#NephJC Chat

Tuesday Oct 10th 9 pm Eastern

Wednesday Oct 11th 8 pm BST, 12 noon Pacific

JAMA. 2017 Oct 3;318(13):1233-1240. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.10913.

Effect of an Early Resuscitation Protocol on In-hospital Mortality Among Adults With Sepsis and Hypotension: A Randomized Clinical Trial.

Andrews B, Semler MW, Muchemwa L, Kelly P, Lakhi S, Heimburger DC, Mabula C, Bwalya M, Bernard GR.

PMID: 28973227 Full Text at JAMA

Introduction

This study on sepsis and resuscitation comes from Zambia, a country with only 10 ICU beds. The scientific ambition to run this trial must be respected. Science is about asking questions and deploying the available resources to find the answer. Andrews and team should be commended for making it happen in a resource constrained country.

The Question

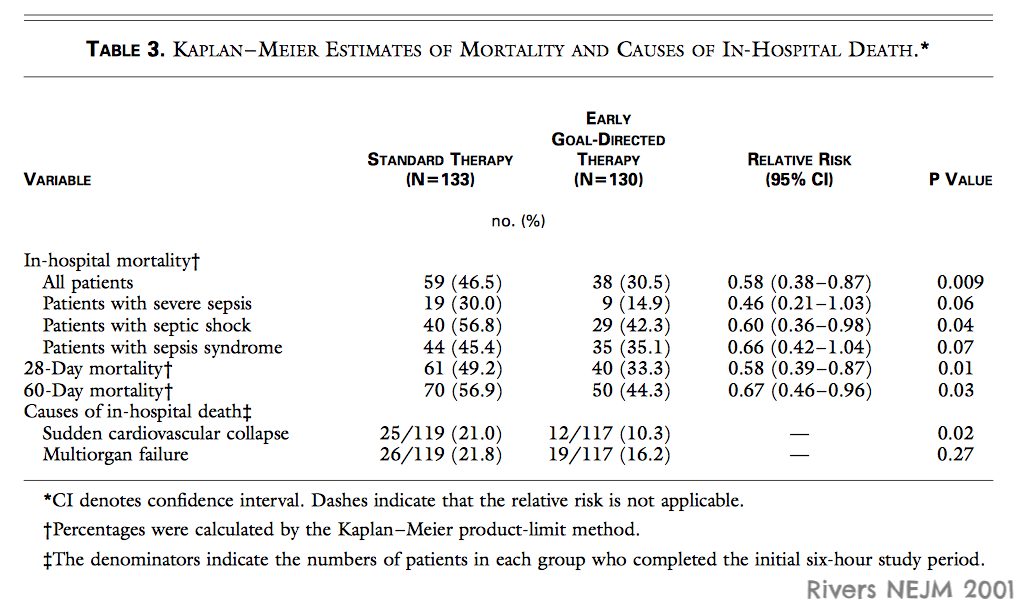

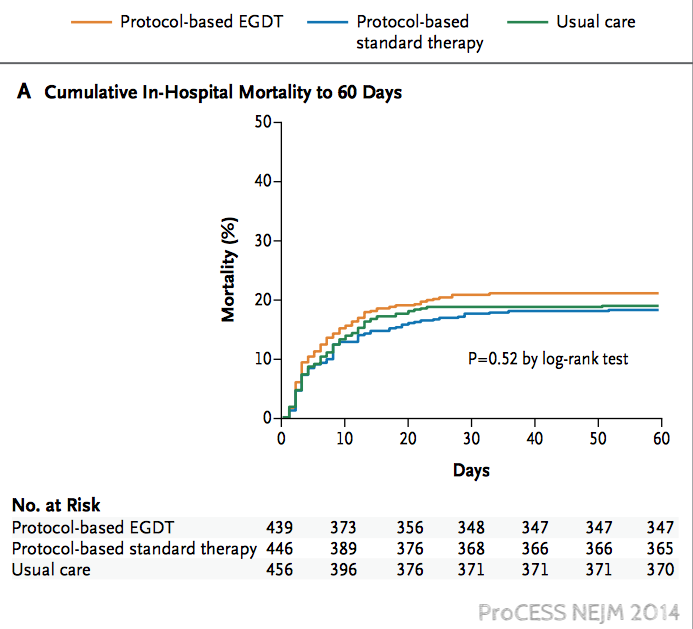

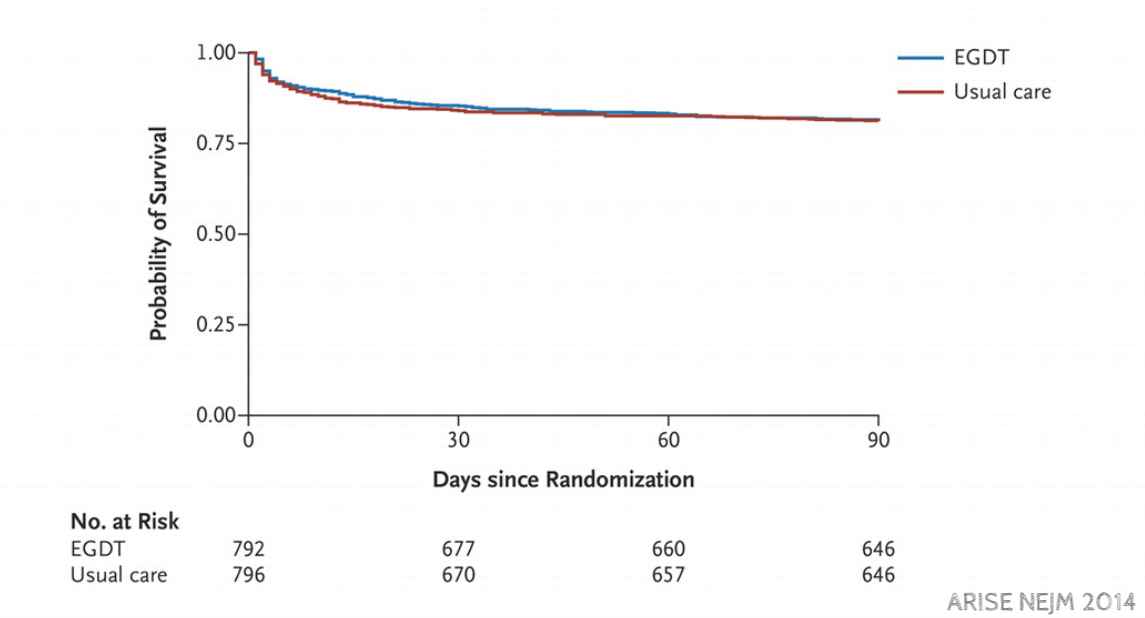

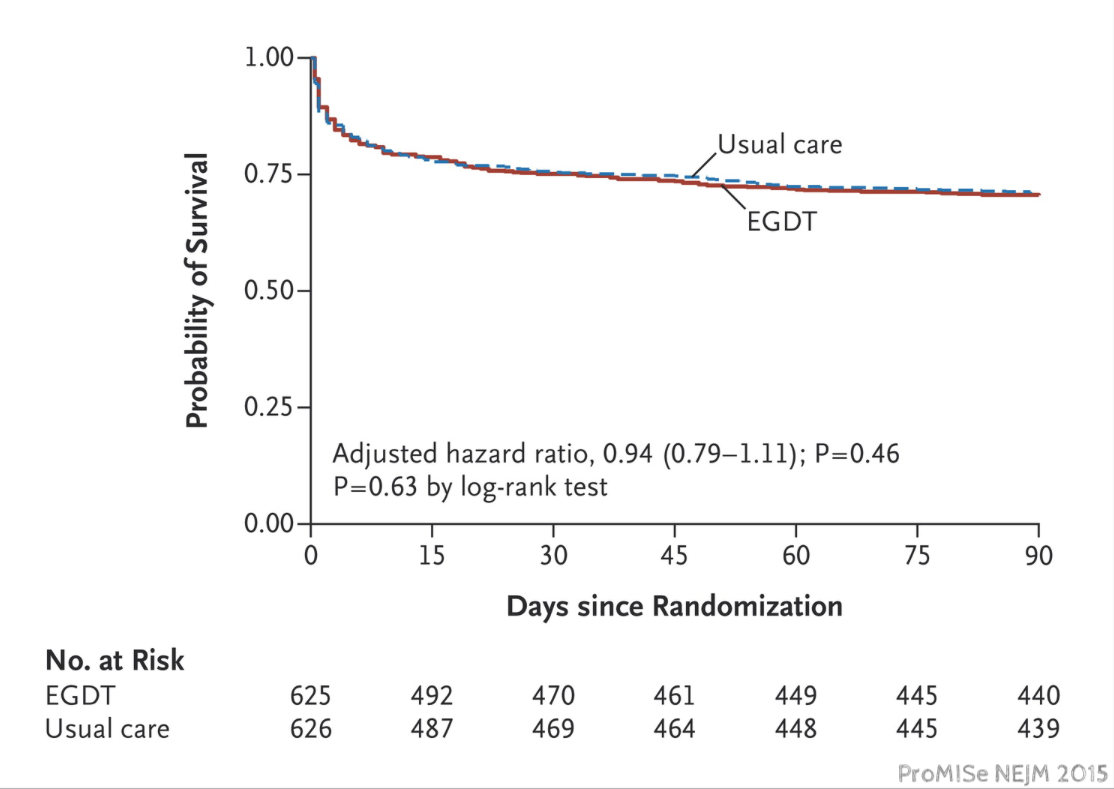

Sepsis is most common in developing countries but just about everything we know about sepsis comes from wealthy countries. Andrews asked whether the lessons of early goal directed therapy could be implemented in Zambia. Andrews was not alone in wanting to know if protocols for sepsis worked as well as Rivers had shown in 2001. In 2014, just a few months after Andrews finished collecting data in Zambia, the ProCESS trial was published which was unable to reproduce Rivers' findings. This was followed by similar findings in ARISE in October of 2014 and ProMISe in 2015.

After repeated demonstrations of futility anyone would be skeptical if Andrews and team showed a benefit, but the resource limitations of working in Zambia, could hobble standard care enough to let a sepsis protocol save lives.

Methods

The study is an open-label randomized clinical trial of a specific sepsis protocol, the authors named The Simplified Severe Sepsis Protocol (SSSP), compared to usual care.

The SSSP consisted of two fluid bolus, the first two liters bolus was over an hour and the second two liter bolus was over 4 hours. Patients were given dopamine for low blood pressures and transfusions for hemoglobins below seven.

A total of 209 patients--mostly HIV positive--presenting with suspected infection, at least 2 systemic inflammatory response syndrome criteria, and hypotension were randomized to either standard care or the simplified severe sepsis protocol (SSSP)

SSSP group (106 patients)

Standard care group (103 patients): Treating physicians established intravenous fluid administration, vasopressor use, and blood transfusion. The volume of intravenous fluid administered in the first 6 hours averaged less than 2-liters and 40% didn’t receive any intravenous fluid bolus. Vasopressors were used in less than 2% of standard care patients.

Results

The primary outcome was in-hospital mortality:

SSSP group: 48% (51 deaths)

Standard care group 33% (34 deaths)

Number Needed to Harm: 6.6 (95% CI 3.5-50 – based on the limits expressed in the absolute difference).

Secondary outcome of 28-day mortality was similar:

SSSP group: 67%

Standard care group 45%

Anyway you cut it the SSSP kills:

This is not your typical sepsis cohort:

Almost 90% were HIV positive with a median CD4 below 100

Half of the positive culture results were tuberculosis (TB)

Mean hemoglobin was 7.8 g/dL

Median albumin level was 2.2 g/dL

Patients randomized to the SSSP group received far more fluids, a median of 3.5 liters (IQR, 2.7-4.0 L) of IV fluids compared with 2.0 liters (IQR, 1.0-2.5 L) in the standard care group. Only 48% of usual care patients received any bolus at all.

Limitations

This study highlights that guidelines need to be context specific. What works in New York, may not fly in Lusaka.

The results are also aligned with Uganda’s FEAST trial by showing benefit of a restricted fluid resuscitation approach in kids with sepsis (Video Link)

The precise mechanisms explaining this results are uncertain. The study population - young, malnourished at risk for TB and malaria - was predominantly prone to pulmonary edema or reperfusion injury from the speed or amount of volume expansion, also this population seemed seriously ill when arriving to a medical ward.

IV fluids are a drug and like any medication they can be helpful or hurtful depending on dose. Especially in Zambia, too much fluid is bad because they don't have rescue resources (ventilators, dialysis, nursing care, etc). Only one patient in the entire study was cared for in the ICU.

Another lesson from the study is that JVP can´t be used as an end point for fluid administration. Here is an old discussion on the RFN blog. JVP is a window to the pressure in the right atrium (not volume) and it’s only part of a patient’s evaluation.

Being unblinded at a single centre, allows many “uncontrolled” interventions by the study staff that could have an impact between the study groups.

Dopamine use, as a first choice vasopressor should be questioned in view of its potentially deleterious side effects (impairing the ventilatory drive response to hypoxemia and hypercapnia and reducing arterial oxygen saturation through a regional ventilation/perfusion mismatching, higher risk of arrhythmias) and the increased rate of mortality associated with its administration in septic patients (there are already observational and interventional studies, here's a blog post on RebelEM).

Summary

In a cohort of Zambians with sepsis, a protocol driven resuscitation increased, rather than decreased (NNH of 6.6) hospital mortality.

Summary by Omar Taco, @errantnephron,

Nephrologist and #NSMC intern, class of 2017, Barcelona