#NephJC Chat

Tuesday Dec 20th 9 pm Eastern

Wednesday Dec 21st 9 pm IST

Lancet 2022 Nov 12;400(10364):1693-1703. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01805-0. Epub 2022 Nov 4.

Personalised cooler dialysate for patients receiving maintenance haemodialysis (MyTEMP): a pragmatic, cluster-randomised trial

PMID: 36343653

Introduction

As nephrologists, we are well aware of the sad statistic that the median lifespan for our dialysis-dependent patients is 47 months and that cardiovascular death accounts for over half of these deaths - even after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic (United States Renal Data System | USRDS | NIDDK, n.d.). It is believed that intradialytic hypotension contributes to cardiovascular risk in our patients (Palmer & Henrich, JASN 2008). While cooler dialysate is used when dialysis patients develop intradialytic hypotension, no large scale RCT has tested the impact of cooler dialysate and cardiovascular outcomes.

Why cool the dialysate in the first place? Cooler temperature causes vasoconstriction, which raises blood pressure. The proposed mechanism for cool dialysate relies upon improved hemodynamic stability with lower body temperatures. Hemodynamic stress from dialysis is proposed to cause subclinical ischemic injury to both the heart and brain (Breidthardt & McIntyre, Rev Cardiovasc Med 2011). From the patient perspective, decreasing rates of intradialytic hypotension is important to reduce discomfort associated with hypotensive episodes. A systematic review in 2016 (Mustafa et al, CJASN 2016) also concluded that cooler dialysate may prevent intradialytic hypotension though noted the potential for significant bias in the preceding studies, particularly due to small size and short duration of follow-up. Despite these concerns, a reduction of 70% in intradialytic hypotension was found with cooler dialysate as was a decrease in the drop in pre-dialysis minus nadir intradialytic systolic blood pressure by about 10 mmHg.

Thus, MyTEMP was designed to provide the first large scale, randomized trial to evaluate the effect of the system-delivery of cooler dialysate on cardiovascular outcomes over an extended period of time (Al-Jaishi et al, Can J KHD 2020).

The Study

Methods

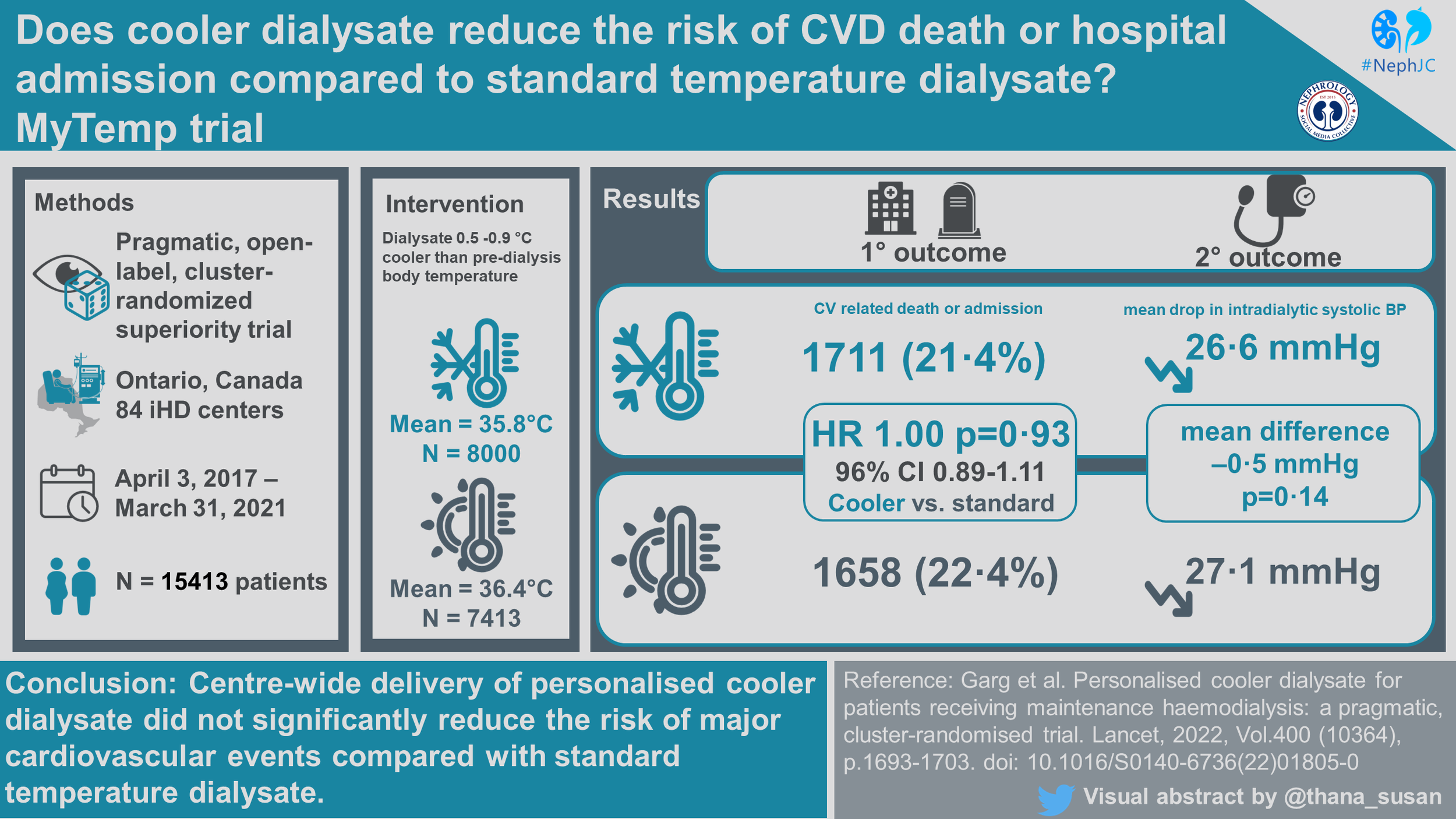

MyTEMP was a pragmatic, two-arm, parallel-group, registry-based, open-label, cluster-randomized superiority trial. It sought to determine whether a center-wide policy of personalized cooler dialysate at maintenance hemodialysis centers reduced the risk of cardiovascular-related death or hospital admission with myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke or congestive heart failure. For more on pragmatic cluster design, check out the NephTrials blog posts from Manasi.

As a pragmatic trial, all centers in Ontario, Canada with more than 15 patients treated per week were eligible. 84 of the 97 eligible centers were enrolled in the study. The authors used existing provincial databases for data collection. Patients’ temperatures and blood pressures were not routinely recorded in these databases, necessitating the independent collection of patient temperature and blood pressure. This was performed by randomly sampling 15 dialysis treatments at each center on a single day each month for later analysis.

Table 2 from Al-Jaishi et al, Can J KHD

Study Population

Inclusion Criteria

Center-specific

Location in Ontario, Canada

Delivery of maintenance hemodialysis to at least 15 patients weekly

Medical director agreement to delivery of randomly assigned intervention

Patient-specific

Receipt of dialysis at a participating center as of April 3, 2017 or during the following 4-year trial period

Duration of dialysis for more than 90 days

Adults >18 years old

Exclusion Criteria

Patients opting out of the intervention (these received the other intervention or control, but were still included in the outcomes and ITT analysis)

Intervention

The intervention in the MyTEMP trial was the delivery of hemodialysis center-wide personalized cooler dialysate. The 84 enrolled centers were randomized to either personalized cooler dialysate or standard temperature dialysate. Randomization occurred using a randomized allocation scheme to select 100,000 schemes with a good balance of set baseline characteristics, defined as 10% between-group standardized difference on constrained variables. A single randomization scheme was selected from among these by blinded investigators. Patients were unblinded and allowed to opt out of their assigned treatment group if desired.

Nurses in the personalized cooler dialysate centers set the dialysate temperature to 0.5℃ to 0.9℃ below the patient's body temperature for each haemodialysis treatment. A lower limit was set at 35.5℃ and as high as 36.5℃.

Nurses in the standard temperature dialysate group set the dialysate temperature to 36.5℃ for all patients and treatments.

Trial endpoints

Primary endpoint

A composite of cardiovascular-related death or hospital admission with a major cardiovascular event, including: myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, or congestive heart failure.

Secondary endpoints

The mean drop in intradialytic systolic blood pressure, defined as the difference in pre-dialysis systolic blood pressure and the lowest achieved systolic blood pressure during dialysis

Composite of all-cause mortality or cardiovascular-related hospitalizations

All-cause mortality

Individual components of the primary outcome

All-cause emergency room visits and all-cause hospital admissions

Hospital encounter with lower limb amputation

Hospital encounter with a major fall or fracture

18 patient-reported symptoms, including self-rated health, headache, muscle cramps, feeling cold on dialysis in a subset of patients from 10 (of 84) trial centers in 2019

Statistical Analysis

In this pre-specified analysis, the authors used an intention-to-treat approach, and included all patients who entered the trial, regardless of later transitions in dialysis care, transplantation, or non-adherence. A multi-variable generalized estimating equation was used to assess the primary outcome in order to account for the clustering of patient outcomes within centers and competing risks of non-cardiovascular death. For secondary outcomes, an unadjusted linear mixed model on the cluster-period summaries was used to account for repeated measures at the cluster level over time. To determine the best model for correlation of data over time, several models were analyzed (unstructured, compound symmetry, variance components, auto-regressive) with final model, a categorical fixed-period variable and autoregressive covariance structure, selected by blinded independent lead statistician based on (a) rule of parsimony (b) overall meaning for trial design and data collection methods and (c) model fit statistics.

The power calculations were based on a comparison of hazard rates accounting for clustering. The trial had an 80% power to detect a hazard ratio of 0.80; and 84% power to detect a 4 mmHg between group difference in BP.

Funding

The trial was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, Ontario Renal Network, Ontario Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research Support Unit, Dialysis Clinic, Inc., ICES, Lawson Health Research Institute and Western University. All sources had no role in any part of the trial design, data collection and analysis or writing of the report.

Results

Study Population

Eighty-four (of 92 eligible dialysis centers in Ontario) were randomized to either personalized cooler dialysate (n=42) or standard temperature dialysate (n=42), which encompassed an estimated 96% of all patients receiving dialysis in Ontario at that time. Over the 4 year trial period (April 3, 2017 to March 31, 2021), a total of 15413 patients were included, 8000 to personalized cooler dialysate and 7413 to standard temperature. Median follow-up was 1.8 years, and it was calculated that 80% of total patient-years of follow-up occurred at the patient’s index center (or center randomized to the same intervention). As expected, some patients (~ 7.5%) underwent a kidney transplant, and others (~ 5%) switched to a home dialysis modality.

Figure 1 from MyTEMP writing committee, Lancet 2022

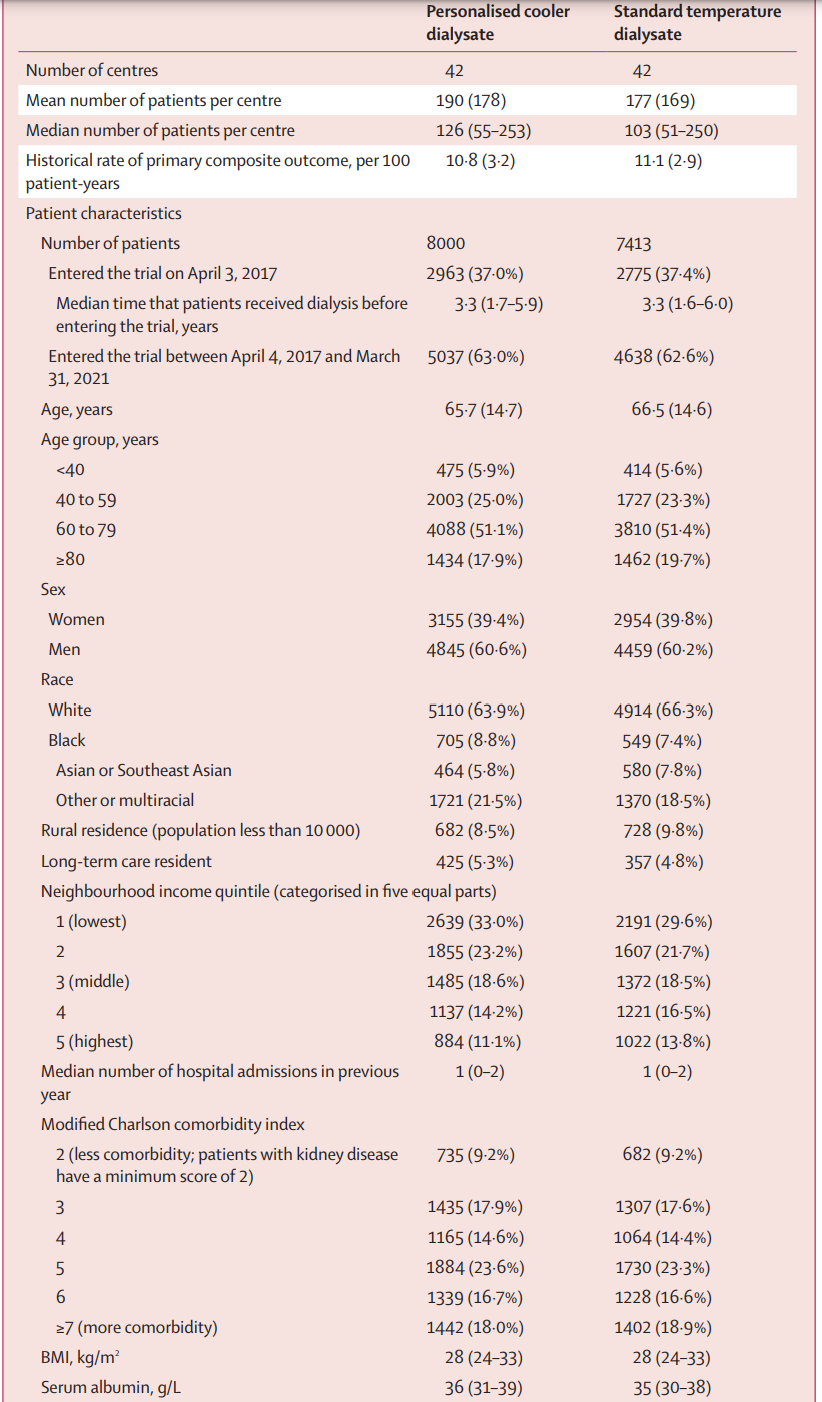

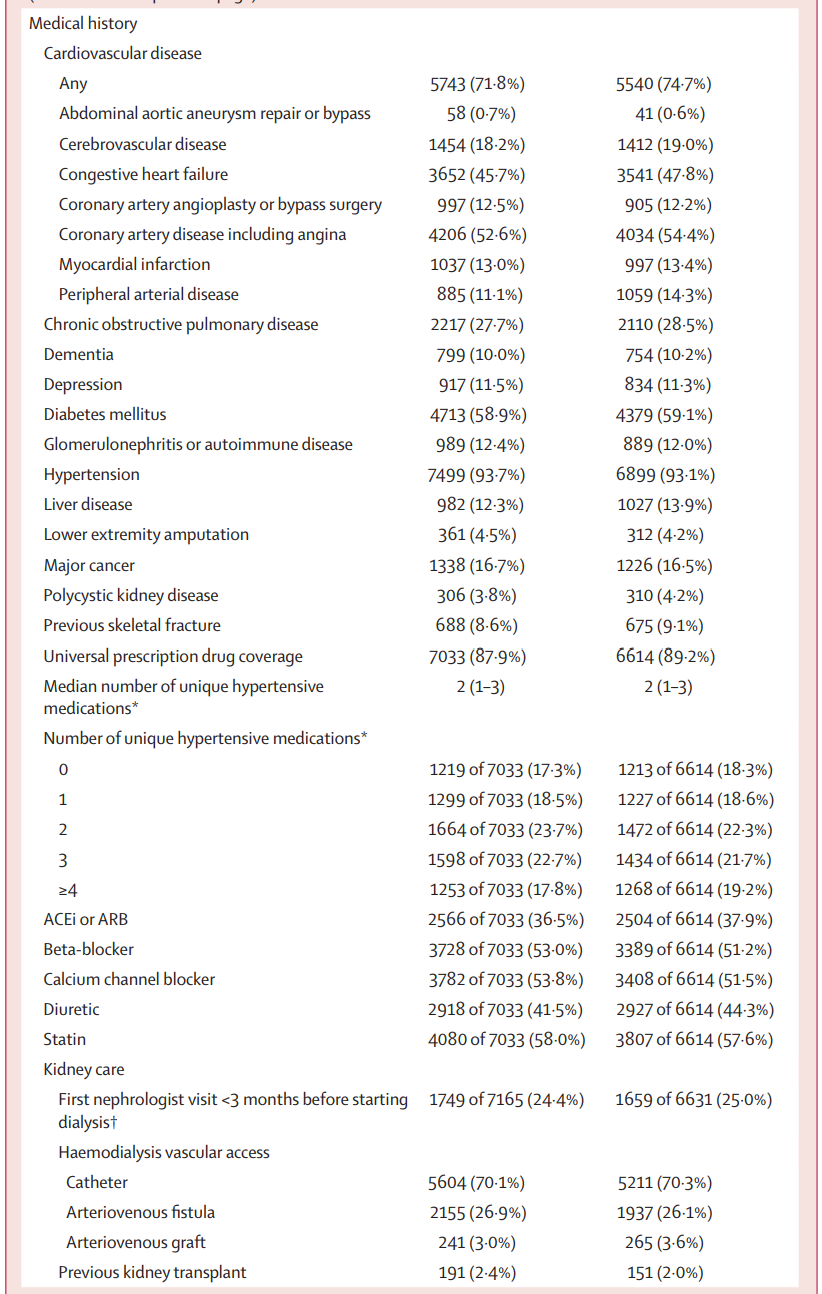

Table 1 is shown below. The median number of patients per center was about 180, and patients had had a median dialysis vintage of 3.3 years before entering the trial. The median age was ~ 66 years, with 60% men. About 65% were White, ~ 8% Black and ~ 6% Asian. About 5% were residents of long term care homes (i.e. nursing homes or skilled nursing facilities). About ~ 60% had DM, ~ 70% had prior cardiovascular disease, and ~70% received hemodialysis with a central line.

Table 1 from MyTEMP writing committee, Lancet 2022

Separation of Groups

Statistically different mean dialysate temperatures were achieved between the personalized cooler dialysate group (mean=35.8℃) and the standard dialysate group (mean=36.4℃) (based on the 15 treatments per center data collected each month - not all treatments/all patients). The mean between group difference was -0.61℃ (95% CI -0.65 to -0.58) with an average programmed dialysate temperature 0.40℃ below pre-dialysis body temperature and 0.14℃ above pre-dialysis body temperature in the personalized cooler and standard temperature groups respectively. Note that the body temperature of patients was measured according to each center’s routine standard of care and not the same method everywhere.

Figure 2 from MyTemp writing committee, Lancet 2022

Primary Outcome

There was no difference in the composite of cardiovascular outcomes between treatment groups. The primary outcome occurred in 21.4% and 22.4% of patients in the personalized cooler dialysate group and standard temperature dialysate group respectively, with an adjusted hazard ratio of 1.00 (CI 0.89 to 1.11, p=0.93).

Figure 3 from MyTEMP writing committee, Lancet 2022

Secondary Outcomes

There was no difference in the mean drop in intradialytic systolic blood pressure between groups with a 26.6 mmHg fall in blood pressure in the personalized cooler dialysate group and a 27.1 mmHg fall in blood pressure in the standard temperature group with a mean difference of 0.5 mmHg (99% CI -1.4 to 0.4, p=0.14). Again, this does not include all patients, but a random sample of 15 treatments per center per month.

Figure 4 from MyTemp writing committee, Lancet 2022

The authors also examined 5 definitions of intradialytic hypotension, with definitions summarized in the results table below. Again, no differences were seen between groups. Interestingly, the rates vary from ~ 10 to 42% based on the definition used.

Table S4 in the supplementary material for MyTemp writing committee, Lancet 2022

Similarly, in the additional pre-specified secondary analyses, no differences between groups were seen. This included individual components of the primary composite cardiovascular outcome, all-cause mortality or a cardiovascular-related hospital admission, all-cause mortality in isolation and non-cardiovascular mortality.

Table 2 from MyTEMP writing committee, Lancet 2022

Subgroup Analysis

The pre-specified and post-hoc subgroup analyses also showed no difference between personalized cooler dialysate and standard temperature dialysate across all subgroups, both pre-specified and on post-hoc analysis.

Figure S2 from MyTEMP writing committee, Lancet 2022

Patient-reported Symptoms

The single finding with statistical difference between the personalized cool dialysate and standard temperature dialysate groups in the MyTEMP trial was in patient-reported symptoms. Patients in the personalized cooler dialysate group were more likely to report feeling uncomfortably cold on dialysis with a relative risk of 1.6 and 99% confidence interval 1.1-2.5. Patient-reported scores for “feeling cold on dialysis” during the past week on a 0-10 scale from zero, “not at all [bothered]” to 10, “worst possible symptom.” This was not based on the entire population, but from a cross-sectional survey of 10 (of 84) centers in 2019.

Discussion

The concept that dialysis ‘default settings’ can be tweaked to lead to unit wide improvements is attractive, and has been investigated for every aspect of the dialysis prescription. In this study, the adoption of center-wide policy for personalized cooler dialysate versus a standard dialysate temperature of 36.5℃ did not significantly reduce the risk of their primary outcome, a composite of cardiovascular-related deaths or hospital admissions. The results of this trial are discordant with several prior studies suggesting lower temperature dialysate may reduce the rate of intradialytic hypotension. As summarized by Mustafa et al in 2016, most existing trials suffered from small sample size, a loss to follow-up and a lack of appropriate blinding leading to decreased confidence in the results of these prior trials.

The authors hypothesized that a personalized approach to dialysate temperature would be better tolerated by the patients as prior trials showed an improvement in patient energy (Ayoub et al, NDT 2004). Those on the personalized cooler dialysate, however, reported feeling more uncomfortable than their peers on the standard temperature dialysate. While the unblinding of patients in MyTEMP may have impacted patient responses, other trials have reported similar uncomfortable cold feelings (Mustafa et al, CJASN 2016).

Strengths

This was an exceptionally designed and completed clinical trial for which the authors should be congratulated. The trial’s pragmatic nature resulted in the ability to be the largest ever trial in hemodialysis patients and directly test patients in a setting with realistic implementation. Furthermore, the study design resulted in less than 2% of patients being lost to follow-up, decreasing the risk of bias. Additional strengths included the relatively low cost given the trial’s integration into the existing healthcare system. A prior study to understand barriers to implementation and provide support to nursing prior to study initiation was helpful in the conduct of this trial (Presseau et al. Trials, 2017).

Limitations

There were several limitations to this study, most notably involving the data collection for temperature and blood pressure measurements. Given the lack of inclusion of this data on the provincial data records available, the investigators collected this information from 15 random and de-identified sessions at each dialysis center on a monthly basis, capturing just 1% of all dialysis treatments. Likewise, data on alternative measures to treat intradialytic hypotension were not assessed which may have confounded results. Due to the enormous size of this study, collection of this information would have been labor intensive and this was a pragmatic decision.

Measurement of patient body temperature was not standardized and was according to each center’s standard of care - nor was there any analysis on the accuracy of this measurement. Given the protocol for the personalized cooler dialysate group adjusted the dialysate temperature based on this number, it is unfortunate this piece is missing.

Additionally, the patients’ lack of blinding may have biased their self-reported survey results, especially given the lack of validity data presented for their scale. These surveys were also collected from one cross sectional survey conducted midway through the trial in 10 centers only.

The authors chose the standard dialysate temperature of 36.5℃ given hemodialysis centers in Ontario most commonly use 36.5℃. Extrapolation of these results in the US, where the standard dialysate is 37℃, should be made cautiously, as many of the preliminary small trials used a comparator arm of 37℃ dialysate.

For the individual patient

Despite the negative results of this trial, we should consider other potential benefits of cooler dialysate. A smaller 73-patient RCT assessed the impact of cooler dialysate on cognitive functioning as assessed by diffusion tensor MRI changes to brain white matter (Eldehni et al, JASN 2015). Among incident (within 6 months) hemodialysis patients who were dialyzed at 0.5℃ below core body temperature, there were no white matter structural abnormalities at one year compared to those that underwent hemodialysis at 37℃. The same group also reported a slowing in the rate of progression of HD-associated cardiomyopathy as measured by a reduction in the volume of LV mass (Odudu et al, CJASN 2015). While the purported mechanism of protection for patients is similar to that assessed by MyTEMP, namely hemodynamic stability, MyTEMP did not assess long term cognitive changes or cardiac remodeling with imaging modalities. Unlike these trials also, MyTEMP included a mix of incident and prevalent patients. Beyond hemodynamics, van der Sande and colleagues, assessed energy transfer between patient and circuit in cool (35.5℃) and standard (37.5℃) dialysate. In their 9 person trial, cool dialysate promoted greater patient energy loss, though implications of this have yet to be further investigated (Van der Sande et al, AJKD 1999).

As these interventions were at a center level protocol, the results cannot be extrapolated to individual patients with documented intradialytic hypotension. Smaller patient level trials show probable improvement in intradialytic hypotension (Mustafa et al, CJASN 2016), and current practice guidelines (Kooman et al, NDT 2005, EBPG) recommend cooler dialysate as a first-line treatment to treat intradialytic hypotension. The results do not suggest abandonment of cool dialysate for treatment of documented intradialytic hypotension, but may warrant discontinuation as a preventative strategy for the entire unit. However, the bar for using cooler dialysate even for the individual patient should be higher, with more evidence based interventions tried first.

Finally, what additional questions should we be answering using a similar design? Future cluster randomized dialysis center trials may shed light on topics currently lacking clarity in the growing hemodialysis population. Ongoing cluster RCTs include RESOLVE, DialMAG, and many more. Optimized catheter lock protocols or standardization of exit site care offer tantalizing opportunities for investigation by registry based RCTs.

Conclusions

Based on the results of the MyTEMP trial, there is no clear cardiovascular benefit from implementation of a dialysis center based personalized cooler dialysate temperature protocol compared with a standard temperature dialysate, set at 36.5℃, suggesting center-wide cooler dialysate policies should not be adopted.

Summary prepared by Dana Larsen, MD

Nephrologist, University of California, San Francisco

NSMC Intern 2022

Reviewed by Srikanth Bathini, Jamie Willows, Swapnil Hiremath, Joel Topƒ