Should we call 2024 the Renaissance of nephrology? It was probably the richest year in RCTs in the nephrology world, reflected in the higher number of Late-Breaking Clinical Trials sessions at every big nephrology congress. Compared to 2023, you will see some topics recurring, like IgA nephropathy, xenotransplantation, and hyponatremia correction speed. Even if it didn’t make it to the top 10, another mentionable topic is NephTwitter migration to BlueSky starting Nov 2024.

FLOW: GLP-1 RAs in CKD

Once upon of time was Gila Monster, a metabolic multitasker, which helped humankind discover GLP-1 (see NephMadness blog). It started in the ‘80s, then fast forward 40 years later, GLP1 receptor agonists became one of the main drug classes in type 2 DM and obesity treatment, reducing MACE (Sattar et al, Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021), and strokes (SUSTAIN-6 Marso et al, NEJM 2016, REWIND Gerstein et al, Lancet 2019). The same promising effects on MACE were shown in the absence of DM, in patients with heart failure and obesity (SELECT trial, Lincoff et al, NEJM 2023, Deanfield et al, Lancet 2024).

What about GLP1-RA and the kidneys?

Despite flozins, RASi, and non-steroidal MRAs improving kidney and CV outcomes in CKD, there is still a high residual risk and unmet needs to be addressed.

Slide from Peter Rossing’s presentation- Current treatment strategies, unmet medical need, FLOW rationale, during FLOW session, 61st European Renal Association Congress

Analysis of previous trials (ones without primary kidney outcomes 😳)repeatedly showed reduction of proteinuria and signals of progression of CKD.

Figure from Rossing et al NDT 2023

The FLOW trial (Perkovic et al, NEJM 2024) was a phase 3 randomized trial, of 3,533 patients with type 2 diabetes and CKD (eGFR 50-75ml/min or 25-50 ml/min with albuminuria) who received 1 mg of subcutaneous semaglutide weekly, or placebo. Over a median follow-up of 3.4 years, semaglutide reduced the risk of the primary composite outcome by 24% (HR 0.76, CI 95% 0.66-0.88). It also lowered the risk of kidney-specific outcomes (HR 0.79, CI 95% 0.66-0.94), cardiovascular death (HR 0.71, 95% CI 0.56 to 0.89), MACE (HR 0.82, CI 95% 0.67- 0.95), and death from any cause. (NephJC summary | Freely Filtered episode)

Few questions remain to be answered. First, the mechanism by which GLP1-RA protects kidney function remains uncertain. In the FLOW trial, semaglutide reduced the eGFR decline by 1.16 ml/min/1.73 m2 per year without the initial eGFR dip seen with RASi and flozins. indicating a distinctive renoprotective pattern. It also lowered the urinary albumin-to creatinine ratio, suggesting a direct effect on glomerular function. While weight loss and improved HbA1c were noticed, these don’t fully explain kidney benefits. The efficacy across BMI subgroups and potential higher doses or use in advanced DKD need to be further studied. Secondly, do GLP1-RAs work in non-DM CKD? The SELECT trial (Lincoff et al, NEJM 2023) showed promising results with semaglutide 2.4 mg reducing the composite kidney outcome risk and slowed eGFR decline by 0.75 ml/min/1.73m2 over 104 weeks. However, only 11% of the patients had an eGFR <60 and there was significant weight loss (-9.39%) in the semaglutide group. Moreover, a recent meta-analysis, including FLOW and SELECT trials showed sustained beneficial effects of GLP1-RA, irrespective of diabetes status. (Badve et al, Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol, 2025) Thirdly, GLP1-RAs might not have uniform class effects, given the variation of weight loss potency among agents.

Glipinate!

2. The Renaissance of IgAN: IgAN treatment trials

IgAN, one of the most prevalent and enigmatic glomerular diseases, has long resisted therapeutic advances. However, 2023 marked a turning point with the FDA approval of targeted-release budesonide based on the findings of the NefIgArd trial (NephJC summary) and results from sparsentan in PROTECT, set the stage for a new wave of groundbreaking clinical advances in 2024.

Complement inhibition emerged as a central strategy in halting IgAN inflammation. The APPLAUSE-IgAN (NEJM 2024) showed that iptacopan, factor B complement inhibitor, achieved a massive 38% reduction in proteinuria after 9 months in patients at high risk of progression. Similarly, the SANCTUARY trial (JASN 2024), showed that ravulizumab, a second-generation C5 inhibitor, reduced proteinuria by 40.4% while maintaining a favorable safety profile. Cemdisiran, an RNA interference therapy targeting C5, showed reduction in UPCR while stabilizing eGFR. Adding to this standout moment, IONIS-FB-LRx, an antisense oligonucleotide targeting complement factor B, delivered significant proteinuria reductions in Phase 2 trials and advanced to a global phase 3 trial in IMAGINATION.

Parallel breakthroughs included SC0062 (JASN 2024), a selective endothelin receptor A antagonist, which significantly reduced proteinuria over 12 weeks with less peripheral edema incidents. The ALIGN trial (NEJM 2024) solidified the efficacy of atrasentan, with a 38.1% reduction in UPCR and a favorable safety profile. In addition, phase 2b atacicept demonstrated sustained reductions in biomarkers like Gd-IgA1 (-66%), hematuria (-75%), and UPCR (-52%), with a loss of only 0.6 mL/min/1.73 m² of eGFR over 96 weeks.

RNA therapies and monoclonal antibodies seek to reduce the pathogenic IgA. Sibeprenlimab, an anti-APRIL antibody, achieved significant 24-hour proteinuria reductions at 9 months in the VISIONARY Phase 3 trial, while povetacicept, a dual BAFF/APRIL inhibitor, demonstrated in RUBY-3 a 53.5% reduction in proteinuria. Meanwhile, exploratory therapies like CAR-T cell therapy and zigakibart continue to push the boundaries of immune modulation, targeting Gd-IgA1 and immune complexes to alter disease progression.

As these therapies advance, the integration of complement inhibitors, monoclonal antibodies, and RNA-based treatments is redefining IgAN treatment. The exploration of combination regimens incorporating complement inhibition, RAAS blockade, and SGLT2 inhibitors, alongside ongoing trials like NefXtend, focus on tackling IgAN's complex pathogenesis. The ultimate goal remains clear: preserve kidney function and improve patient outcomes. Stay tuned for 2025 an IgAN evolution.

3. Hypertension control trials (ESPRIT, BPROAD)

In medicine, so goes the maxim, if the number is too high, we should lower it. On the other extreme is John Hays’ quote “There is some truth in the saying that the greatest danger to a man with high blood pressure lies in its discovery, because then some fool is certain to try and reduce it.” The therapeutic ‘less is more’ nihilism led to the JNC 2014 decision to increase the target of blood pressure reduction to 140/90. There are persuasive biological arguments to be made for aiming high or aiming low. High blood pressure is associated with all sorts of badness including heart disease (particularly heart failure) and stroke. Lowering blood pressure too much can result in falls, syncope, and depending on the actual drugs used, a bunch of dyselectrolytemia (not to forget the dreaded hypercreatininemia). The impasse can be broken with empiric data, from randomized controlled trials (RCTs), and it was with SPRINT (Wright et al NEJM 2014 | NephJC Summary) in late 2014. However, rather than being embraced - it was one of the most divisive trials in this field. Naysayers critiqued the BP lowering method, the algorithm, the supposed harms of lowering BP, the early stoppage of the trial - any and all excuses to justify their underlying therapeutic nihilism. Is one trial sufficient to change clinical practice (notwithstanding the BP trialists collaboration which supported intensive BP lowering; Ettehad et al Lancet 2016)? But who else was going to do these costly and cumbersome RCTs of several thousand participants and costing several million dollars?

As Charles de Gaulle is supposed to have said, 'China is a big country, inhabited by many Chinese.' - and also many hypertension trialists it seems. In quick succession, the year has seen publication of a couple of really well done RCTs that justify intensive BP lowering. The ESPRIT trial (Liu et al, NEJM 2024 |NephJC Summary) reported a very similar reduction in major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) with intensive BP as SPRINT, but included ~ 38% of patients with diabetes in the trial population (unlike SPRINT which excluded DM). The BPROAD trial (Bi et al, NEJM 2024 | NephJC Summary) included only participants with DM, and reported an effect size very similar to the ACCORD BP trial at just over 20% RR reduction in MACE. There are several minor differences to glean, which you can wade through in our detailed NephJC summaries, but the big picture is that these two trials combined randomized 24,076 participants to intensive BP lowering targets, and unequivocally demonstrate a benefit of intensive BP lowering. Kudos to these trialists and their funders for making these RCTs happen. The dust has settled. The time to make excuses is done. We don’t need more research. Roll up your sleeves, and prescribe that chlorthalidone (or, ahem, some hydrochlorothiazide).

4. KDIGO CKD Guidelines

The past decade in nephrology has been a wild ride, full of exhilarating highs, like the success of flozins, and crushing lows with the pleiad of nihilistically negative trials. Despite all this turmoil, CKD guidelines have been stuck in time, rooted in 2012, when nearly two-thirds (43/69) of recommendations were graded “1” based on a scant collection of less than 20-30 trials. (KDIGO CKD Work Group, Kidney Int Suppl. 2013). Meanwhile, CKD silently grips 1 in 10 people worldwide, and by 2040,it’s set to become the 5th leading cause of death- a fate more dire than some cancers.

The 2024 KDIGO CKD guidelines were dissected by NephJC in 2 parts (CKD KDIGO part 1 and part 2), and drafted during Freely FIltered episode and it reflects the multitude of improving quality evidence in the last decade. Organized into 6 chapters, it comprehensively covers CKD diagnosis, risk evaluation, delaying CKD progression, CKD management, models of care, and research recommendations. Compared to 2013, the number of graded recommendations has been trimmed to 28, with 16x Level 1 (4- 1A, 6- 1B, 4-1C, 2- 1D) and 12 level 2 (2- 2A, 2- 2B, 5- 2C, 3 -2D), while many transitioned to practice points underscoring the nuanced gaps in evidence. (KDIGO CKD Work Group, Kidney Int, 2024)

Before 2005, nephrology lacked a universal CKD definition, relying heavily on expert opinion. The 2005 CKD staging (Levey et al. Kidney Int, 2005) introduced structure, while Kdigo now refined classification using CGR (Cause, GFR, ACR) approach. Despite of its many imperfections, creatinine-based eGFR remains the standard; combined cystatin-creatinine eGFR is suggested for precise clinical decisions, though cost and accessibility limitations persists and cystatin confounders exist (HF, high steroid doses, inflammation). Future debates should focus on refining eGFR equations and CKD diagnosis in specific populations.

Is precise CKD risk prediction possible?

Chapter 2 delivers a resounding “yes” with a singular class 1A recommendation: the imperative to predict kidney failure when navigating the CKD treacherous waters. The KFRE (Tangri et al, JAMA 2011), Veterans Affairs model, and Z6 Score (Zacharias et al, Am J Kidney Dis 2022) are proposed to tailor multidisciplinary interventions. Given that cardio-vascular comorbidities and mortality are higher in population with CKD, more precise CV risk prediction models are recommended: QRISK3 (Hippisley-Cox et al BMJ 2017), ckdpc.org (Chronic Kidney Disease Prognosis Consortium KI 2018) and the American Heart Association Predicting Risk of CVD EVENTs (PREVENT) (Khan et al Circulation 2024). Following the guideline’s release, two notable risk scores emerged. First, KDPredict (Liu et al BMJ 2024;) integrates mortality alongside kidney failure. The second one, Klinrisk, a machine learning-driven model, validated in populations from the CANVAS and CREDENCE trials, offers improved accuracy. It outperforms KDIGO heatmaps and the refitted four-variable KFRE at 3 years. (Tangri et al, Diabetes Obes Metab. 2024)

Slowing CKD progression: where we stand and quo vadis?

Chapter 3 is the most dense, including recommendations on delaying CKD progression and complication management.

There is no surprise, flozins were graded 1A for patients with CKD and diabetes with an eGFR ≥ 20ml/min/1.73 m2, and for patients with CKD, and a ≥20ml/min/1.73 m2 with ACR ≥200mg/g (20 mg/mmol) or heart failure (irrespective of the proteinuria level). Irrespective of DM status, at eGFR 20 to 45 ml/min/ 1.73 m2 with urine ACR <200mg/g, the flozins are graded 1B; the recommendation is sustained by the EMPAKIDNEY trial, which included a subgroup of patients without albuminuria. Flozins are recommended to be initiated at eGFR over 20 ml/min, which can be continued if eGFR declines further. However, DAPA-advKD results presented during Kidney Week showed a slower decline in eGFR with 1.21 ml/min/1.73 m2/year dapagliflozin, and a reduction in combined cardiorenal composite outcomes. This randomized controlled trial included a population with CKD stage 4 and 5, and a median eGFR of 18.9 ml/min//1.73 m2 and median UACR ~700 mg/g (tweetorial by S. Hiremath).

Non-steroidal MRAs are recommended if residual albuminuria on maximum RASi tolerated dose, or it’s considered to add any cardiovascular benefits. In FIDELIO-DKD (Bakris et al, NEJM 2020, NephJC summary), FIGARO-DKD (Pitt et al, NEJM 2021) trials and their pooled analysis FIDELITY (Agarwal et al, EHJ 2022), finerenone slowed CKD and decreased CV events in patients with advanced CKD and proteinuria. The recommendation was graded only 2A, “A” reflecting the high quality of the evidence behind- but would coming studies change the grading in the next version of the guideline? FINEHEART (Vaduganathan et al. Nat Med. 2024), the pooled analysis of the two aforementioned trials and FiNEARTS-HF consolidated the evidence of finerenone across cardio-reno-metabolic spectrum. (NephJC summary| FINE ARTS Freely Filtered Episode) Ongoing trials are FIND CKD (Heerspink et al, NDT 2024) which studied ns-MRAs’ role in non-diabetic CKD, and FINE-ONE (Heerspink et al, Diabetes research and Clinical Practice 2023) in type 1 DM.

Before slowly progressing to some conclusion, worth mentioning, mirroring the high CV risk in CKD, in patients ≥ 50 years, not needing RRT (1A), the guideline recommends statin or statin/ezetimibe combination initiation. No specific doses or targets are recommended in the CKD population.

KDIGO CKD 2024 is precise and thorough, leaving no CKD stone unturned. It critically dissects and reevaluates the evidence, showing a willingness to recalibrate when needed- even if it means downgrading once-firm recommendations to mere practice points. Take for instance, the 2012 2A recommendations for oral bicarbonate supplementation when serum bicarbonate drops below 22 mmo/L, now tempered to a more cautious approach. Nephrology learned to not just settle for what’s available, it has grown unrelenting selective, sharpening the focus on quality evidence underpinning clinical decisions. Looking ahead, with ongoing trials and the dynamic research landscape, the next KDIGO CKD guideline update should arrive far sooner than a decade.

5. Xenotransplantation

Again, you say? After 2021 (6th spot), and 2022 (4th spot) - xeno is back at Top Stories. The nephrology crowd seems to like this story of hope and technology and breakthroughs. Is there substance beyond the hype and the hope? In 2022, we said, ‘(this) is the main shortcoming or limitation of these studies - the model itself (brain dead decedents) and the short follow up. Are we ready for human trials?’. The year 2024 showed us that we were, indeed, ready for human trials. Multiple N of 1 trials, that is. Rick Slayman (March 21, 2024) and Towana Looney (November 24, 2024) were the first two humans to receive a pig kidney successfully, in Boston, and NY respectively. Sadly Rick Slayman passed away on May 11 2024, but Towana Looney is doing well at the time of this writing. Given the nature of the field, we do not know much of the details of the events this year, the presenter requested to take no photos or post on social media but there are things we can speculate as the narrative evolves.

CRISPR and related advances allowed the development of these porcine lineages which have spliced out and splice in the alpha-gal, porcine endogenous retroviruses [PERV] and the differences in major histocompatibility antigens aspects. But there seem to be two competing companies in the running here: Revivicor (now United Therapeutics, Maryland) and eGenesis (Cambridge, MA) which have slightly (or quite) different models. E.g. the Revivicor model is that of a UThymoKidney which has a thymic extract from the pig is implanted under the renal capsule a few weeks prior to implantation. Also different are the teams involved. While the first couple of transplants into brain dead decedents (the Parsons model, named after the late, first recipient) happened in UAB in Alabama and NYU in NY both from Revivicor, the Boston group (eGenesis) leapfrogged in March with the first human transplant in March. The Boston group is led by Leo Riella, with Tatsuo Kawai, and Nahel Elias. At NYU we have the larger-than-life Robert Montgomery, and they have now lured Jayme Locke from UAB (who performed the UAB transplant discussed on NephJC). This seems like a race - in terms of academia, personalities, and corporate interests. With N of 1 transplants, it is difficult to see which of these two competitors will win - but we do hope humanity (and kidney disease sufferers in particular) will come out ahead. Of course, in this race, the cardiologists did race ahead (sigh) with David Bennett Sr. receiving the first pig heart at the University of Maryland on Jan 7 2022. Hyperacute rejection was successfully avoided, though the patient did pass away of diastolic heart failure on day 47 (Mohiuddin et al Lancet 2023).

Beyond race and competition, its worthwhile to ponder if society is ready for pig kidneys. Ethical issues remain an important consideration (discussed nicely in Cooper et al, JASN 2020) especially around who should qualify (or risk) for these. Presently, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration is granting emergency approval for these through its single patient investigational new drug (IND) “compassionate use" pathway. Lastly - what will be the cost of these xenotransplants? Surely Revivicor and eGenesis are not doing these from the goodness of their heart (or kidneys). Beyond genetic engineering, the cost of maintaining the pristine environment in the pig farms is extraordinary. So are the costs of the expensive monoclonal antibodies that are still needed despite the genetic legerdemain conjured to make this possible. Though it often feels like change happens very slowly, and then suddenly, we may not be in the ‘suddenly’ curve of xenotransplantation yet. At least as far as its use beyond curious case reports to widespread implementation is concerned.

6. Microvascular inflammation increases risk of graft loss - in all of its forms

By Tiffany Caza

Antibody-mediated rejection (AMR) is associated with poor allograft outcomes, with reduced overall allograft survival and an increased risk of graft loss (Loupy et al, NEJM 2013). The characteristic triad of findings in AMR consists of presence of donor specific antibodies (DSAs), and presence of microvascular inflammation (MVI) and C4d deposition along peritubular capillaries on a kidney biopsy. MVI is the characteristic histologic lesion of AMR (Loupy et al, NEJM 2018) and includes glomerulitis (infiltration of mononuclear cells within glomerular capillaries) and peritubular capillaritis (presence of inflammatory cells within the peritubular capillaries. A challenge exists when there is MVI without DSAs and/or without C4d staining along peritubular capillaries. When evaluating transcriptomic profiles of rejection, MVI is a requirement for an AMR signature (Harmacek et al, AJT 2024), but it is unclear whether ALL cases of MVI represent rejection.

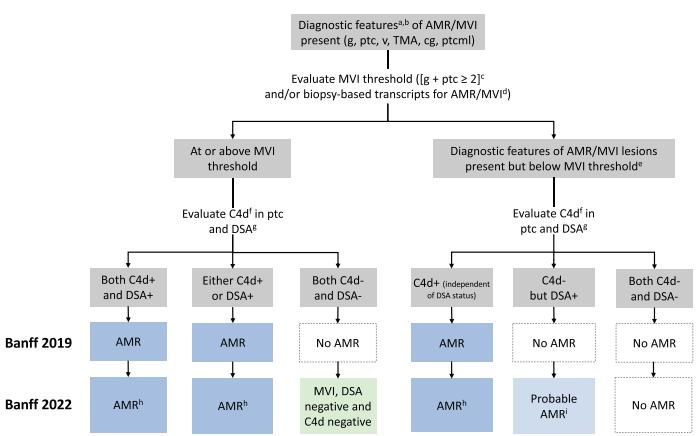

The 2022 Banff Classification of Allograft Rejection (Naesens et al, AJT 2024) created two new categories as guidance for further study of MVI in all of its forms and was a major change from the previous 2019 classification. MVI on kidney biopsies can now be classified into three categories: 1) AMR when MVI is accompanied by C4d staining along >10% of peritubular capillaries; 2) Probable AMR when MVI is present without C4d staining in a patient with positive DSAs; and 3) MVI, DSA negative, and C4d negative. This subdivision enables studies of the clinical significance of each scenario to inform outcomes.

Figure 1. Banff 2022 Classification of AMR and MVI subcategories. New categories from the Banff 2019 Classification include ‘Probable AMR’ and ‘MVI, DSA negative, C4d negative’. The Banff working group included these categories to enable further studies and determine the clinical significance of these categories. Figure credit: Naesens M et al, 2024.

Here is what a representative biopsy would look like within these three categories. Knowledge of the DSA status is essential at the time of biopsy for an accurate classification, although results are often not available at the time of biopsy in practice.

Figure 2. Histopathology of these MVI subcategories, demonstrating glomerulitis (g) and peritubular capillaritis (ptc), as well as representative images of C4d staining. An MVI-threshold exists with g + ptc ≥ 2. This minimum threshold can include mild glomerulitis with mild peritubular capillaritis (g1 ptc 1), moderate glomerulitis alone (g2, 25-50% of glomeruli involved), or moderate peritubular capillaritis alone (ptc2, 5-9 cells/peritubular capillary). Knowledge of DSA status is required for classification, as probable AMR and MVI C4d neg/DSA neg have identical biopsy findings.

A recent study published in the New England Journal of Medicine (Sablik et al, NEJM 2024) examined the impact of each MVI category on graft survival, as well as later development of AMR or transplant glomerulopathy. This large retrospective study was a collaborative effort from the Paris Transplant Group with >30 participant centers who retrospectively evaluated and re-classified 16,293 kidney biopsies from 6,798 transplant recipients to the 2022 Banff Classification. These included both protocol and indication biopsies, with the majority “for-cause”. This re-classification resulted in many biopsies previously diagnosed as ‘negative for rejection’ now placed into categories of ‘probable AMR’ or ‘MVI, DSA negative, C4d negative’. A total of 18.2% of cases fell into these two new MVI categories. A computer-based Banff automation system (Yoo et al, Nat Med 2023 for details) was used to facilitate the task of re-scoring. In biopsies with MVI, 56.9% were cases of AMR, 26.8% were MVI C4d negative/DSA negative, and 16.3% fit the category of ‘probable AMR’.

Figure 3. Reclassification of Allograft Rejection-Related Diagnoses According to the 2022 Banff Classification (Figure credit: Sablik M et al, 2024).

At follow-up (mean follow-up 5.0 years), there was reduced graft survival in patients with MVI not meeting criteria for AMR compared to patients without rejection, an intermediate risk between AMR and non-rejection. In addition, patients with probable AMR and MVI C4d negative/DSA negative were more likely to develop AMR or transplant glomerulopathy compared to patients without rejection, which may underlie the risk of graft loss. Transplant glomerulopathy is a consequence of chronic endothelial injury and on biopsy demonstrates a membranoproliferative pattern of glomerular injury without immune complex deposition. Transplant glomerulopathy results in persistent proteinuria in transplant recipients and is associated in itself with an increased risk of graft failure (Senev et al, Kidney Int 2021).

Figure 4. Cases of MVI alone or probable AMR have a worse prognosis than biopsies that are negative for rejection and without MVI. Patients with MVI alone or probable AMR have an increased likelihood of development of AMR (A) and/or transplant glomerulopathy (B). Figure credit: Sablik M et al, 2024.

Further work is required to understand the pathogenesis underlying MVI in the absence of C4d and donor-specific antibodies to identify potential targets for therapy. Since the optimal treatment(s) are unknown for patients with MVI not meeting criteria for AMR, patients may have reduced response to standard AMR treatment. MVI alone may not always be antibody-mediated, but may represent NK cell-mediated ‘missing self’ or even be T-cell mediated rejection. While additional studies are needed to better understand MVI in patients not meeting criteria for AMR, it is critical to recognize MVI alone as a significant finding, and no longer consider these patients to be simply “without rejection”.

7. Hyponatremia correction meta-analysis

By Joel Topf

The dogma regarding the treatment of hyponatremia for decades has been slower is better. This has largely been supported by small case series showing an association between rapid correction of serum sodium and the devastating neurologic complication, central pontine myelinolysis (CPM). As a result, the mantra of chronic hyponatremia has been no matter how fast you are correcting the serum sodium, you should go slower. Then in 2023, two papers came out that disrupted this long held dogma. Seethapathy et al (NEJM Evidence 2023) looked at hyponatremia correction in some hospitals in Boston, while Kinoshita et al (J Crit Care 2023) looked at hyponatremia from 208 ICUs from across the US. Both studies found increased mortality with slow correction of hyponatremia (gospel shattered). This was even its own region from this year’s NephMadness.

Medicine had been so focused on CPM, that no other outcomes were even considered. Since then, there has been some pushback (Sterns and Rondon Kidney 360, 2024) to this idea, but the end of 2024 brings us another piece to the puzzle, an 11,000 patient meta-analysis by Ayus et al. (JAMA Internal Medicine, 2024). Ayus found that rapid correction was associated with 32 in-hospital deaths per 1000 treated patients compared with slow correction- and a whopping 221 fewer deaths compared to very slow correction! Is the speed of correction associative or causal with mortality? Almost certainly there is some confounding from diagnosis. Sophisticated attempts at adjusting for this fall short, but does this confounding account for all of the difference in the mortality rates? Might be time for a randomized trial. Hyponatremia is too common not to have reliable data.

8. Workforce woes in Adult and Pediatric Nephrology

Nephrology workforce concerns have been around since the beginning of the profession, but until this year it has never made it into the Top 10 Nephrology Stories list (unlike suPAR and IgA nephropathy that are perennially present). Why are nephrologists feeling that this topic is so important now? Why this year? Match results were stable-ish in overall numbers. Adult nephrology saw 362 positions filled compared to 291 in 2019. Pediatric nephrology saw 29 positions filled, up from 21 in 2015 but down from our peak of 51 in 2021. Doesn’t sound terrible until you realize that there are currently 28 pediatric nephrology positions currently listed on the ASPN marketplace, and this is only the tip of the iceberg. My two open positions are not listed there, for example (Hey you, call me…). We’ve heard all of the reasons that people aren’t choosing nephrology. Kidney physiology is hard. We don’t make enough money. Patients are too complicated. Not enough innovation. Too many night calls. Fellowship is too long. I don’t know the answer to recruiting more people to nephrology, but a lot of smart people are working on this. I DO know that I love my job and find meaning in patient care and research and the teaching that I do.

The best I can personally do is model this joy for those following behind, make the profession as welcoming a space for everyone as possible, and hope that there will be someone to take over my patients when I retire.

Like suPAR, I’m hoping this topic disappears from the top 10, never to be heard from again. Want to learn more about pediatric subspecialty shortages? Watch this YouTube from Dr. Bryan Carmody (the Sheriff of Sodium): Touching the Elephant: The Pediatric Subspecialty Shortage

9. ApoE in C3 glomerulonephropathy

By Tom Oates

In about 2013 I sat in a room in the Hammersmith Hospital whilst Terry Cook talked us through the highlights of the first C3 glomerulopathy (C3G) meeting held some months before. I think many of us nodded along thinking that Terry’s joke that there were more authors on the subsequent paper (Pickering et al, Kidney Int 2013) than patients with the disease, would mean we wouldn’t have to re-educate ourselves on the labyrinthine links between old fashioned MPGN, new fangled C3G, and everyone’s least memorable bit of basic biology (well, maybe after the coagulation cascade), the complement system.

From: Bomback A, et al. KI Reports, 2025.

How wrong we were.

Since then, knowledge in this area has exploded. It is well reviewed here (Smith et al, Nat Rev Nephrol 2019), and extremely reductively summarised as there being two major subgroups of C3G - dense deposit disease (DDD) and C3GN. Dysregulation of the alternative pathway of complement is key to both and disease is often driven by autoantibodies that target C3 and C5 convertases.

From: Rifkin B, et al. KI Reports Community, 2023.

We are looking at this in “NephJC Top Stories”, because in March 2024 a paper was published showing that apolipoprotein E (ApoE) is a major component of the dense deposits seen histologically in DDD, and that DDD enriches terminal pathway complement proteins (Madden et al Kidney Int 2024 | NephJC Summary).

To me this is interesting for three reasons:

Diagnosis - staining biopsy tissue for ApoE may simplify diagnosis of DDD

Disease mechanism - the authors suggest that dense deposits may form as ApoE binds to proteoglycans in the GBM and scavenges C5-9, particularly in the face of increased complement activity

Treatment - are terminal pathway treatments such as C5 inhibitors going to evolve into key tools for DDD in particular?

I look forward to seeing how rapidly these three possibilities evolve in clinical practice.

10. Healthcare Cyberattacks

By Joel Topf

The most devastating electronic records hack occurred in February of 2024 when Change Healthcare was breached. Change Healthcare (a division of United Healthcare)is the largest U.S. billing and payment system in healthcare and the cyber attack disrupted payment to thousands of providers. The service disruption took months to unravel despite United Healthcare paying the $22 million ransom to the hackers. There is a lot of money in healthcare, and it will continue to attract criminals, hacktivists and bad actors both foreign and domestic.

Just as the Change Healthcare debacle was getting straightened out, the Ascension Hospital Systems was attacked resulting in a system-wide disruption of the electronic health system in all 140 hospitals they operate nationwide. My hospital was included in the outage and the 47 days of computerless medicine were terrible (NYTimes). Don’t believe me (or the paper of record)? Take a look at McGlave et al’s study (SSRN 2024) on hospital outcomes following ransomware attacks... they are not good. Let’s face it, none of us love EHRs, but they have become an integral and ubiquitous tool in the practice of medicine.

Then in July, CrowdStrike, a cybersecurity firm, tripped over its own feet and inadvertently caused the largest global computer outage ever. Ironically this occurred due to a faulty update, which was supposed to protect computers from cybercriminals. Oops. Unsurprisingly, many hospitals got caught in the chaos. (HealthcareDive)

These headlines don’t tell the whole story. In 2024 there were 677 major health data breaches affecting more than 182.4 million people in 2024. (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office for Civil Rights Link) We rely on computers to deliver care and they are vulnerable due to the complexity and need for integration in medicine and other fields. This is still a growing problem and needs to be taken seriously. Although it is not possible to make any system “hack proof” and simultaneously freely accessible, we all have a role in protecting sensitive information. The worst may be yet to come.