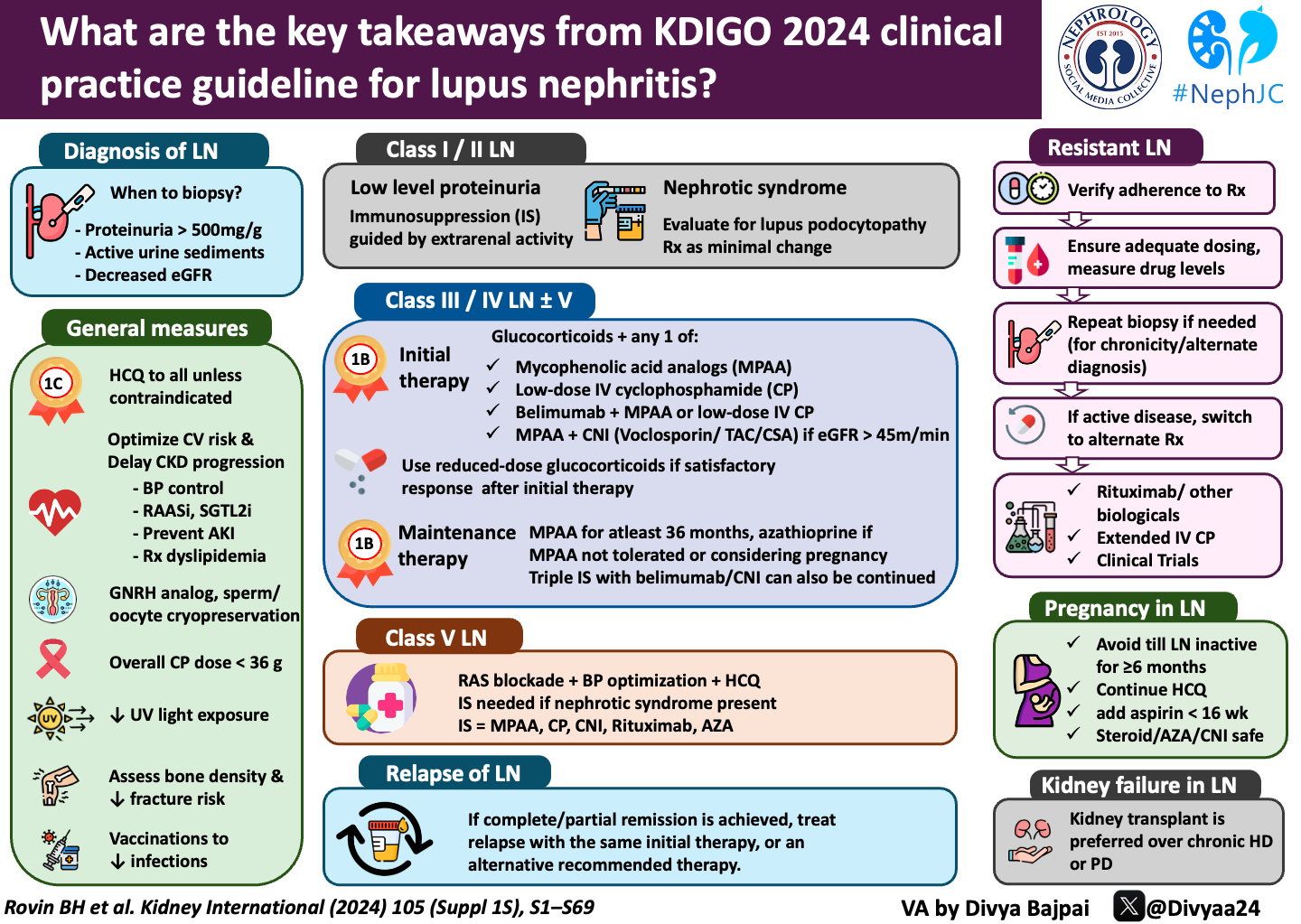

Adapted from Executive summary of the KDIGO 2024 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Lupus Nephritis

Finally, azathioprine and leflunomide can be considered as alternative first line drugs. Patient intolerance, lack of availability, wish to become pregnant, and/or excessive cost of standard drugs may have a role in treatment choices. These treatments may be associated with inferior efficacy, including increased rate of disease flares and/or increased incidence of drug toxicities.

Recommended treatment options for active LN are summarized in the flowchart below:

From: KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Lupus Nephritis, S30

No improvement, or worsening despite treatment of LN for 3–4 weeks, is unsatisfactory and warrants assessment of potential causes for nonresponse, whereas patients who show response to treatment can be closely monitored and investigated when the level of improvement after 3–4 months of therapy is suboptimal. A 2-month timeframe to see improvement was suggested based on the ALMS trial, but deterioration needs to be evaluated on an individual basis. (Sinclair A, et al, 2017) KDIGO also suggested additional evaluation if patients were unresponsive to treatment:

High-intensity immunosuppression for the initial treatment of LN is recommended for 3–6 months, depending on the regimen. At the end of initial therapy, only about 10%–40% of patients achieve complete response (depending on the definition of “remission” of which there are many), and relapses are frequently encountered. Azathioprine, CNIs, belimumab, mizoribine, or leflunomide can be considered as potential alternative therapies after MPAA. Maintenance immunosuppression should be continued ≥36 months for most patients with a proliferative GN (class III/IV). As of now, there are no long-acting agents for maintenance, and it can be unclear when it is safe to stop therapy; this is an unmet need in SLE. MPAA and azathioprine were directly compared as maintenance agents in 2 major clinical trials. In the maintenance phase of the ALMS study, it was shown that over 3 years of follow-up, the composite treatment failure endpoint of death, kidney failure, LN flare, sustained doubling of SCr, or requirement for rescue therapy was observed in 16% of MMF-treated patients and in 32% of azathioprine-treated patients (Sinclair A, et al, 2017). In contrast, the Mycophenolate Mofetil Versus Azathioprine for Maintenance Therapy of Lupus Nephritis (MAINTAIN) trial showed no difference in time to kidney flare between the 2 groups, with a cumulative kidney flare rate of around 20% in both groups after 36 months (Tamirau F, et al 2016). Finally, steroids should be tapered to the lowest possible dose that controls LN and systemic manifestations. Further guidance on steroid-sparing immunosuppressive management is included in the flowchart below.

From: KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Lupus Nephritis, S39

10.2.4.1: A suggested approach to the management of patients with pure class V LN

Class V LN (membranous lupus nephritis) accounts for 5%–10% of all LN cases. Data on clinical management are based on very few RCTs with small sample sizes, analyses of pooled data, and observational studies. Long-term follow-up data show that 10%–30% of patients with class V LN progress to kidney failure and the risk of progressive CKD is associated with the severity of proteinuria.

From: KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Lupus Nephritis, S44

10.2.5.3.1: After a complete or partial remission has been achieved, LN relapse should be treated with the same initial therapy used to achieve the original response, or an alternative recommended therapy.

There is no data that focuses on the treatment of LN flares as a separate disease entity from LN. However, it is generally agreed that there is no major difference between management of an LN flare and that of de novo active LN. Some special considerations during a relapse include cumulative cyclophosphamide exposure, pregnancy status, tolerance of previous regimens and more aggressive disease activity markers. At the first signs of increased activity (low C3/C4, worsening proteinuria) empiric escalation of maintenance medications as well as steroids may be warranted. Finally, impending LN flares may be preventable, at least for some patients, but large studies of sufficient duration are needed before this approach can be truly embraced.

10.3.1.1: Patients with LN and thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) should be managed according to the underlying etiology of TMA.

TMA is a pathologic description of vascular endothelial injury secondary to various etiologies. It often occurs concurrently with another form of LN (generally class III/IV disease). The key to a good outcome for TMA in LN is rapid diagnosis and prompt treatment. Workup for suspected TMA is included in the flowchart alone.

From: KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Lupus Nephritis, S48

10.3.2 Pregnancy in patients with lupus nephritis

Patients should attempt to avoid pregnancy until >6 months remission.

Hydroxychloroquine and low-dose aspirin (< 16 weeks gestation) can be used to decrease complications during pregnancy. Use of hydroxychloroquine has been associated with decreased SLE activity during pregnancy. Glucocorticoids, hydroxychloroquine, azathioprine, tacrolimus, and cyclosporine are considered “safe” immunosuppressive treatments during pregnancy. There is currently limited evidence for the newer agents (belimumab and voclosporin). Animal studies did not show additional birth defects with belimumab In humans, the evidence is conflicting. Two case series did not find an increased pattern of birth defects. (Kao JH, et al 2021 Ghalandari N, et al, 2023) In another cohort, with only 55 patients recruited, 10 out of 53 live births had major birth defects. (Juliao P, et al, 2023) Voclosporin formulation contains alcohol, and the current recommendation is that voclosporin should be avoided in pregnant and lactating patients. (Shah VR, 2023)

How about conflicts of interest?

Before concluding, we’d like to come full circle and respond, even if only partial to the question: why were two guidelines published in only 27 months? Examining the bibliographic and disclosure information: 5 of the authors received funds from GlaxoSmithKline (GSK being the pharma company behind belimumab) and 2 of the authors received funds from Aurinia- voclosporin producer (1 of the authors being part of the company’s board). However, if you live with wolves you have to act like a wolf, and these guidelines might be an integral step for public stakeholders to introduce newer drugs, and get insurance coverage. From a universal healthcare system point of view, new guidelines can be leveraged to negotiate more affordable prices, having the argument that 2 guidelines recommend belimumab in treatment of proliferative LN (EULAR, Fanouriakis A, et al, 2024).

Conclusion

There are several additional therapeutics currently being evaluated for the treatment of LN. These novel drugs are in phase 2 and 3 trials. When these trials are completed, hopefully with some success, the KDIGO guideline will be updated again to provide the nephrology community with timely evidence-based recommendations for the management of LN. Although this new guideline is not significantly altered from previous strategies in treating class II/IV LN, we can all appreciate that need for a more rapid turnover of recommendations given the swift evolution of new treatments. Be glad you’re not a lone wolf in this LN landscape.

Fig. 2. Targeted therapies according to their mechanisms of action, phases of development, and status from Felten R et al, 2023